- Football Coach U

advertisement

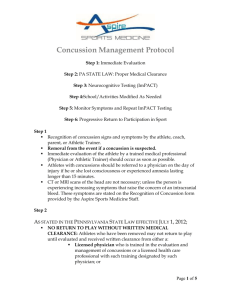

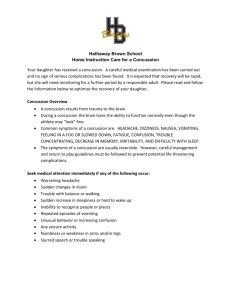

Special Report: Concussions & Neck Injuries in Sports – A Pro-Active Approach Jim Kielbaso MS, CSCS Adam Stoyanoff MS, CSCS Before we begin, it needs to be clear that there is inherent risk associated with playing sports, and there is no way to completely eliminate concussions and neck/spinal injuries. We do know, however, that there are ways that we can reduce the forces encountered by the head and neck, especially in sub-concussive blows. We can protect ourselves. The aim of this report is to arm you with information about concussions and neck/spinal injuries and what can be done to reduce an athlete’s risk. Rather than accepting the view that absolutely nothing can be done, we are taking a pro-active approach to the problem. We believe that proper use of safety equipment, coaching techniques, and comprehensive training of the head & neck musculature may be beneficial. There are really four basic components of neck injury and concussion prevention: 1. Protective equipment – In most sports, this means properly fit, quality helmets and mouth pieces. Unfortunately, no equipment or training currently known to us will eliminate concussions. “The best helmet on the market can still lead to injuries of the head including concussions,” said Scott Peck, a certified athletic trainer in Washington. “To decrease concussions, athletes need to practice good technique in tackling and blocking by keeping their heads away from contact.” As you will read later in this report, however, we now have ways of determining which helmets are better able to protect us. 2. Technique – Some sports include more contact than others. Good coaches always teach athletes not to initiate contact with the head, but we still see a lot of young athletes using poor form when tackling or hitting. 3. Awareness – It seems crazy, but there are still a lot of coaches, parents and coaches who simply do not understand how dangerous a concussion can be or that there is inherent risk involved in participating in most sports. This site was set up to help heighten awareness at the same time we discuss prevention options and proper treatment. 4. Training – This component is just now picking up momentum, but some coaches have known about this concept for years. This is also the least publicized aspect of concussion prevention for several reasons that are discussed further in this report. Research being done on strength development, combined with mathematical models derived from the auto industry are showing that a larger/more rigid neck can help dissipate forces during an impact. Comprehensive strengthening exercises for the head & neck seem to have the most promise, but vision/awareness training is another component that is being explored. Concussions and neck injuries have had a huge impact on sports. Recently, some of the greatest athletes in the world have been sidelined (potentially forever) by injuries. Peyton Manning and Kyle Vanden Bosch had to undergo surgery to repair damage in their necks. Vanden Bosch, who takes neck training very seriously, has made a full recovery. Sidney Crosby and Brian Westbrook were sidelined for an entire year due to concussions that may even be responsible for ending their careers. The sub-concussive blows that build up over the years may be even more devastating long-term. Even recently successful players like Wayne Chrebet are now suffering from the debilitating effects of concussions and piled-up sub-concussive blows. 6th grader Evan Coubal from Wisconsin and high schooler Ridge Barden are just two boys who have died due to head trauma suffered during sports. Their families will never see these boys again, and these are just two of many kids who have sustained life-threatening injuries. Our approach is similar to the ACL Prevention movement that has gained enormous popularity over the past 10 years. Ten years ago, ACL prevention programs were virtually non-existent. Today, female athletes all over the country understand that proper training will limit their risk of sustaining an injury. Yet, ACL injury rates haven’t slowed down. It doesn’t mean that the training has not helped. And, going through a training program does not mean you will never hurt yourself. Training is meant to reduce risk or severity of an injury. The same goes for properly training the neck & head to reduce the risk of concussions and serious neck injuries. The training does not eliminate the injuries, but it may help to lessen the risk or severity. The leading researcher on neck training, Ph.D. candidate Ralph Cornwell, put it best when he said “If we know that it might help, and it’s not going to hurt, why wouldn’t you want to do this kind of training? People do ACL prevention programs all the time. This is like an ACL prevention program for your brain and spinal cord. You can replace your ACL, but as far as I know, you only have one brain. It just makes sense to protect it.” Research done by the NFL is now revealing that the repetitive sub-concussive blows – the hits that don’t knock you out, but just ring your bell a little – may be the main culprit behind the long-term brain damage seen in many former athletes. Many of these athletes are now suing major sports organizations because they are mentally and physically disabled due to these blows. It seems that every brain has a certain number of hits it can take before long-term damage sets in. The more G-forces the brain encounters, the worse it gets. Training may reduce the G-forces encountered on these sub-concussive blows, raising the bar on the number of hits it will take before the long-term damage sets in. This is some of the best news ever presented on this topic, because it gives us hope that we may be able to combat this problem. Major sports organizations like USA Hockey and the NFL are recognizing that something must be done, so rules are changing quickly. Even Dr. Robert Cantu, who is considered one of the leading experts on the subject, has said that he thinks young athletes should wait until they are stronger and more mature before engaging in intense contact/hitting sports. This means that the leading authority on concussions understands that being stronger will have a positive effect and is part of the concussion prevention equation. With the knowledge that resistance training may help prevent injuries and, when done properly, can cause no harm, why would we NOT strengthen the muscles surrounding the head and neck? We also want to make it clear that most of this pro-active approach is based on theory. We acknowledge this and still feel it is incredibly valuable information that has the potential to help a lot of people. Many people completely accept that mouth-guard usage, which is now mandated by most football organizations, is an important part of concussion and injury prevention. Interestingly, all of the evidence supporting mouth-guard usage is based on the theoretical modals of Newtonian’s Law of Physics that states that an increased separation between two adjacent structures increases time to contact. All of this stuff is based on theory because it’s almost impossible to test in real life. Researching the benefits of training the musculature of the head and neck would be even more difficult to test in real life because of several complicated issues. First, most people don’t know how to safely and effectively train the head and neck musculature. In fact, most of the neck training being done in America is absolutely terrible and potentially dangerous. The use of neck harnesses, poorly spotted manual resistance and neck bridges are just some of dangerous methods we’ve seen. Isometric holds, exercises with balls and self-spotting are other techniques that are ineffective at best. The lack of neck training in college football, hockey, lacrosse and soccer is mind-blowing, and it’s MUCH worse at the high school level. Many coaches who don’t know how to safely and effectively train the neck simply don’t do it, which is leaving kids and parents in the dark. It’s certainly not easy to implement, but properly training the neck should be a priority for all coaches in contact sports. Second, it would be next to impossible to produce scientific evidence to show that training will help prevent concussions because you would have to use real human beings and expose them to potentially life-threatening blows. This would never pass any ethics committee, so the research probably cannot be done. Still, the automotive industry has known for years that a stronger and stiffer neck significantly reduces the G-forces encountered by crash test dummies in crash research. It seems obvious that a stronger neck would be extremely helpful during a blow to the head, but most doctors aren’t yet ready to admit that. That could be because: a. Doctors won’t make any money from the prevention side of this issue. b. Most doctors are probably unaware of how to properly train. c. The long-term effects of thousands of sub-concussive blows is nearly impossible to track. Reducing the forces encountered during these sub-concussive blows that build up over time may be the most important reason for strengthening the neck. d. Doctors typically refer to the scientific literature, but we already established that this evidence will probably never be published in any scientific journal. Sports Concussion Basics It is estimated that over 300,000 sports related concussions occur every year. Football has the highest rate of concussions, but ice hockey, soccer, lacrosse and field-hockey are not far behind, and younger athletes are more susceptible. Long-term research suggests that 10-15% (some as high as 20%) of participants in contact sports suffer a concussion. It has become such an epidemic that even Sports Illustrated has devoted considerable coverage to the issue. In lay terms, a concussion is a “brain sprain” or a “bruised brain.” A concussion is brain injury caused by a blow to the head, a fall, or another injury that jars or shakes the brain inside the skull. The brain is a soft organ surrounded by spinal fluid and protected by the hard skull which acts kind of like a helmet. Normally, the fluid around your brain acts like a cushion that keeps your brain from banging into your skull. But if your head or