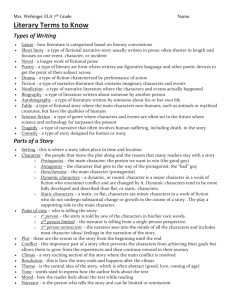

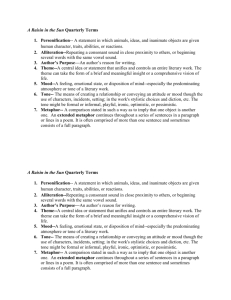

Literary Terms to be Studied/Learned by 11th Grade

advertisement

Literary Terms Defined Absurdist literature (literature of the absurd)—works that have in common the sense that the human condition is essentially absurd, and that this condition can be adequately represented only in works of literature that are themselves absurd. Often use black humor. Allegory—a narrative in which characters, actions, and setting are contrived by the author to make sense on the literal (or concrete) level while signifying a second (usually abstract) meaning to make a point about human nature. Allusion—a passing reference, without explicit identification, to a literary or historical place, or event, or to another literary work or passage. Bathos—when an author unintentionally makes a situation or character seem trivial or ridiculous by overworking a pathetic or passionate situation or character. See also pathos. Black humor—baleful, naïve, or inept characters in a fantastic or nightmarish modern world play out their roles in events which are often simultaneously comic, horrifying, and absurd. Characterization—the way an author establishes distinctive qualities (moral, intellectual, physical and emotional) of a person in a narrative. Indirect characterization—characterization by means of dialogue and/or what other characters say about the character Direct characterization—when the author directly informs the readers of the character’s qualities. Types of Characterization: Protagonist—the main character of a narrative, often its hero or heroine Antagonist—a character who is in real or imagined opposition to the protagonist (called a villain if evil) Antihero—a protagonist who has the opposite of most of the traditional attributes of a hero. He or she may be bewildered, ineffectual, deluded, or merely pathetic. Often what antiheroes learn, if they learn anything at all, is that the world isolates them in an existence devoid of God and absolute values. Yossarian from Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 is an example of an antihero. Round character—a full, complex, multi-dimensional character whose personality reveals some of the richness we are accustomed to observing in actual people Dynamic character—a character who undergoes a permanent change in morality in the story Flat character—a simple, one-dimensional, usually unchanging character who shows none of the human depth or complexity of a round character 1 Static character—a character who does not change throughout the work, and the reader’s knowledge of that character does not grow Stock Character—conventional characters who appear in numerous works, especially works of the same type, and behave in predictable ways. Examples include the cruel stepmother in fairy tales, or the hardboiled detective in mystery stories. These characters sometimes serve as a stereotype. Foil character—a character who parallels another major character and by sharp contrast, serves to stress and highlight the distinctive qualities of both Persona—the fictional mask or identity that a narrator uses to tell a story Climax— The second part is the climax, the moment of greatest emotional tension in a narrative, usually marking a turning point in the plot at which the rising action reverses to become the falling action Complication—the point at which the conflict (internal, external, or some combination thereof is introduced) Conflict—the struggle within the plot between opposing forces. The protagonist engages in the conflict with the antagonist, which may take the form of a character, society, nature (External Conflict), or an aspect of the protagonist’s personality (Internal Conflict) Connotation—associations and implications that go beyond the literal meaning of a word, which derive from how the word has been commonly used and the associations people make with it. For example, the word eagle connotes ideas of liberty and freedom that have little to do with the word’s literal meaning. Conventions—a characteristic of a literary genre (often unrealistic) that is understood and accepted by audiences because it has come, through usage and time, to be recognized as a familiar technique. For example, the division of a play into acts and scenes is a dramatic convention, as are soliloquies and asides, flashbacks and foreshadowing are examples of literary conventions. Denouement—a French term meaning "unraveling" or "unknotting," used to describe the resolution of the plot following the climax. Dialogue—the verbal exchanges between characters. Dialogue makes the characters seem real to the reader or audience by revealing firsthand their thoughts, responses, and emotional states. Diction— the connotation