Roberta Clemente - Assembleia Legislativa do Estado de São Paulo

advertisement

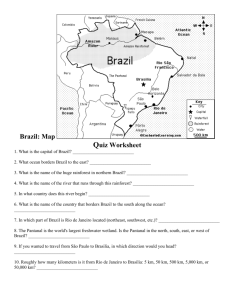

District Level parties within a federation: testing some institutionalist hypothesis in Brazil1 Roberta Clemente Political parties solve problems that are specific to democracies, particularly collective action and social choice problems. Parties also transform social power into political power and fulfill and the political ambition of politicians. A by-product of the political ambition of office-seekers is the accountability of the public polices implemented: they must be responsive to the voters, in order to win elections, given that the voters can reward or punish unresponsive politicians through elections. But the political accountability through elections is very difficult if the parties are not institutionalized in society, if they appear and disappear instantly, if parties’ labels have no meaning because there’s no party discipline and politicians can switch parties at will. Brazil has a history of weakly institutionalized party systems in comparative standards, with high electoral volatility, parties with poor roots on society and parties that quickly appear and disappear. Also, the Brazilian 1988 Constitution has the ability combine plebiscitary presidentialism, permissive electoral laws that favor personalistic appeals of candidates over parties, a weak and fragmented party system, a strong federalism that, according to 1 Final Paper presented for the course Comparative Party Systems - Professor Dr. Kenneth Greene – Stepan (1997) is the most “demos-constraining” in the world, malapportionment, and several points of vetoes. In sum, the Brazilian institutions have the effect of joining together the worst of two worlds: Executive predominance given by the plebiscitary presidentialism, which is usually coupled with bipartism in majoritarian systems, but in Brazil, it is coupled with federalism and proportional representation, which leads to multipartism, typical of consociative systems. The result could only be stalemate and democratic instability. Nevertheless, after 15 years of the constitution promulgation, Brazilian democracy persists; its first test was the impeachment of the first directly elected president after redemocratization for blatant corruption, by Congress, within the rules of the democratic game. Also, major structural economic and constitutional (the constitution is also criticized by its length and for being exhaustive detailed) reforms were undertaken, some of them very unpopular (like the social security reform, the break of state monopolies, the Fiscal Stabilization Fund and the Fiscal Responsibility Law) not by decree, but approved by Congress, within the democratic and prevailing constitutional rules. This is very impressive, considering that the State in Brazil, due to colonial legacies preceded the nation and throughout its history, the role of the state University of Texas at Austin, fall 2003 surpassed the role of civil society and all changes, until 1982 were top-down (independency, republic, Estado Novo, extension of suffrage, redemocratization in 1945, the military coup in 1964, and the deterioration of the military regime in the late 1970’s). Not surprisingly, the social cleavages in Brazilian’s society never had the chance to be crystallized and become political issues; therefore the social cleavages approach proposed by Lipset and Rokkan (1967) is inadequate for understanding Brazilian party system. But, given the incongruous set of institutions provided by the 1988 Constitution, Brazil is a very interesting case for studies of parties using an institutionalist approach. The first set of rules that should be looked at for this study is the electoral institutions. Brazil has an open-list proportional representation system, in which the legislative candidates must belong to a party in order to appear in the ballot, the district matches the state and its size varies from a minimum of 8 and a maximum of 70 (since 1994, before it varied from 4 to 60). The number of candidates each list can present equals to 1.5 the total number of seats and if there’s an electoral coalition with two or more parties, the maximum number of candidates for the coalition list is twice the number of seats. After the election, the total of valid votes is divided by the total number of seats, which generates the electoral quotient. Then, each list’s total of votes is computed and divided by the electoral quotient, which gives the number of seats each list secured. The occupants of these seats will be the candidates with larger total of votes in every list, that’s why is called open-list, the ranking of the list is decided by the voter, not by the party. The defendants of this system argue that this system grants that every voter will be represented, contrary to the majoritarian system, in which only the electors of the winner are represented. The critics to this system claim that this systems causes serious distortions and the voter loses control of his or her vote, that might benefit another candidate of the same party