Collins v Willock 1984

advertisement

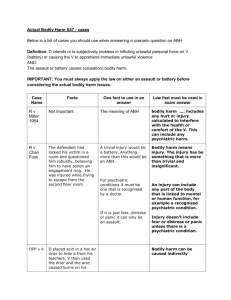

G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] NON FATAL OFFENCES AGAINST THE PERSON. For this topic you need to be able to explain the following terms, with cases and limitations on their use: Common assault Battery Assault occasioning actual bodily harm Malicious wounding and inflicting grievous bodily harm Wounding or causing grievous bodily harm with intent. This means you need to know the actus reus and the mens rea requirements for each, their maximum sentences and what sort of things they cover. Easy huh? You will also need to be able to evaluate the reform proposals for this area of law, and be able to criticise the state of the current law. End of Unit Question: Ian is at a party and is very drunk. he picks up a glass of beer and tries to throw the contents over Jiao, his former girlfriend. The glass slips from his hand as he is throwing it and strikes Jiao, cutting her cheek. Jiao's new boyfriend, Kapil, calls Ian a 'drunken idiot'. Angered by this, Ian lurches at Kapil but stumbles over a chair breaking one of the chair legs. He picks up the broken leg and, believing Kapil is about to punch him, tries to hit Kapil over the head with it but only succeeds in hitting Jiao. Jiao is taken to hospital where x-rays reveal she has a fractured skull. Discuss Ian's potential criminal liability including any defences he may have available to him. [OCR, Jun07] 1 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] ASSAULT AND BATTERY Well, firstly, these are two separate offences. They are common law offences, which means that their definitions come from the courts, but they are charged under s.39 Criminal Justice Act 1998. This states that on conviction, D may be sentenced to up to 6 months in custody or a fine of £5000. These offences will be heard in the court. Please note: It is perfectly possible for D to be charged with both, or just one offence. Read the three situations below, and use them to work out what the difference between the two offences is. 1. Bob runs up to Val and screams, “I’m going to hit you!”. Unfortunately, before he can hit her, he trips up. 2. Bob runs up to Val and screams, “I’m going to hit you!” and cuts her hair 3. Bob sneaks up on Val from behind and hits her over the head. ASSAULT. This is also known as ‘technical’ or ‘psychic’ assault. Why? Well, you don’t have to actually touch the victim. What is important here is that the victim thought that they would be assaulted (or ‘apprehended’) Definition: “an act by which a person intentionally or recklessly causes another to apprehend immediate and unlawful violence.” R v Venna So, what does this mean? Apprehend? This does not mean fear. Why not? . What it means is that V should be aware that something violent may happen. The threat of violence is enough and it does not have to be carried out Immediate? For this, we need to look at two different cases. The word immediate has been given quite a wide interpretation by the courts, and is now taken to really mean “imminent”. This means that the violence doesn’t have to take place then and there, but may take place at some time in the near future. The threat must also be of violence. 2 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] Smith v Chief Superintendent of Woking Police Station (1983) Facts: Ratio: Immediate means imminent, and not necessarily instantaneous. It is enough that there is “an apprehension of what D might do next” Kerr LJ. R v Constanza 1997 CA Facts: Ratio: The assault arises from the fact that V does not know what is coming next. How apprehension arose in V is unimportant. The only important thing is that V apprehended the violence occurring “at some time not excluding the immediate future.” Schiemann LJ Would the court have handed down the same result if D had not lived near to V? Why/why not? Unlawful? Do I really need to explain this? If the action is lawful, there is no assault. E.g. a stop and search. Are words enough? Well, the short answer is yes! In fact, a gesture is sufficient… Just think, if someone raises a bat to you, you will feel threatened even though they might not have said anything. This however has not always been the case. [Meade and Belt 1823] Originally it was thought that only if there was some kind of physical threat as well, would D be convicted. You should also remember that D can negate the assault through the words that he says. Generally speaking, if the words show that no violence will be taking place, or it is impossible, then there can be no offence of assault. It is the circumstances of the threat which are all important. The classic example is the idiot who yells out of a moving train, “I’m gonna beat you up!” Why is there no assault in this situation? 3 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] TASK: compare the facts in the following two cases. Why was the decision in Light so different to the earlier? Why the different decision? Tuberville v Savage 1669 R v Light 1857 Facts: D was arguing with V, put his hand on his sword and said, “If it were no assize time, I would not take such language from you.” Facts: D held the sword above his wife’s head and said, “Were it not for the bloody policeman outside, I would Split your head open.” R v Ireland 1997 this is a key case, and was the subject of a joint appeal with Burstow, which we will come back to later. Answer the following questions. 