your body is hit hard, the brain can crash into your skull and get injured. The shaking causes energy to be created that travels through the brain, disrupting normal function. Some people will have obvious symptoms of a concussion, such as passing out or forgetting what happened right before the injury. But other people won’t. You don’t have to pass out (lose consciousness) to have a concussion. With rest, most people fully recover from a concussion, sometimes within a few hours, but it can sometimes take a few weeks (or even months) to recover from more severe blows. The human brain has not fully matured until the early 20′s. Younger brains take longer to recover from a concussion and may be more vulnerable to the effects of another concussion when it has not fully recovered from the previous one. In rare cases concussions cause more serious problems. Repeated concussions or a severe concussion may require surgery or lead to long-lasting problems. Because there is a chance of permanent brain problems, it is important to contact a doctor if you or someone you know has symptoms of a concussion. When in doubt – check it out. What Happens During a Concussion The human brain is very complex and it maintains a delicate balance between the chemicals inside and outside of its cells. During a concussion the membranes of the brain cells are distorted causing chemicals that are normally on the outside to rush inside the cells, forcing out the chemicals that are normally inside the cell. This starts what is known as a cascade of chemical changes in the brain. As it attempts to return to normal, the brain’s demand for energy (glucose or sugar) increases by about 150%. To complicate the issue, the brain’s ability to deliver the required glucose drops to only 50% of normal. This mismatch between supply and demand is what causes the problems after a concussion. Types of Sports Concussions Most sports concussions are divided into two types: simple and complex (also referred to as Uncomplicated or Prolonged). A simple concussion is when there is no detectable damage to the brain itself. A complex concussion is when there is overt or detectable damage to the brain such as a bruise or bleeding. Many doctors also use a grading system where concussions are rated as grade 1, 2, or 3. In reality, there are over 20 different grading systems that have been used. Unfortunately, none of the grading systems have effectively established treatment guidelines and none have been able to accurately determine recovery rates. When symptoms last more than three weeks, a diagnosis of Post Concussion Syndrome (PCS) is often made. It has been shown in research that dizziness directly after the injury often leads to an increased incidence of PCS. There are many medical options for athletes with PCS including therapy and medication. Concussion Symptoms You don’t necessarily have to lose consciousness to have a concussion, but if you did, then it is definitely considered a concussion. Just after a concussion an athlete may be confused and/or disoriented any may have a hard time recalling events immediately before or after the blow. The athlete’s balance may be affected and they may repeat themselves. Sensitivity to light and sound is common as well as headache and irritability. Below are common symptoms of a concussion: Headache Poor balance Nausea/Vomiting Affected smell Fatigue Irritability Affected hearing Tearfulness/Sadness Feeling slowed down Increased sleep Decreased appetite Feeling “foggy” Decreased sleep Sensitivity to light or noise Blurred vision Poor memory/concentration Dizziness Symptoms can linger for several days, and much longer in some cases. Headaches, fatigue, irritability, fogginess, and memory problems are common, but not the only symptoms. Sometimes there can be neck stiffness from the blow and balance problems. What Do You Do If You Sustain a Concussion? Typically, low-grade concussions do not require extensive medical treatment. Because of the potential for serious complications, they must be monitored closely and often after the event. If urgent medical attention is needed, you want it to be close by. You should be evaluated immediately after the concussion and closely monitored in case symptoms worsen. If there is symptoms worsen (such as lethargy, headache, vomiting, stiff neck, slurred speech, and confusion) then immediate medical care is required. If you were not evaluated at the event, you should contact a physician or seek an emergency room evaluation. It is extremely important not to return an athlete to play before they have fully recovered from a concussion. There is not one system for grading concussions, but doctors generally check all of your senses and ask questions to check your memory and how you respond. Sometimes a CT scan or MRI is taken to make sure your brain is not bruised or bleeding. These scans are non-invasive and give a much clearer picture of what is going on inside your skull. Rest is the best way to recover from a concussion, but here are some tips to help you get better: Get plenty of sleep at night, and take it easy during the day. Avoid alcohol and illegal drugs. Do not take any other