that he or she wouldn’t want to elect, and also that a candidate that received 70 thousands votes not be elected whilst a candidate from another list that received only 15 thousands votes gets the seat. Also, it creates a perverse situation for party leaders that have to chase candidates that attracts several votes even though he or she has no ideological attachments to the party. Besides, this system entices competition within candidates of the same party, which leads to the personalization of electoral campaigns and weakens the party cohesion. The large district magnitude coupled with the proportional representation system promotes multipartism. Also, multipartism is reinforced by law: no party can be registered at the Superior Electoral Court (Tribunal Superior Eleitoral) if in its statutes it does not respect the multipartism2. The steps to create a new party are: collect signatures of 101 Brazilian citizens supporting the future party’s statutes, with electoral residence in one-third of the states of the federation (nine states), register the future party’s program, statute and provisory director board. After that, the future party has one year to publish its statutes in the federal official paper (Diário Oficial da União), legally register its foundation in the Federal Capital and collect support of as many voters as 0.5% of the valid votes for the Lower Chamber in the previous elections. The voters must have electoral residency in at least nine states and at list 0.1% of the total electorate in each state. After that, the future party must register all its local, municipal, state and national organs with the Electoral Superior Court and if it has fulfilled all the requirements, it becomes a party and is entitled to the parties fund (Fundo Partidário), time on television broadcast and within a year, in the elections. Party organization, requisites for party affiliation and party discipline enforcements must be stated in the party’s statutes. 2 LEI Nº 9.096, 1995 (which disposes about political parties in Brazil) article 2 o. Until 2003, in Congress, all parties were entitled to a leadership office and aides (even if it had only one member) the committees assignments were proportionally distributed among the parties existing in the legislature and every leader had the right to join the Leaders College (Colégio de Líderes, organ who decides about the agenda of the legislature). Since February 2003, to be entitled to all this, a party must have acquired at least 5% of the votes for the Lower Chamber and at least 2% of the votes in nine states. The incentives were for the creation of parties, at least until 2003 to gain access to intralegislature benefits. And the high district magnitude coupled with the proportional representation system, gave little incentive for elite coordination and parties could sprout for whatever reason, given that could coordinate in at least nine different states. Mainwaring (1999) argues that a federal polity promotes party decentralization and party heterogeneity and in Brazil parties are federations of state parties. Brazil is a federation of 26 states plus the federal district, more than 5,500 municipalities and the central government. The leitmotif of the Brazilian federalism is the accommodation for the demands of conflicting elites and coping with great regional inequalities (C. Souza, 1998). Brazil has huge socio-economic disparities that are adjusted by malapportionment: the least populated and poorer states hold proportionally more seats in the Chamber of Deputies than bigger constituencies. This was introduced in the 1930’s (along with proportional representation) to diminish the power of the states of São Paulo and Minas Gerais in the federation and the defenders of the malapportionment argue that the over representation of poorer units of the federation forces the federal government to incorporate the problems of Brazil's regional inequalities into the political agenda. The Brazilian federation has suffered several modifications since its first implementation in 1889, with the First Republic (Primeira República 18891930). During this period, the federal government was weak comparing to the states and was controlled by two oligarchies (from the States of São Paulo and Minas Gerais). Every state had only one party, with the exception of Rio Grande do Sul that had two parties. The votes had little significance, electoral fraud was the rule and the legislatures had the power to verify the legality of its elected members before installation. The ruling oligarchies during the Republic were already powerful during the Empire (1822-1889). In 1930, there was a revolution and Getulio Vargas came to power. Parties were suppressed3 and the State apparatus was expanded. For the States, Vargas nominated delegates (interventores) and the federalism was also suppressed. In 1946, the new constitution reestablished the federalism with a new member besides the states and the union, the municipalities. Some of the Central power was decentralized to the States and municipalities, but the Union was stronger comparing to the First