1. What had Ireland done? 2. What offence had he been charged with? 3.Why does Steyn argue that words (or gestures) are sufficient for assault? 4. How were the facts of Ireland not covered by the idea that words may be enough for assault? 5. What is the key ingredient in assessing whether silent phone calls constitute an assault? 6. What is the test that will be put before the jury? 4 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] 7. How does Lord Hope justify upholding the conviction? Consolidation Complete the following table for the AR and MR of assault. Give an example for each. Actus Reus Mens Rea BATTERY Battery differs from assault in that it requires an application of unlawful force to another person. This often charged with assault, and is also a summary offence attracting the same sentence [ ]. However, it is perfectly possible to convict D only of assault. If V is asleep or D creeps up on V unheard and then hit them, this is battery! Please also bear in mind that many situations where you might think that there was battery e.g. an overcrowed bus, are also said to be situations where there is ‘implied consent’. More about this later… So, what do we mean by ‘unlawful force’? Collins v Willock 1984 Facts: D was a police officer who tried to stop V leaving, as she thought she was a prostitute. V refused and walked off. D then took arm and V fought back , scratching the arm and being abusive. Ratio: “ it has long been established that any touching of another person, however slight, may amount to battery” Goff LJ Do you agree with this statement? What limitations do you think should be put on this offence? 5 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] Listen to the facts of R v Thomas (1985). Is this a realistic interpretation of the law? Why do you think that the judges allowed this? Does the touching have to be hostile? We would assume so, really, and the current state of the law seems to be yes, it should be hostile. Why? Well, keep a list of all the people you come into contact with in one day… how many of those situations could be described as ‘battery’? The current idea is that hostility is not enough on its own, but is very useful to the courts in deciding whether ‘new’ situations could be hostile situations [Lord Mustill in R v Brown 1993, approving Wilson and Pringle which is actually a civil case. Can it be done indirectly? Ooh, I like these easy questions! YES!!! V doesn’t have to have seen it coming. R v Martin 1881 Facts: Ratio: DPP v Khan (1990) otherwise known as the “look, I told you the school toilets were dangerous!” case. Facts Ratio: Listen to the facts of the following case. Which doctrine (rule) which we have come across earlier in the course is being illustrated here? Haystead v CC of Derbyshire 2000 Facts: Ratio: 6 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] There is one last case that I should mention here as well… Fagan v Metropolitan Police Commisioner 1983 . What does this illustrate about battery and the application of force? What about omissions? Usual rule: only if D had a duty, and then failed to act. There is no general liability for omissions. So, how do we know which duties are included. Ah! A little bit of revision. Below, list the duty situations the courts have acknowledged: Consolidation Actus Reus Mens Rea 7 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] ASSAULT OCCASIONING ACTUAL BODILY HARM Definition This is covered by s.47 Offences Against the Person Act 1861. The offence is committed when a person assaults another, thereby causing actual bodily harm, which is an either way offence and carries a maximum penalty on indictment of five years' imprisonment and/or an unlimited fine not exceeding the statutory maximum. So, what is the difference between this and common assault and battery? Well, really it is the level of harm done to V. Actual bodily? This is given its ordinary meaning and includes any hurt calculated to interfere with the health or comfort of the victim. It needs to be more than merely transient or trifling. In fact, according to Hobhouse LJ in R v Chan Fook 1994 as long as it “not so trivial as to be insignificant” that is sufficient. Donovan 1954 What if V just loses consciousness? Does it matter how long they lose consciousness for? R(T) v DPP 2003 Facts: Ratio: It even included hair! DPP v Smith 2006 “It is concerned with the victim”. Occasioning means nothing more than ‘causing’. Psyhcic injury? Mens rea? There is actually no reference in the section to MR. But the key element of the offence is the mens rea is that of . Mens Rea: , and therefore ; or Now, remember that there is no need for D to intend or be reckless as to whether ABH is actually caused. This means that they might not even see it coming and still be liable! What do I mean by this? Well.... 8 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] R v Roberts 1971 Facts: Ratio: The unlawful force used in trying to remove the coat was enough. V’s injuries were the “natural consequence” of D’s actions i.e. they could be reasonably foreseen. It was irrelevant that D neither intended the injury nor realised that there was a risk of injury. This was confirmed in R v Savage, Parmenter 1991 Facts: Ratio: Psychiatric Harm R v Chan-Fook 1994 approved of in R v Burstow 1997 Facts: Read the extract and answer the following questions: 1. What is the ‘body’ include? 