or associations of word choice. Just as with tone, all works have diction. Again, you must specify or qualify the diction. Instead of “The author’s diction was interesting, “ say, “Salinger’s slang-filled, often profane diction in The Catcher in the Rye captures the voice of its teenage narrator.” Drama—form of written composition designed for performance in the theater 2 Epiphany—in fiction or drama, when a character suddenly experiences a deep realization about him or herself; a truth which is grasped in an ordinary rather than a melodramatic moment Explication—a detailed analysis or “unfolding” of a small, rich piece of text Exposition—a narrative device, often used at the beginning of a work that provides necessary background information about the characters and their circumstances. Exposition explains what has gone on before, the relationships between characters, the development of a theme, and the introduction of a conflict. Fiction—in the broadest sense of the word, any writing that relates imagined characters and occurrences rather than recounting real ones. Defined more narrowly, fiction refers to prose narratives (specifically the short story and the novel.) Figurative Language—ways of using language that deviate from the literal, denotative meanings of words in order to suggest additional meanings or effects. Figures of speech say one thing in terms of something else, such as when an eager funeral director is described as a vulture. See also metaphor, simile. Flashback—a narrated scene that marks a break in the narrative in order to inform the reader or audience member about events that took place before the opening scene of a work. See also exposition. Foreshadowing—the introduction early in a story of verbal and dramatic hints that suggest what is to come later Frame Story—a story within a story; a narrative told within the framework of another fictional setting and situation Free indirect discourse—a narrative technique for providing the reader with a character’s speech, thoughts, or even unconsidered attitudes without the use of direct attribution by tag-phrase (he said/she said) or quotation marks. It typically uses the grammar of third person utterance to present us with a character’s thoughts. In the context of a novel, FID can be ambiguous: it could be the consciousness of the character referred to, or a statement from the narrator about the character. (Direct discourse: He said, “I love her.” Indirect discourse: He said he loved her. Free indirect discourse: He loved her.) Frequency—as a part of plot: Singulative: one event narrated once Multiple: a repeated event narrated the number of times is occurs Repetitive: one event narrated many times Iterative: many events narrated once 3 Genre—term that denotes the types or classes of literature (includes prose fiction, poetry, drama, non-fictional prose) Gothic—type of fiction that develops a brooding atmosphere of gloom and terror, represents events that are uncanny, macabre, or melodramatically violent, and often deals with aberrant psychological states. Image—a concrete representation of a sense impression, a feeling, or an idea. Imagery—when poets use language in ways that stimulate the reader’s senses or his/her imaginative recall of sense experience. The effect is to make a text more concrete rather than abstract. Internal monologue—differentiated from stream of consciousness in that it should only be applied when the words used to express the thoughts are those that the character is assumed to be using for thinking; it implies the use of language, whereas stream of consciousness doesn’t, necessarily; OR undertakes to present to the reader the course and rhythm of consciousness precisely as it occurs in a character’s mind. Irony—dissembling or hiding what is actually the case in order to achieve special rhetorical or artistic effects; OR recognition of a reality differing from the masking appearance. Dramatic irony—when the reader’s awareness of a reality differs from the reality the characters perceive Verbal irony—figurative language in which the intended meaning differs sharply form the literal meaning, eg. sarcasm, the taunting use of apparent praise for dispraise. Situational irony—when what occurs in the plot differs sharply from what the characters and/or readers expects. Juxtaposition—the direct comparison of opposite images or ideas; the effect is to highlight the distinctive characteristics of each. Leitmotif—(guiding motif) term applied to the frequent repetition within a single work of a significant verbal or musical phrase, or set description, or complex of images Magical Realism—a literary style in which writers interweave realism in representing ordinary events with fantastic or dreamlike elements. The fantastic elements are communicated in such a way as to make them seem as real and unquestionable as the ordinary elements. Metafiction—when at least part of a work of fiction is about writing a work of fiction; when an author comments directly on the nature or process of writing a work of fiction. Often done by means of narrative intrusion, when a narrator interrupts the telling of the story and introduces new or related information. 