Republic and the States much weaker (some of their powers present in the First Republic were transferred to the Union and some to the municipalities). The centralization of power occurred once more during the military regime (1964-1985) and the struggle for democratization was confounded with demands for fiscal and administrative decentralization. The 1988 Constitution granted the municipalities an unprecedented autonomy fiscal and administrative, established mandatory transfers from the federal government to the municipalities and states without corresponding responsibilities. In comparison with other federations, the revenue share among levels of government in Brazil is: 3 with the exception of the period 1934-1937, when suffrage was extended, and several parties were created, and there were two kinds of representatives: the ones linked to parties and the “class representatives” (deputados classistas, elected indirectly according to the union they represented). Table 1 Total expenditure by level of government in some federal countries Country Canada USA Austria Australia Brazil Brazil Year 1992 1992 1992 1992 1987 1992 Federal 41.3 60.3 70.4 52.9 65.8 56.0 State 40.3 17.3 13.7 40.4 24.5 28.0 Local 18.4 22.4 16.9 6.8 9.6 16.0 Source: Spink et al (1998 p. 3) The graph bellow shows the variation of expenditure within governments level in Brazil across time: 80 70 60 50 FEDERAL 40 STATE 30 LOCAL 20 10 1998 1995 1992 1989 1986 1983 1980 1977 1974 1971 1960 0 Source: Rezende and Afonso (2001) Since 1982, the federal government resources have been decentralized to states and municipalities. And in 1982, were held the first direct elections for governor since the military coup, in 1964, along with elections for state and federal legislatives. The impact of electoral institutions in the party system of a federal polity has deserved a close attention by scholars (Chhibber and Kollman 1998, Desposato 2003, Thorlakson, 2003). Chhibber and Kollman argue that the more resources are decentralized in a federation; more important will be state level in shaping the party system. Also, Thorlakson (2003) compared party systems in six federations (Austria, Australia, Canada, Germany, Switzerland and the United States) and concluded that resource and policy decentralization lead to less vertical integration and more decentralized parties. Samuels (2000) concluded that gubernatorial race, instead of presidential race, shape the congressional elections in Brazil, because governor’s can control the resources needed by the congressional candidates to get in the ballot and be elected or re-elected. The state-level has been recognized as important for shaping the federal legislature, but the elections within states and across states in Brazil haven’t deserved much attention. The electoral rules are the same but the district magnitude and the resources controlled by each state vary drastically among the Brazilian states. So there should be a comparative analysis of party system in each. The previous studies give us the following hypothesis: 1- The greater the district magnitude, the more parties will be: Brazil district magnitude varies from 6 (prior to the 1994 elections in smaller states) to 70 (São Paulo state after 1994). There should be more parties competing in the higher magnitude districts than in the lower (Durverger’s law). The maximum number of parties should range from 7 to 71, according to the district magnitude. To test this hypothesis we should consider the district magnitude and the number of parties competing in each district. There are the number of existing parties presenting candidates in the elections and the number of effective parties 1/(vj2)-1, an expression given by Laakso and Taagepera (1979 apud Cox 1997) that tries to account for only the real candidates, where vj is the vote share of the jth party. It is better to use the number of effective parties instead of parliamentary parties because to avoid distortions caused by how votes are translated into seats, particularly in Brazil, where in each state there might be coalitions for the legislative elections and, as being an open list system, a party’s vote share can be converted in another party’s seat. To check the association between district magnitude and the number of parties as well as the number of effective parties, data from all states (districts) were collected for the elections 1982, 1986, 1990, 1994, 1998 and 2002. In 1986 elections, the three territories (Amapá, Rondônia and Roraima) and the Federal District presented candidates for the first time. In 1988 a new state joined the federation (Tocantins, which was part of Goiás). The measures of association are: Measures of Association R R Squared Eta Eta Squared number of parties * District Magnitude ,191 ,036 ,463 ,214 effective parties * District Magnitude ,405 ,164 ,567 ,321 The Eta squared shows that there’s association between the magnitude of the district and the number of parties, that district magnitude can explain, in the case of the number of parties presenting lists, 21.4% of the variation. For the number of effective parties, the