medicine unless your doctor says it is okay. Avoid activities that are physically or mentally demanding (including housework, exercise, schoolwork, video games, or using the computer). Ask your doctor when it’s okay for you to drive a car, ride a bike, or operate machinery. Use ice or a cold pack on any swelling for 10 to 20 minutes at a time. Put a thin cloth between the ice and your skin. Use pain medicine as directed. Your doctor may give you a prescription for pain medicine or recommend you use a pain medicine that you can buy without a prescription. Second Impact Syndrome A second concussion sustained before the first one has fully healed is called second impact syndrome (SIS). SIS occurs when the brain losses its ability to control blood flow and the pressure builds up to unsafe levels and damages the brain. When SIS occurs, it can be lifethreatening as the brain may swell rapidly and require emergency surgery. While SIS is rare, it has lead to rapid, severe and permanent brain injury and many do not survive. All of this is preventable by not returning to sport too soon, which is why it is so important to allow a young athlete to fully recover before returning to sport. Return to Sport After a Concussion In sports, every state is now coming up with their own return-to-play rules. Concussions are unique to the individual, and each person will recover differently. No one can accurately predict when concussion symptoms will clear up, so it’s important to take things slowly. A doctor must always determine when an athlete is ready to return to play. A gradual, incremental approach is recommended based on recommendations from the Zurich international panel of concussion experts. Before starting a return to play protocol, an athlete must be free from symptoms and not have any memory or concentration issues. After that, the Zurich panel recommends the following steps: Day 1: light aerobic exercise (walking, swimming, or stationary cycling) keeping exercise heart rate less than 70% of maximum predicted heart rate. No resistance training Day 2: sport-specific exercise, any activities that incorporate sport-specific skills (skating in hockey, running in soccer, etc). No head impact activities. Day 3: non-contact training drills Day 4: full contact practice, participate in normal practice activities Day 5: return to competition There should be approximately 24 hours between each step and the athlete must be free of concussion symptoms after each step. If concussion symptoms return, the athlete must rest (no exercising) until all symptoms have gone away then return to the previous level. There does not seem to be a magic number of concussions that force an athlete to “retire” from sports. This is determined by the severity of the concussions and how long it takes for symptoms to clear. The best method for determining recovery from a sports concussion is through a thorough medical assessment of cognitive abilities, balance and other possible symptoms. , While neurological examinations and CT scans or MRIs are relatively insensitive in detecting a sports concussion, tasks such as memory, concentration, reaction time, and how quickly you think are the most sensitive measures of a concussion. The best method for measuring the effects of sports concussion is through baseline testing BEFORE an athlete is concussed so a doctor can compare the results of the same athlete. This is why baseline testing has become so important to most sports concussion programs. Baseline tests such as ImPACT, Axon Sports, Concussion Vital Signs, and HeadMinder have been developed specifically for this purpose and the testing is simple and easy to understand. The results give a doctor an objective measure of cognition, allowing for a more accurate diagnosis and treatment plan. Concussion Statistics in High School Sports There are between an estimated 1.6 and 3.8 million sports-related concussions in the United States every year,1, 2 leading The Centers for Disease Control (C.D.C.) to conclude that sports concussions in the United States have reached an "epidemic level." A 2011 study8 of U.S. high schools with at least one athletic trainer on staff found that concussions accounted for nearly 15% of all sports-related injuries reported to ATs and which resulted in a loss of at least one day of play. According to the C. D.C., 6.5% of all sports-related emergency room visits (173,285) involved a traumatic brain injury, including concussion. Football Players Most at Risk At least one player sustains a mild concussion in nearly every American football game. According to research by The New York Times, at least 50 youth football players (high school or younger) from 20 different states have died or sustained serious head injuries on the field since 1997. Anecdotal evidence from athletic trainers suggests that only about 5% of high school players suffer a concussion each season, but formal studies surveying players suggest the number is much higher, with close to 50% saying they have experienced concussion symptoms and fully one-third reporting two or more concussions in a single season. One study estimates that the likelihood of an athlete in a contact sport experiencing a concussion is as high as 20% per season. According to the National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research, there were 5 catastrophic spinal cord injuries in high school football in 2010. 