2. What is excluded from psychiatric harm? 3. What evidence should the defendant advance? 4. Do they think there will be a lot of cases? 5. What is the outcome of the appeal? Do you agree? Why/why not? 9 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] MALICIOUS WOUNDING OR INFLICTING GBH Definition & sentences “Whosoever shall unlawfully and maliciously wound or inflict any grievous bodily harm upon any other person, either with or without a weapon or instruments shall be guilty of an offence and shall be liable to imprisonment for not more than five years. s.20 Offences Against The Person Act 1861 1. What is the mens rea? 2. What are the two types of actus reus which may be enough for the offence? 3. What is the sentence and how does this compare to a s.47 offence? Wound? Remember: this means a cut or break in the continuity of the skin. The cut has to go through all the layers of the skin. Now, if the assault causes a cut on the internal skin e.g. cheek, then that is sufficient. However if the assault only causes internal bleeding, then that is not enough for wounding. What if V suffers a broken bone. Is that sufficient for ‘wounding’? Wood 1830 JCC v Eisenhower 1983 Facts: Ratio: Meaning of GBH Remember, that the meaning of this is the same here, as for both s.18 and . What, though, does it mean? DPP v Smith 1961 says that GBH means “no more and no less than really serious harm” although that may not be life threatening. (helpful huh?). The CA modified this in R v Saunders 1985 saying that instructing the jury to consider whether the injuries were “serious” was sufficient. 10 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] So, what if V is particularly young or unhealthy? Can the jury bear that in mind in assessing the harm? R v Bollom 2004 Facts: Ratio: Biological GBH – see later What do we mean by the word ‘inflict’ This is very widely interpreted! Well, this was another thing that used to drive the courts mad. One of the main differences between s.20 and s.18 is the verb usage! Section 18 uses ‘cause’ and section 20 ‘inflicts’. What’s the difference? Well, before 1997 the idea was that ‘cause’ was wider as confirmed by the House of Lords as late as 1995. However, in that old case of Ireland & Burstow HL finally decided that the words may be interchangeable. R v Lewis 1974 Facts: Ratio: Psychiatric injury R v Burstow 1997 Facts: 1. Is an assault necessary for a conviction under s.20? 2. Can you inflict a psychiatric injury? 11 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] Thus, all that needs to be shown is that D’s actions led to the consequence of some GBH being suffered, and no technical assault needs to be suffered. Realistically all of this means that there is little difference between s.18 and s.20. Why might that be a problem? Maliciously (MR) The courts have said that maliciously actually means.... recklessly! The test followed is the subjective test laid out by R v Cunningham 1987: ; and So therefore, the mens rea for the section is either intention or subjective recklessness. It is enough that D foresaw some harm to some person, albeit of a minor character. R v Parmenter 1991 HL Facts: Ratio: 12 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] WOUNDING OR CAUSING GBH WITH INTENT. The definition & four crimes. Whosoever shall unlawfully and maliciously by any means whatsoever wound or cause any GBH to any person, or with intent to resist or prevent the lawful apprehension or detainer of any person shall be guilty of an offence and be liable on indictment for a sentence of up to and including life. s.18 Offences Against the Person Act 1861 Thus, there are four offences within the section: 1. 2. 3. 4. Mens Rea This is a crime of specific intent, which means it can be done directly or obliquely. It requires an intention to either: 1. Do some GBH; or 2. Resist or prevent the lawful apprehension or detainer of any person. Intent for GBH Well firstly, be careful: the courts have said that the word ‘maliciously’ adds nothing to the definition ( R v Mowatt 1968)!!! Recklessness is not enough. The test for oblique intention is the same as the test for oblique intent for murder. This means we need to look at some very familiar cases (remember all that stuff about foresight of consequences?)