district magnitude can account for 32.1% of variation. But more than 70% cannot be explained by this model. So, there must be variation across states concerning the number of parties. Thorlakson (2003) proposes that if there’s locally defined and developed issue space and competitive dynamics, there must be a great variation in the parties that parties that compete, the number of parties in the system and in patterns of aggregate voter behavior. She argues that: “…the relative power of each level of government in a federation is a key institutional variable capable of influencing party strategy and political behaviour because it structures the incentives and opportunities that parties and voters face, and mediates the effect of social cleavages and broader processes of social transformation.4” This leads us to another hypothesis: 2- New parties should appear in the state-level after 1988’s Constitution, because the states have more resources automatically transferred from the federal government, which gives them more political independence. Otherwise, state elites should have incentives to align with national parties (Chhibber and Kollman 1998). Also, the number of parties in each district shall vary among states. To test this hypothesis we can check the number of parties in each district before (1982 and 1986 elections) and after decentralization (1990, 1994, 1998 and 2002): Measures of Association R R Squared Eta Eta Squared number of parties * Year ,869 ,755 ,898 ,807 effective parties * Year ,636 ,405 ,668 ,447 The measures of association confirm a strong relationship between the year of the election and the parties presenting lists of candidates: the Eta squared for the number of parties shows that the year of the election can account for 80% 4 Thorlakson (2003) pp. 03-4 of the variation in the number of parties. But for the effective number of parties, this model can only account for 44.7% of the variation. The Table bellow shows the means and standard deviation in the number of parties as well as in the number of effective parties according to the year5: Year 1 Mean N 23 23 ,487 11,58 2,38 26 26 Std. Deviation 5,247 ,698 Mean 17,96 4,07 27 27 Std. Deviation 4,146 1,519 Mean 17,85 4,61 Mean N 3 N 4 N 5 27 27 Std. Deviation 1,955 1,784 Mean 23,04 4,66 N 6 27 27 Std. Deviation 4,407 1,393 Mean 26,15 5,36 N Total effective parties 2,04 ,757 Std. Deviation 2 number of parties 3,87 27 27 Std. Deviation 2,507 1,652 Mean 17,10 3,91 157 157 7,979 1,805 N Std. Deviation The following graph confirms the evolution both in the mean of number of parties and in the mean number of effective parties per election year. 5 1=1982, 2=1986, 3=1990, 4=1994, 5=1998 and 6=2002. 30 25 parties 20 number of parties 15 effective parties 10 5 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Year One question that arises is: which states had the appearance of more parties: the wealthier or the more dependent of federal transfers, that after 1988 are more independent financially, since the transfers became mandatory instead of politically negotiated? To answer this question, we must first check if there’s any relationship between transfer dependency and the state’s wealth. There’s no data available prior to 1985 concerning wealth or transfer dependency of the States, therefore, only one election year prior to the 1988 Constitution is present in this study: 1988. Until 1994, Brazil’s economy was under hyperinflation and the change of currency was the rule. The data collected prior to 1994 (in several different currencies of different magnitudes) was already converted to Real in values of 1995. Despite the fact that there’s still 10 to 15% inflation a year in Brazil, the values collected for 1998 and 2002 were not converted to values of 19956. As shown in the following graph, the relationship between wealth and transfer dependency is not inversely proportional: Year 1,00 2 3 4 5 Mean Transfer Dependency 0,80 6 0,60 0,40 0,20 0,00 19949247046 6625990179 3810397085 2136477961 916546631,1 29488105,78 13633727,29 8437119,76 5669073,48 4825123,91 4099676,05 2986350,18 2429036,95 1810930,76 1600655,94 1296964,87 1022288,44 821840,38 693542,58 595601,63 503678,20 405882,33 160462,08 Wealth*Receita Corrente Liquida Measures of Association R Transfer Dependency * Wealth (Receita Corrente Liquida) 6 -,393 R Squared ,154 Eta ,636 Eta Squared ,404 By law all official records must be stated in Real and the use of monetary indexes is forbidden in an attempt to fade away the “inflationary memory” and automatic indexation of the economy. It is possible to convert the currency to values of 1995, but an official distortion of the data was preferred to an informal distortion, which is also beyond the purpose of this work. But the reader must be aware that there is a distortion. The Eta squared of the association, is 0.251, which means that only a quarter of the transfer dependency can be accounted for the wealth of the state. The wealth of the state is measured by the Receita Corrente Líquida, which means all the net resources of the states, excluding mandatory transfers for the