67.8% of all catastrophic injuries in football since 1977 are from tackling. According to a study reported in the July 2007 issue of The American Journal of Sports Medicine: o Football players suffer the most brain injuries of any sport; o An unacceptably high percentage (39%) of high school and collegiate football players suffering catastrophic head injuries (death, nonfatal but causing permanent neurologic functional disability, and serious injury but leaving no permanent functional disability) during the period 1989 to 2002 were still playing with neurologic symptoms at the time of the catastrophic event. Are Girls More Susceptible? While a study published in the Journal of Athletic Training3 suggested that girls were much more susceptible to concussions in sports like soccer and basketball than boys. The reason for the higher concussion rate for girls are unknown, although some have theorized that female athletes have weaker neck muscles and a small head mass than male athletes5 or that male athletes are more reluctant to report concussions for fear of being removed from competition, which may result in the well-documented underestimation of the incidence of concussion among boys.6 Multiple concussions 16.8% of high school athletes suffering a concussion had previously suffered a sportrelated concussion, either that season or in a previous season More than 20% of concussions in boys' and girls' soccer and basketball were repeat concussions. Once an athlete has suffered an initial concussion, his or her chances of a second one are 3 to 6 times greater than an athlete who has never sustained a concussion. Slightly more than a third of high school players in one recent survey who reported two or more concussions within the same school year.8 High school athletes who suffer 3 or more concussions are at increased risk of experiencing loss of consciousness (8-fold greater risk), anterograde/post-traumatic amnesia/PTA (reduced ability to form new memories after a brain injury) (5.5-fold greater risk), and confusion (5.1-fold greater risk) after a subsequent concussion. Children who are seen in a hospital emergency room for a head injury, concussion, skull fracture or intracranial injury) are more than twice as likely to sustain a subsequent head injury of similar type within 12 months as are children seeking care for an injury not related to the head, regardless of their age. Athletic Trainer Attempts Research Sandra Black, an ATC from Texas Tech University, examined a possible relationship between neck strength and concussions in Division I Football players in her Master’s Thesis. Limited resources and subjects made it difficult for her to come up with statistically significant results, but the body of evidence that she provides still makes an obvious case for the implementation of direct neck strength training. Her study examined 12 athletes who sustained concussions and 12 who had not. She then went back and compared their strength training records to see if there were any differences in strength. There were no differences, but it’s clear that the study has plenty of flaws. Most obvious is the fact that the 12 who had no concussions may not have been hit either. We don’t know. Still, by digging into the relevant literature, she draws the conclusion that strengthening the neck may be helpful in reducing the forces encountered during a hit. Again, we are not claiming that the one-time, big hit you see on SportsCenter is going to be nullified by a strong neck. These major blows are like a helmet to the knee – there’s pretty much nothing that can prepare you for it. We are more worried about the sub-concussive forces encountered on just about every play - the small dings and hits that players get when helmets are knocked against each other or against the ground. The player may not get knocked out or feel disoriented, but these hits can build up over time and cause long-term damage. If we can raise the bar on the number of sub-concussive blows an athlete can sustain, we may be able to prevent serious problems. The research that Sandra Black conducted supports this theory. Football Helmet Ratings from Virginia Tech Researchers at Virginia Tech have produced the first brandby-brand, model-by-model ranking for the likely concussion resistance of helmets. They created a star-rating system modeled on crash safety rankings for automobiles. These rankings clearly identify the best and worst helmets. Virginia Tech researchers give high marks to the following helmets: Riddell Revo Speed Riddell Revolution Riddell Revolution IQ Schutt Ion 4D Schutt DNA Xenith X1. The Virginia Tech researchers give medium grades to the following helmets: Schutt Air XP Schutt Air Advantage The Virginia Tech rankings warn players not to wear these helmets: Riddell VSR4 Adams A2000 None of the research was funded by a helmet company or any other organization with the potential to profit from the results. Interestingly, the