4 Metaphor—a comparison between essentially unlike things without a word such as “like” or “as” to designate the comparison. Modernism—literary movement that rejected Victorian standards and moved away from fixed narration and objectivity (e.g., multiple narrators, perspectives, unreliable narration). See also postmodernism. Motif—a conspicuous element, such as a type of incident, device, reference, or formula, which occurs frequently in works of literature. Mood—the emotional tone pervading a section or the whole of a literary work, which gives the reader certain expectations as to the course of events. Narration—the act of telling a story. May include objective (telling only what is seen and heard), omniscient (telling what is seen, heard, and thought), or limited omniscient (telling what is seen and heard, and some characters’ thoughts). Narrative structure—the structure of a story, including number and order of events, pace; overall pattern of a story Narrator—the character who “tells the story” in a text. Third person: someone outside the story proper who refers to all the characters in the story by name, or as “he”, “she”, “they”. First person: the narrator speaks as “I” and is to a greater or lesser degree a participant in the story. unreliable narrator—narrator whose perception, interpretation, and evaluation of the matters s/he narrates do not coincide with the opinions and norms implied by the author, which the author expects the alert reader to share. Novel—extended work of fiction written in prose. The novel narrates the actions of characters who are entirely the invention of the author and who are placed in an imaginary setting. The fact that a so-called historical or biographical novel uses historically real characters in real geographical locations doing historically verifiable things does not alter the fictional quality of the work. Note: plays, short stories, essays, and poetry are not novels, even if they appear in book-length works. Book≠novel. Novella—work of prose fiction, longer than a short story, shorter than a novel, typically between 60-130 pages. Pace—the speed at which a story is told, including length of time and number of events covered in the story. Parody—A humorous or mocking imitation of another, usually serious, work. It can take any fixed or open form, because parodists imitate the tone, language, and shape of the original in order to deflate the subject matter, making the original work seem absurd. 5 Anthony Hecht’s poem "Dover Bitch" is a famous parody of Matthew Arnold’s wellknown "Dover Beach." Parody may also be used as a form of literary criticism to expose the defects in a work. But sometimes parody becomes an affectionate acknowledgment that a well-known work has become both institutionalized in our culture and fair game for some fun. For example, Peter De Vries’s "To His Importunate Mistress" gently mocks Andrew Marvell’s "To His Coy Mistress." Pathetic fallacy—A fallacy of reason in suggesting that nonhuman phenomena act from human feelings, as suggested by the word "pathetic" from the Greek pathos; a literary device wherein something nonhuman found in nature—a beast, plant, stream, natural force, etc.—performs as though from human feeling or motivation. In Jack London's To Build a Fire, "The cold of space," London writes, "smote the unprotected tip of the planet, . . ." The word "smote" suggests nature deliberately striking the northern tip of the earth with severe cold. The poetry of William Wordsworth is replete with instances of pathetic fallacy—weeping streams, etc. Pathos—a scene or passage that is designed to evoke the feelings of tenderness, pity, or sympathetic sorrow from the audience. See also bathos. Personification-- A form of metaphor in which human characteristics are attributed to nonhuman things. Personification offers the writer a way to give the world life and motion by assigning familiar human behaviors and emotions to animals, inanimate objects, and abstract ideas. For example, in Keats’s "Ode on a Grecian Urn," the speaker refers to the urn as an "unravished bride of quietness." See also metaphor. Plot—the events and actions in a narrative work, as they are rendered and ordered toward achieving particular artistic and emotional effects Plot order (anachrony—any deviation from strict chronological