municipalities. There was no available data to further investigate the percent of mandatory and voluntary transfers received by each state in those election years, so the relationship between the sort of transfer received and its effects on the parties in the states could not be measured, in order to test the if states that received more “negotiated” transfers from the federal government have less parties than states that received more mandatory transfers. ANOVA Table Sum of Squares effective parties * Wealth*Receita Corrente Liquida number of parties * Wealth*Receita Corrente Liquida Between Groups Mean Square df F Sig. (Combined) 169,363 20 8,468 3,984 ,000 Linearity 100,421 1 100,421 47,247 ,000 68,942 19 3,629 1,707 ,045 Within Groups 240,174 113 2,125 Total 409,536 133 (Combined) 2656,203 20 132,810 5,897 ,000 Linearity 2268,738 1 2268,738 100,728 ,000 387,465 19 20,393 ,905 ,577 Within Groups 2545,140 113 22,523 Total 5201,343 133 Deviation from Linearity Between Groups Deviation from Linearity Measures of Association R R Squared Eta Eta Squared effective parties * Wealth*Receita Corrente Liquida ,495 ,245 ,643 ,414 number of parties * Wealth*Receita Corrente Liquida ,660 ,436 ,715 ,511 The relationship between number of effective parties and wealth has the Eta squared equal to 0.414. This means that 41.4% of the number of effective parties can be accounted for by the wealth of the state. As for the number of parties, the association is even stronger: the Eta squared is 0.511. The association between transfer dependency and the number of effective parties is not so strong: the Eta squared is only 0.231. As for the number of parties, the Eta squared is 0.208. So a better predictor for the number of parties is the state wealth, not its transfer dependency, which is calculated as the percent of federal transfers (mandatory or not) in the states’ Receita Corrente Líquida. 19949247046 9988203682 5364990867 3810397085 2562885510 1834112456 916546631,1 38215351,22 19529684,84 13633727,29 8876276,82 7517569,37 5669073,48 4928985,30 4693279,83 4099676,05 3205961,07 2848134,77 2429036,95 2077793,39 1745892,26 1600655,94 1384538,57 1163288,20 1022288,44 979874,60 782373,81 693542,58 602280,41 574941,09 503678,20 425443,13 312027,00 160462,08 6 4 Mean effective parties 20 15 Mean number of parties 30 25 10 5 Wealth*Receita Corrente Liquida 10 8 2 0 19949247046 9988203682 5364990867 3810397085 2562885510 1834112456 916546631,1 38215351,22 19529684,84 13633727,29 8876276,82 7517569,37 5669073,48 4928985,30 4693279,83 4099676,05 3205961,07 2848134,77 2429036,95 2077793,39 1745892,26 1600655,94 1384538,57 1163288,20 1022288,44 979874,60 782373,81 693542,58 602280,41 574941,09 503678,20 425443,13 312027,00 160462,08 Wealth*Receita Corrente Liquida As for Transfer dependency, the following graphs show the distribution: 10 Mean effective parties 8 6 4 2 0 ,98 ,87 ,80 ,75 ,70 ,66 ,64 ,59 ,58 ,55 ,53 ,52 ,51 ,49 ,46 ,40 ,39 ,36 ,32 ,31 ,28 ,27 ,23 ,21 ,20 ,19 ,17 ,16 ,15 ,13 ,12 ,10 ,08 ,03 Transfer Dependency 30 Mean number of parties 25 20 15 10 5 ,98 ,87 ,80 ,75 ,70 ,66 ,64 ,59 ,58 ,55 ,53 ,52 ,51 ,49 ,46 ,40 ,39 ,36 ,32 ,31 ,28 ,27 ,23 ,21 ,20 ,19 ,17 ,16 ,15 ,13 ,12 ,10 ,08 ,03 Transfer Dependency A conclusion that can be drawn is that the wealth of the states affects more the variation in the number of parties and effective parties than their transfer dependency, if the proportion of mandatory and voluntary transfers from the federal government can not be disaggregated. So far, how much of the variation of the number of parties and effective parties in districts of a federation can the institutionalist theories account for? For the number of parties, the variables year, district magnitude and wealth can account for 69.3% of its variation. For the number of effective parties, these variables can explain 50.2%. This difference might be caused by the psychological effect: hopeless candidates and lists are deserted by voters who do not want to waste their votes. The addition of the transfer dependency variable does not affect the fitness of the model nor has the variable state. But the addition of the variable after 1989 (a dummy variable with values 0 for before 1989 and 1 for after), makes the model account for 55.1% on the variation of the number of effective parties. The same occurs with the number of parties’ variable: the addition of the dummy “after 1989” improves the model to account for 70.2%. The variables state and transfer dependency have little effect on the model. Thorlakson (2003) studied party systems in six cases: Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Australia, the United States and Canada – all western industrialized countries that have been continuously democratic during 1945- 2000, period of her study comparison. Chhibber and Kollman (1998) compared the United States and India, a western economically developed country and an eastern emerging country, with great ethnic, linguistic and religious diversity; but both with single-member simple plurality electoral system. This paper tested their hypothesis in a new democracy (as opposed to