report found absolutely no correlation between cost and ratings. In fact, the lowest-ranked helmet, the Adams A2000, costs $200, while the four-star Schutt DNA retails for $170. The DNA looks like the best value on the market right now -- nearly as good in safety ranking as the top-rated Riddell Speed, but costs about $75 less. This can make a huge difference when purchasing a large number of helmets for a team. Virginia Tech's current findings pertain to pro, college and prep football, but they have already started to study helmets for youth football. No results are available yet. Studying hockey and lacrosse helmets would probably produce similar results and differences, but we have not found any studies or rankings yet. In the 1960’s, football helmets were vastly different than what is available today. In fact, skull fractures were very common in football back then. Today, with upgraded helmets, skull fractures are very rare, but we still see plenty of concussions and neck injuries. To help regulate helmet standards in the 60’s, the National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment (NOCSAE), an independent organization, was formed. Today, the NOCSAE sticker MUST be put on all helmets allowed to be worn in the NFL. Helmet manufacturers must be granted approval from NOCSAE after going through their "severity index" of what happens in a linear impact. What’s funny is that ALL helmets on the market get to put the NOCSAE seal on them. To receive the NOCSAE seal, a helmet must score no more than 1200 on their index. ALL helmets on the market in the past decade have passed the NOCSAE test as long as they score below 1200. "Because every helmet always passes the NOCSAE test, in effect that test says nothing," says Stefen Duma the Virginia Tech engineer who led the rankings project. "An Adams at a severity index of 1150 and a Riddell Speed at an index of 400 offer vastly different protection. But to the NOCSAE seal system, they're the same. NOCSAE ranks all helmets as equal, and that is just not true." NOCSAE makes money by licensing the use of their logo. That, and their inadequate rating scale, discounts the value of what having their logo on a helmet means. This should not be the only factor used when deciding which helmet to purchase for an athlete. Researchers at Virginia Tech seem to be taking the same pro-active approach to prevention that we are taking. "There will never be perfect information, but we know enough to do something today," Duma says. He went on to note that many kinds of safety advances that were initially controversial, and are now considered great ideas -- seat belts and air bags, warnings about cigarettes and cancer -- were put in motion long before scientific certainty. If it was unethical to offer guidance absent scientific certainty, the National Institutes for Health, American Medical Association and the Centers for Disease Control would rarely say anything. Again, we are not claiming that concussions and neck injuries can be eliminated, but it seems there is enough information available for us to move forward with preventive measures. While these preventative measures may not be “scientifically validated” by research yet, we feel there is an ethical responsibility to at least present pro-active options for keeping young athletes safe. More research needs to be done in this area, and we hope that it takes place before more kids are severely injured or dead. 1. Halstead M, Walter K. Clinical Report - Sport-Related Concussion in Children and Adolescents, Pediatrics 2010; 126(3): 597-615 at n. 22, 23 (citing studies); 2. Lincoln A, Caswell S, Almquist J, Dunn R, Norris J, Hinton R. Trends in Concussion Incidence in High School Sports: A Prospective 11-Year Study. Am. J Sports Med. 30(10) (2011), accessed at http://ajs.sagepub.com/content/early/2011/01/29/0363546510392326.full.pdf+html 3. Gessel LM. Fields SK. Collins CL. Dick RW. Comstock RD. "Concussions among United States high school and collegiate athletes" J. Athl Train. 2007; 42(4): 495-503. 4. Lincoln A, Caswell S, Almquist J, Dunn R, Norris J, Hinton R. "Trends in Concussion Incidence in High School Sports: A Prospective 11-Year Study" Am. J. Sports Med. 2011; 30 (10), accessed January 31, 2011 @ http://ajs.sagepub.com/content/early/2011/01/29/0363546510392326.full.pdf+html. 5. Halstead M, Walter K. Clinical Report - Sport-Related Concussion in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics 2010; 126(3): 597-615 at n. 31, 32 6. Meehan W, d'Hemecourt P, Comstock D, High School Concussions in the 2008-2009 Academic Year: Mechanism, Symptoms, and Management. Am. J. Sports. Med. 2010; 38(12): 2405-2409 (accessed December 2, 2010 at http://ajs.sagepub.com/content/38/12/2405.abstract?etoc). 7. Meehan WP, d'Hemecourt P, Collins C, Comstock RD, Assessment and Management of Sport-Related Concussions in United States High Schools. Am. J. Sports Med. 2011;20(10)(published online on October 3, 2011 ahead of print) as dol:10.1177/0363546511423503 (accessed October 3, 2011). Much of the research compiled here was taken from www.momsteam.com, a great site helping to increase the awareness of concussions.