progression; analepsis—“flashback”; prolepsis— “flashforward”) Subplot—a second story that is complete and interesting in its own right Duration—the relationship between narrating and narrated time Ellipses—a gap in the information provided for the reader, which may be permanent or temporary. Ellipses can be marked or unmarked—ie., the author may or may not make the reader aware of the gap. Frequency—as a part of plot: Singulative: one event narrated once Multiple: a repeated event narrated the number of times is occurs Repetitive: one event narrated many times Iterative: many events narrated once Point of view (also perspective)—Refers to who tells us a story and how it is told. What we know and how we feel about the events in a work are shaped by the author’s choice of point of view. The teller of the story, the narrator, inevitably affects our understanding of the characters’ actions by filtering what is told through his or her own perspective. The 6 various points of view that writers draw upon can be grouped into two broad categories: (1) the third-person narrator uses he, she, or they to tell the story and does not participate in the action; and (2) the first-person narrator uses I and is a major or minor participant in the action. In addition, a second-person narrator, you, is also possible, but is rarely used because of the awkwardness of thrusting the reader into the story, as in "You are minding your own business on a park bench when a drunk steps out and demands your lunch bag." An objective point of view employs a third-person narrator who does not see into the mind of any character. From this detached and impersonal perspective, the narrator reports action and dialogue without telling us directly what the characters think and feel. Since no analysis or interpretation is provided by the narrator, this point of view places a premium on dialogue, actions, and details to reveal character to the reader. See also narrator, stream-of-consciousness. Qualify (also “qualify your terms”)—specifying the type of literary technique the author uses. All authors use tone, diction, and syntax, for example, so you must specify or qualify the type of tone used. Don’t just say, “The paragraph has tone.” Better: “The author’s angry tone in the third paragraph shows that she has not forgiven her brother.” Instead of “The author’s diction was interesting,” say, “Salinger’s slang-filled, often profane diction in The Catcher in the Rye captures the voice of its teenage narrator.” Weak: “The author uses syntax to show his views of nature.” Better: “The author uses long, compound-complex sentences to show his overwhelming love of nature, specifically the forest where he goes nutting.” If there are many possible types of the literary technique the author uses, be sure to qualify your terms by specifying the type used. Postmodernism—(succeeded Modernism after WW2) While modernism presents a fragmented view of human subjectivity as tragic, something to be mourned and lamented, postmodernism tends to celebrate the incoherence as part of a meaningless world. See also modernism. Realism—the depiction of events, characters, and settings as they are in real life, without embellishment or exaggeration. Resolution—the events following the climax of a story. See also denouement. Rising Action—the events leading up to the climax of a story Romanticism—a literary movement in England (approximately 1780s-1830s) that favored innovation over traditionalism, emphasizing the ability of nature to stimulate thought, the lone figure on a quest, the use of common language, and spontaneity of composition. See also stream of consciousness. Be careful not to confuse Romanticism with romance or romantic, as in movies with Hugh Grant or Meg Ryan. Satire—the literary art of diminishing or derogating a subject by making it ridiculous and evoking toward it attitudes of amusement, contempt, scorn, or indignation. 7 Setting—the physical and social context in which the action of a story occurs. The major elements of setting are the time, the place, and the social environment that frames the characters. Setting can be used to evoke a mood or atmosphere that will prepare the reader for what is to come, as in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short story "Young Goodman Brown." Sometimes, writers choose a particular setting because of traditional associations with that setting that are closely related to the action of a story. For example, stories filled with adventure or romance often take place in exotic locales. Simile—a comparison between two distinctly different things as explicitly indicated by the word “like” or “as”. Stream of Consciousness—representation in words of a succession of thoughts in a character’s mind, typically when the