consolidated), in a developing country with proportional representation and a low degree of institutionalization of its party system (Mainwaring 1999) and the decentralization hypothesis fits. Deeper analyses are required for Brazil: the programmatic diversity and vote shares of parties among the different districts, as well as the uniformity of the coalitions across states and in different years. If ever the data is available, there should be a comparison on the share of voluntary transfers received from the federal government and the parties existing in the states. Also, there must be some further investigation on what variable can be added to improve the model in predicting the number of effective parties. Also, this hypothesis should be tested in other federalist countries, with different party systems and electoral institutions and different levels of economic development, stages of democracy consolidation and decentralization. Roberta Clemente is a Master in Public Administration and Government at the Getulio Vargas Foundation in São Paulo, Brazil, where she currently is a PhD candidate. Also, works at São Paulo State Legislature. References ABRÚCIO, Fernando Luiz. Os Barões da Federação: os governadores e a redemocratização brasileira. São Paulo: Hucitec/Departamento de Ciência Política, USP, 1998 CHHIBBER, Pradeep and Ken Kollman. Party Aggregation and the number of parties in India and the United States. American Political Science Review. June 1998 v92 n2 p329 (14) CLEMENTE, Roberta. Evolução Histórica das Regras doJogo Parlamentar em uma Casa Legislativa: O caso da Assembléia Legislativa do Estado de São Paulo. Dissertação apresentada ao Curso de PósGraduação da FGV/EAESP Área de Concentração: Administração Pública e Governo como requisito para obtenção de título de mestre em Administração. São Paulo:2000. (unpublished) COX, Gary. Making Votes Count: Strategic Coordination in the World’s Electoral Systems. New York: Cambridge University Press. 1997 DESPOSATO, Scott W. The Impact of Federalism on National Party Cohesion in Brazil. Working paper. 2003 FAUSTO, Bóris. História do Brasil. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo: Fundação para o Desenvolvimento da Educação, 1999 (Didática 1) FIGUEIREDO, Argelina Cheibub e LIMONGI, Fernando. Partidos Políticos na Câmara dos Deputados: 1989 - 1994. Dados - Revista de Ciências Sociais, Rio de Janeiro, Vol. 38, n. 3, 1995, pp. 497 a 525 IPEA - Instituto de Pesquisas Econômicas Aplicadas. Contas Estaduais Brazil 1985-2001 http://www.ipeadata.gov.br/ipeaweb.dll/ContaEstadual.htm LIMA JÚNIOR, Olavo Brasil de. Instituições Políticas Democráticas: o Segredo da Legitimidade. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar Ed., 1997 LISPET, Seymour Martin and ROKKAN, Stein. Cleavage Structures, Party Systems, and Voter Alignments: An Introduction. in Peter Mair (ed.) The West European Party System. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990 MAINWARING, Scott. Rethinking Party Systems in the Third Wave of Democratization: The Case of Brazil. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999 MENEGUELLO Rachel. Partidos e Governos no Brasil Contemporâneo (1985-1997). São Paulo: Paz e Terra 1998 NICOLAU, Jairo Marconi. Dados eleitorais do Brasil 1982-2002. available at http://www.iuperj.br/deb REZENDE, Fernando and AFONSO José Roberto R. Fiscal Federalism: the Brazilian Case. Federalism Workshop, Stanford University, April/2001 Center for Research on Economic Development and Policy Reform SAMUELS, David Julian. Gubernatorial Coattails Effect: Federalism and Congressional Elections in Brazil. The Journal of Politics 62, 1 (February 2000), pp. 253 SANTOS, Wanderley Guilherme dos. Almanaque de Dados Eleitorais: Brasil e Outros Países. http://www.iuperj.br/leex/indice.htm Secretaria do Tesouro do Ministério da Fazenda. Estatística dos Estados 19851994 http://www.tesouro.fazenda.gov.br/estatistica/est_estados.asp Secretaria do Tesouro do Ministério da Fazenda. Estatística dos Estados 19952002 http://www.tesouro.fazenda.gov.br/estados_municipios/download/bala ncos_estados_1995_2002.zip SILVA, Pedro Luiz Barros. A Federação em Perspectiva: Ensaios Selecionados. – São Paulo: FUNDAP, 1995 SOUZA, Celina. Intermediação de Interesses Regionais no Brasil: O Impacto do Federalismo e da Descentralização, Dados 41(3),569-592, 1998 SOUZA, Maria do Carmo Campelo de. Estado e Partidos Políticos no Brasil (1930 a 1964). São Paulo: Alfa-Omega, 1976. SPINK, Peter, CLEMENTE, Roberta and KEPPKE, Rosane. Governo Local: o mito da descentralização e as novas práticas de governança. RAUSP - Revista de Administração. Volume 34 – número 1 – janeiro/março 1999.pp. 61-70 STEPAN, Alfred. Toward a New Comparative Analysis of Democracy and Federalism: Demos Constraining and Demos Enabling Federations. Paper presented at the Meeting of the International Political Science Association. 1997. THORLAKSON, Lori. An Institutional Explanation of Party System Congruence: Comparative Evidence from Six Federations. Paper prepared for the 3rd Annual State Politics and Policy Conference14 – 15 March, 2003Tucson, Arizona