! Complete the following table with facts and tests: CASE FACTS TEST R v Moloney R v Nedrick R v Woolin 13 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] Preventing Arrest The level of intention is lower here. Yes, there must be an intent to resist arrest, but the prosecution must also prove that D was reckless as to whether their actions would cause any wound or injury. R v Morrison 1989 Facts: Ratio: Alternative convictions and the charging standards The jury may convict D of a lesser offence if all the elements (particularly the MR) are not proven beyond reasonable doubt, then they may pick the lesser. e.g. s.47 in a s.20 offence (R v Savage 1992) s.20 in a s.18 offence (R v Mondair 1995) Take care: a s.47 can not be replaced with a common assault or battery Why? J Types of Injuries and the Charging Standards. Because of all the problems in figuring out what to charge, the CPS has issued guidance on what should be charged when. IS task: Research the types of injuries which are commonly charged under each heading (five for each). Also, for each one identify aggravating factors in sentencing. Charge Common assault & battery Examples Aggravating factors s.47 Assault occasioning ABH s.20 Causing GBH or Wounding s.18 Inflicting GBH or Wounding 14 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] BIOLOGICAL GBH Can you inflict GBH biologically? Well, for years the courts said no. The problem is the meaning of the verb ‘inflict’. Oh yes, an English lesson!!! The traditional approach from the courts is that of Clarence 1888. This is the case of the husband who had gonorrhoea, slept with his wife (with her consent!) without telling her he was carrying the disease, and passed it on to her. He was convicted of GBH and assault occasioning ABH. However, his appeal was allowed. The reason was the narrower meaning of influence. The court said that it meant causing an assault to take place. In the meantime, Canada got fed up with this approach.... Cuerrier 1998 Facts: Ratio: Now, following the cases of Burstow & Ireland, inflict simply means to ‘cause’. How does this change it? R v Dica 2004 CA Facts: Ratio: Judge LJ “remove some outdated restriction against the successful prosecution of those who, knowing that they are suffering HIV or some other serious sexual disease, recklessly transmit it through consensual sexual intercourse and inflict GBH on a person from whom threat is concealed.” D’s conviction was overturned due to misdirection, and a retrial ordered. He was convicted and sentenced to 4 years. This was upheld in the later case of R v Konzami 2005 15 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] R v IRELAND; R v BURStOW [1997] 4 AER 225 Edited text [from elawstudent.com] SUMMARY Two appeals from conviction were considered together. The first appeal was by Burstow, a naval petty officer against dismissal of his appeal against conviction for inflicting grievous bodily harm contrary to s.20 Offences against the Person Act 1861 by stalking his victim. Burstow had stalked his victim and contended that the absence of direct or indirect physical violence could not amount to grievous bodily harm. The second appeal was by Ireland who appealed against dismissal of his appeal against conviction and sentence of three months’ imprisonment on three counts of assault occasioning actual bodily harm contrary to s.47 Offences against the Person Act 1861 by repeatedly making silent telephone calls accompanied by heavy breathing, to three women. Edited text IRELAND & ASSAULT LORD STEYN: My Lords, it is easy to understand the terrifying effect of a campaign of telephone calls at night by a silent caller to a woman living on her own. It would be natural for the victim to regard the calls as menacing. What may heighten her fear is that she will not know what the caller may do next. The spectre of the caller arriving at her doorstep bent on inflicting personal violence on her may come to dominate her thinking … That the criminal law should be able to deal with this problem, and so far as is practicable, afford effective protection to victims is self evident. … Was there an assault? It is now necessary to consider whether the making of silent telephone calls causing psychiatric injury is capable of constituting an assault [which] is an act causing the victim to apprehend an imminent application of force upon her … … Counsel argued that as a matter of law an assault can never be committed by words alone and therefore it cannot be committed by silence. The premise depends on the slenderest authority, namely, an observation by Holroyd J. to a jury that ‘no words or singing are equivalent to an assault’: Meade’s and Belt’s case 1 (1823) 1 Lew. C.C. 184. The proposition that a gesture may amount to an assault, but that words can never suffice, is unrealistic and indefensible. A thing said is also a thing done. There is no reason why something said should be incapable of causing an apprehension of immediate personal violence, e.g. a man accosting a woman in a dark alley saying ‘come with me or I will stab you.’ I would, therefore, reject the proposition that an assault can never be committed by words. 16 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] That brings me to the critical question whether a silent caller may be guilty of an assault. The answer to this question seems to me to be ‘yes, depending on the facts.’ It involves questions of fact within the province of the jury. After all, there is no reason why a telephone caller who says to a woman in a menacing way ‘I will be at your door in a minute or two’ may not be guilty of an assault if he causes his victim to apprehend immediate personal violence. Take now the case of the silent caller. He intends by his silence to cause fear and he is so understood. The victim is assailed by uncertainty about his intentions. Fear may dominate her emotions, and it may be the fear that the caller’s arrival at her door may be imminent. She may fear the possibility of immediate personal violence. As a matter of law the caller may be guilty of an assault: whether he is or not will depend on the circumstance and in particular on the impact of the caller’s potentially menacing call or calls on the victim. … [A] trial judge may, depending on the circumstances, put a common sense consideration before jury, namely what, if not the possibility of imminent personal violence, was the victim terrified about? I conclude that an assault may be committed in the particular factual circumstances which I have envisaged. For this reason I reject the submission that as a matter of law a silent telephone caller cannot ever be guilty of an [assault] … I would therefore dismiss the appeal of Ireland. LORD HOPE OF CRAIGHEAD: … [I]t is not true to say that mere words or gestures can never constitute an assault. It all depends on the circumstances. If the words or gestures are accompanied in their turn by gestures or by words which threaten immediate and unlawful violence, that will be sufficient for an assault. The words or gestures must be seen in their whole context. In this case the means which the appellant used to communicate with his victims was the telephone. While he remained silent, there can be no doubt that he was intentionally communicating with them as directly as if he was present with them in the same room. But whereas for him merely to remain silent with them in the same room, where they could see him and assess his demeanour, would have been unlikely to give rise to any feelings of apprehension on their part, his silence when using the telephone in calls made to them repeatedly was an act of an entirely different character. He was using his silence as a means of conveying a message to his victims. This was that he knew who and where they were, and that his purpose in making contact with them was as malicious as it was deliberate. In my opinion silent telephone calls of this nature are just as capable as words or gestures, said or made in the presence of the victim, of causing an apprehension of immediate and unlawful violence. BURSTOW & WHETHER AN ASSAULT IS REQUIRED UNDER SECTION 20 Counsel for Burstow then advanced a sustained argument that an assault is an ingredient of an offence under section 20. He referred your Lordships to cases which in my judgment simply do not yield what he sought to extract from them. In any event, the tour of the cases revealed conflicting dicta, no authority binding on the House of Lords, and no settled practice holding expressly that assault was an ingredient of section 20. And, needless to say, none of the cases focused on the infliction of psychiatric injury. In these circumstances I do not propose to embark on a general review of the cases cited … 17 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] Instead I turn to the words of the section. Counsel’s argument can only prevail if one may supplement the section by reading it as providing ‘inflict by assault any grievous bodily harm.’ Such an implication is, however, not necessary. On the contrary, section 20, like section 18, works perfectly satisfactorily without such an implication. I would reject this part of counsel’s argument. BURSTOW & THE MEANING OF ‘INFLICT’ IN SECTION 20 The appeal of Burstow lies in respect of his conviction under section 20. … Counsel laid stress on the difference between ‘causing’ grievous bodily harm in section 18 and ‘inflicting’ grievous bodily harm in section 20. Counsel argued that the difference in wording reveals a difference in legislative intent: inflict is a narrower concept than cause. This argument loses sight of the genesis of sections 18 and 20. In his commentary on the Act of 1861 Greaves, the draftsman, explained the position: The Criminal Law Consolidation and Amendment Acts, 2nd ed. (1862). He said (at pp. 34): ‘If any question should arise in which any comparison may be instituted between different sections of any one or several of these Acts, it must be carefully borne in mind in what manner these Acts were framed. None of them was re-written; on the contrary, each contains enactments taken from different Acts passed at different times and with different views, and frequently varying from each other in phraseology, and...these enactments, for the most part, stand in these Acts with little or no variation in their phraseology, and, consequently, their differences in that respect will be found generally to remain in these Acts. It follows, therefore, from hence, that any argument as to a difference in the intention of the legislature, which may be drawn from a difference in the terms of one clause from those in another, will be entitled to no weight in the construction of such clauses; for that argument can only apply with force where an Act is framed from beginning to end with one and the same view, and with the intention of making it thoroughly consistent throughout.’ The difference in language is therefore not a significant factor ... But counsel … submitted that it is inherent in the word ‘inflict’ that there must be a direct … application of force to the body [and there is] the troublesome authority of the decision Court for Crown Cases Reserved in Reg. v. Clarence (1888) 22 Q.B.D. 23 [in the Library]. At a time when the defendant knew that he was suffering from a venereal disease, and his wife was ignorant of his condition, he had sexual intercourse with her. He communicated the disease to her. The defendant was charged and convicted of inflicting grievous bodily harm under section 20. There was an appeal. By a majority of nine to four the court quashed the conviction. The case was complicated by an issue of consent. But it must be accepted that in a case where there was direct physical contact the majority ruled that the requirement of infliction was not satisfied. This decision has never been overruled. It assists counsel’s argument. But it seems to me that what detracts from the weight to be given to the dicta in Clarence is that none of the judges in that case had before them the possibility of the inflicting, or causing, of psychiatric injury. The criminal law has moved on in the light of a developing understanding of the link between the body and psychiatric injury. In my judgment Clarence no longer assists. The problem is one of construction. The question is whether as a matter of current usage the contextual interpretation of ‘inflict’ can embrace the idea of one person inflicting psychiatric injury on another. One can without straining the language in 18 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] any way answer that question in the affirmative. I am not saying that the words cause and inflict are exactly synonymous. They are not. What I am saying is that in the context of the Act of 1861 one can nowadays quite naturally speak of inflicting psychiatric injury. … 19 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] R v CHAN-FOOK [1994] 2 All ER 552 * from elawstudent.com HOBHOUSE LJ: … Actual bodily harm … are three words of the English language which require no elaboration and in the ordinary course should not receive any. The word ‘harm’ is a synonym for injury. The word ‘actual’ indicates that the injury (although there is no need for it to be permanent) should not be so trivial as to be wholly insignificant. The purpose of the definition in s.47 is to define an element of aggravation in the assault. It must be an assault which besides being an assault (or assault and battery) causes to the victim some injury. … No doubt what is intended by those who have used these words in the past is to indicate that some injury which otherwise might be regarded as wholly trivial is not to be so regarded because it has caused the victim pain. Similarly an injury can be caused to someone by injuring their health; an assault may have the consequence of infecting the victim with a disease or causing the victim to become ill. The injury may be internal and may not be accompanied by any external injury. A blow may leave no external mark but may cause the victim to lose consciousness .... The first question on the present appeal is whether the inclusion of the word ‘bodily’ in the phrase ‘actual bodily harm’ limits harm to harm to the skin, flesh and bones of the victim. Lynskey J rejected this submission. In our judgment he was right to do so. The body of the victim includes all parts of his body, including his organs, his nervous system and his brain. Bodily injury therefore may include injury to any of those parts of his body responsible for his mental and other faculties .... Accordingly the phrase ‘actual bodily harm’ is capable of including psychiatric injury. But it does not include mere emotions such as fear or distress or panic nor does it include, as such, states of mind that are not themselves evidence of some identifiable clinical condition. The phrase ‘state of mind’ is not a scientific one and should be avoided in considering whether or not a psychiatric injury has been caused; its use is likely to create in the minds of the jury the impression that something which is no more than a strong emotion, such as extreme fear or panic, can amount to actual bodily harm. It cannot. Similarly juries should not be directed that an assault which causes a hysterical and nervous condition is an assault occasioning actual bodily harm. Where there is evidence that the assault has caused some psychiatric injury, the jury should be directed that that injury is capable of amounting to actual bodily harm; otherwise there should be no reference to the mental state of the victim following the assault unless it be relevant to some other aspect of the case … It is also relevant to have in mind the relationship between the offence of aggravated assault comprised in s.47 and simple assault. The latter can include conduct which causes the victim to apprehend immediate and unlawful violence … To treat the victim’s fear of such unlawful violence, without more, as amounting to actual bodily harm would be to risk rendering the definition of the aggravated offence academic in many cases. In any case where psychiatric injury is relied upon as the basis for an allegation of bodily harm, and the matter has not been admitted by the defence, expert evidence should be called by the prosecution. It should not be left to be inferred by the jury from the general facts of the case. In the absence of appropriate expert evidence a question whether or not the assault 20 G144 Criminal Law A2 Law [OCR] occasioned psychiatric injury should not be left to the jury. Cases where it is necessary to allege that psychiatric injury has been caused by an assault will be very few and far between. Appeal allowed. Conviction quashed. 21