character is alone and is allowing thought to follow thought without external prompting Structure—a reader’s sense of a text’s overall organization and patterning; the way its component parts fit together to produce a totality. Style—the distinctive and unique manner in which a writer arranges words to achieve particular effects. Style essentially combines the idea to be expressed with the individuality of the author. These arrangements include individual word choices as well as matters such as the length of sentences, their structure, tone, and use of irony. See also diction, irony, tone, syntax, imagery and other literary techniques. Surrealism—a cultural movement, partly in reaction to the first World War, featuring the element of surprise, juxtaposition, and non sequitur (a jump to apparently unrelated material). Suspense—a lack of certainty on the part of the reader about what is going to happen, especially to characters with whom the reader has established a bond of sympathy Symbol—a concrete object used to represent an abstract idea. Syntax-- Sentence structure, including sentence length and pattern. As with diction and tone, you need to qualify or specify the syntax. Don’t just say, “The author uses syntax to show his views of nature.” Better: “The author uses long, compound-complex sentences to show his overwhelming love of nature, specifically the forest where he goes nutting.” See handout on syntax for more details. Theme—a general concept or doctrine, whether implicit or asserted, which an imaginative work is designed to incorporate and make persuasive to the reader Tone— the writer or speaker’s attitude toward the subject, audience, or events of the text. Word choice (diction), details, imagery, and sentence structure (syntax) all contribute to the understanding of tone. Tone is the result of other literary choices made 8 by the author. Keep in mind that all texts have tone. Don’t just say, “The paragraph has tone.” Specify or qualify the tone. “The author’s angry tone in the third paragraph shows that she has not forgiven her brother.” See handout on tone for more details. Verisimilitude—the appearance of being real. The use of lifelike details to create the semblance or appearance of reality in a text. Poetry Terms Meter—the rhythmic pattern of a poem or lines of a poem Types of meter: Monometer—a one-foot line (“Thus I / Passe by, / And die: /…”) Dimeter—a two-foot line (“When up aloft / I fly and fly / I see in pools / The shining sky /…”) Trimeter—a three-foot line Tetrameter—a four-foot line Pentameter—a five-foot line Hexameter—a six-foot line Iamb/Iambic—light followed by heavy stress (machine) Trochhee/Trochaic—heavy followed by light stress (paper) Dactyl/Dactylic—heavy followed by two light stresses (wheelbarrow) Anapest/Anapestic—two light followed by one heavy stress (Tennessee) Spondee/Spondaic—(not properly a meter but used with some frequency) two syllable construction with no or equal inflection (blue moon) Caesura—a structural and logical pause within the line (usually within a metrical foot); not part of the metrical pattern Scansion—the mechanical notation of the metrical pattern of a poem; process of noting every syllable in every word Allows for recognition and scrutiny of the prevailing pattern and its variations Syllables given heavy stress are indicated by a macron ( ¯ ) placed over that syllable; syllables given light stress are indicated by a breve ( ˘ ) placed over that syllable Foot—a single emphasis plus details—one heavy stress plus whatever light stresses are needed to make up the chosen pattern Stanza—a group of lines in a poem that is separated by an extra amount of space from other groups of lines, or other stanzas Blank verse—unrhymed iambic pentameter Rhyme patterns: Couplet— Two consecutive lines of poetry that usually rhyme; aa bb cc dd, etc. Quatrain—a four line stanza, unified by a rhyme scheme; abab, cdcd, etc. Sestet—a six line stanza, unified by a rhyme scheme; cddcee, cdecde, etc. Octave—an eight line stanza, unified by a rhyme scheme; abbaabba, etc. Tercet—a three line stanza, unified by a rhyme scheme; aaa, bbb, aba, cdc, etc. Terza Rima—an interlocking three-line rhyme scheme; aba bcb cdc ded, etc. 9 Ode—a formal or ceremonial lyric poem of a serious nature, with an elevated style and elaborate verse form Ballad—a poem which tells a story, usually in short rhyming verses with frequent repetition of words or lines, intended to be sung or recited Sonnet—poem of 14 lines, usually iambic pentameter. Sonnets may follow a strict form (see below) or combine or borrow from different forms. Italian or Petrarchan sonnet: abba abba cde cde (or some variation); the first 8 lines set out statement or premise, the following 6 respond to it English or Shakespearean sonnet: abab cdcd efef gg; three quatrains and a final couplet Villanelle—A fixed form of poetry consisting of nineteen lines divided into six stanzas: five tercets and a concluding quatrain. The first and third lines of the initial tercet rhyme; these rhymes are repeated in each subsequent tercet (aba) and in the final two lines of the quatrain (abaa). End Rhyme—a rhyme that occurs in the last syllables of verses Internal rhyme—rhyme within a line and another word, either at the end of the same line or within another line Masculine rhyme—words rhyme on a single stressed syllable Feminine rhyme—words of more than one syllable that end with a light stress (buckle and knuckle) True rhyme (tears and spears) Slant rhyme (down and noon) Sound Alliteration—the repetition of consonant sounds at the beginning of words Assonance—the repetition of similar vowel sounds in a sentence or a line of poetry Consonance—the repetition of consonant sounds at the middle or end of words Tone Denotation—the dictionary definition of a word Connotation—the personal and emotional associations called up by a word Figures of Speech Apostrophe—An address, either to someone who is absent and therefore cannot hear the speaker or to something nonhuman that cannot comprehend. Apostrophe often provides a speaker the opportunity to think aloud. Hyperbole—a boldly exaggerated statement that adds emphasis without in-tending to be literally true—may be used for serious, comic, or ironic effect Litotes—a form of understatement that purposefully represents a thing as much less significant than it is, achieving the ironic effect of conveying its significance Synecdoche—a part of something substituted for the whole (workers = “hands”, cars = “wheels”) Metonymy—a closely related term is substituted for an object or idea (“the oval office” = the president, “the grave” = death) Synesthesia— one sensory experience described in terms of another sensory experience 1 0 (“seeing sounds” or “hearing colors”) Turning the line—defining/deciding where one line ends and the next begins Self-enclosed line—end-of-line pause is accentuated because the line is either an entire sentence or a phrase complete in terms of grammar and logic Enjambment—end-of-line/turning of line interrupts a logical phrase. The effect is to speed the line Epistrophe—ending a series of lines, phrases, sentences, or clauses with the same word Anaphora—repetition of a word or words beginning of lines in poetry Drama Terms Anagnorisis (or disclosure, discovery, recognition) This term comes from Aristotle’s Poetics (330 BC) in which he outlines what he sees as the basic elements of a tragedy. Anagnorisis is the “recognition” or“disclosure” by a character. Amphitheater An Amphitheater is a type of theater space used in ancient Greece. The orchestra was a circular area at the bottom where the action took place. The theatron was a semicircular sloping hillside that was terraced, and into which was placed benches capable of seating about 15,000 people. Actors wore large masks to facilitate the rapid change of roles and to communicate in the large space by capturing and emphasizing the essential qualities of each character. Aside Words spoken by an actor directly to the audience, which are not "heard" by the other characters on stage during a play. In Shakespeare's Othello, Iago voices his inner thoughts a number of times as "asides" for the play's audience. Bare Stage Term used to refer to Shakespeare’s stage which was signified by minimal set pieces and decoration. Blocking The placement and movement of the actors on stage moment by moment, usually planned by the director. Catharsis The emotional effect a tragedy has on its audience. Aristotle coined the term in the Poetics. Catharsis is the feeling an audience has while viewing a tragedy. Aristotle argued that tragedy “cleanses” the emotions for the audience. An audience vicariously experiences the tragic events along with the tragic hero. Chorus A group of people who sang or danced in Greek drama, commenting on the action of the play. By Elizabethan times the chorus was rarely used, in favor of a single character 1 1 delivering a prologue and an epilogue. Modern usage of the chorus is often a character in the context of the play who comments on characters and events, thereby giving additional perspective. Comic Relief A humorous scene or passage inserted into an otherwise serious work. Comic relief provides an emotional outlet and a change of pace for the audience. It also serves to contrast and further heighten the seriousness of the work. Closet Drama A play suited only for reading, not for acting. Most nineteenth-century English poetic dramas (e.g., Coleridge’s, Shelley’s Tennyson’s) fit into this category. Deus Ex Machina A Greek term meaning “the God from the machine.” (1) In Greek drama a god who descends by a crane-like arrangement and solves a problem in the story, thus allowing the play to end. (2) Any unexpected and improbable device (e.g., an unexpected financial windfall) used to solve a problem and thus conclude the work. Dramatic Naturalism This idea was first theorized by Emile Zola, a French novelist and playwright. The naturalists argued that plays should be a slice of life that demonstrates the effects of heredity and environment. Naturalism was the first artistic movement to treat working class characters with the same seriousness accorded the middle and upper classes. In the 20th century, naturalism is often used as a label for plays that seek to recreate the details of everyday life. Epilogue The concluding section of a work. It is also the recitation by an actor of the concluding section of a play that often requests appreciation and kind reviews. Fourth Wall A phrase that refers to the opening at the front of the stage. It is the imaginary wall through which an audience looks into a room. To “break” the fourth wall means to step outside of the stage space, either by directly addressing the audience or physically stepping into the audience viewing space. Globe Theater Shakespeare’s theater held three thousand persons. The configuration of the stage meant that no one was very far away from the action. There were no intermissions, and the Globe served beer, wine and sold playing cards. The atmosphere was one of a sporting event. The challenge for the performers was to keep the audience quiet through skillful performances. Groundlings 1 2 Term coined in Hamlet to refer to the spectators who attended performances at the Globe theater who paid less to stand in the yard. The were not under the roof, and therefore subject to the weather. They were often drunk and rowdy Hamartia This Greek word is variously translated as “error” or “shortcoming” or “weakness.” It is an error in judgment or an ignorance of certain facts that leads to the hero’s downfall or reversal in fortune. It is often caused by the tragic flaw. In Medias Res Literally translated, “in the middle of things.” Monologue An extended narrative, which can be oral or written, delivered uninterrupted by one person although it may be heard or witnessed by others. Peripety A reversal of fortune. Prologue An introductory statement preceding a literary work; in Greek tragedy the opening section of a play. Scenery The carpentry and painted cloths (and projected images) used on a stage. Scenery may be used to conceal parts of the stage, to decorate, to imitate or suggest locales, to establish time or to evoke mood. Soliloquy A type of monologue performed onstage as part of a play in which a character reveals their inner thoughts and feelings out loud while alone. Spoken Decor In Elizabethan theater, the idea that scenery was described in detail through words. Because there were no elaborate set pieces, Shakespeare’s plays relied on descriptive detail in speeches to set the scene. Tragedy A play written in an elevated, poetic style dealing with events that depict man as a victim of destiny yet superior to it, both in grandeur and in misery. In drama a work that presents the downfall of its noble protagonist through some error in judgment or personal weakness. According to Aristotle’s definition of tragedy in the Poetics, a tragedy contains elements of the supernatural, a tragic hero who has a tragic flaw which leads to his downfall, and catharsis for the audience. Unity 1 3 This term generally means something like “coherence”, “congruence”; in a unified piece the parts work together and jointly contribute to the whole. Unity suggests“completeness” or “pattern” resulting from a controlling intelligence. In the Poetics, Aristotle says that a tragedy should have a unified action, and he mentions that most tragedies cover a period of twenty-four hours. Works Cited Many definitions of these terms are found in these sources: Abrams, M.H. A Glossary of Literary Terms. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace College Publishers, 1999. Diyanni, Robert. Reading Poetry: an Anthology of Poems. New York: Random House, 1989. "Glossary of Literary Terms." The Meyer Literary Site. Bedford/St. Martin's. 20 June 2007 <http://www.bedfordstmartins.com/literature /bedlit/glossary_p.htm>. Hawthorn, Jeremy. Studying the Novel. London: Oxford University Press, 2001. Merriam Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature. Springfield, Massachusetts: MerriamWebter, Incorporated, 1995. Murfin, Ross, and Supryia M. Ray. The Bedford Glossary of Critical and Literary Terms. Second ed. New York: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2003. 1 4