Children's Understanding of the Concept of Dissent: Mapping Prior

advertisement

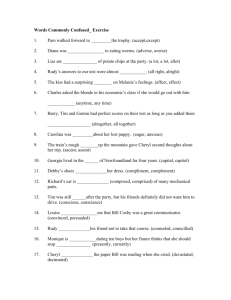

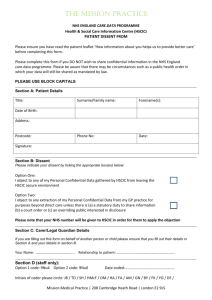

Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent: Mapping Prior Knowledge1 Andrew S. Hughes, Alan Sears, Kim Bourgeois, Barbara Corbett, Barbara Hillman and Neyda Long University of New Brunswick, Canada Corresponding Author: Dr. Andrew S. Hughes Faculty of Education University of New Brunswick Fredericton, N.B. Canada E3B 6E3 Telephone: (506) 453-5163 e-mail: hughesa@unb.ca 1 This work has been supported, in part, by a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 2 ABSTRACT Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent: Mapping Prior Knowledge This paper presents findings from a program of research concerned with mapping children’s and young people’s understanding of core principles of life in democratic societies. In this case the focus is upon the concept of dissent. The work emanates from a concern that while tacit recognition is often given to the need to appreciate the prior knowledge that children bring with them to the learning situation, there has been little systematic work in the field of citizenship education addressing the issue. Data were generated using a phenomenographic research method aimed at identifying the qualitatively different ways in which individuals understand a phenomenon. The resulting analysis shows children and young people to construe the concept of dissent in terms of three major themes: deference, dialog and defiance. Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 3 Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent: Mapping Prior Knowledge In this paper we present findings from work concerned with mapping children’s and young people’s conceptions of a constellation of ideas that shape life in societies committed to democratic principles. Our interest is in ideas that shape and give direction to civil and civilized being. These are ideas such as freedom, dissent, diversity, due process, equity and equality, human rights, privacy, property, the rule of law and tolerance; ideas shown to be among common principles of democracy across societies even when the institutions devised to advance the principles differ (Beetham 1994; Simon 1996). Broadly speaking, we are concerned with how children and young people construe these ideas and how their understandings grow. Here, we report findings related to children’s understanding of the concept of dissent. Prior Knowledge One of the commonplaces of teaching is that we should begin with what the learner already knows. Certainly, we know that there is a strong relationship between this prior knowledge and subsequent performance, as evidenced by a synthesis of some 183 studies by Dochy, Segers & Buehl (1999). Quite simply, the “kinds and amounts of knowledge one has before encountering a given topic . . . affect how one constructs Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 4 meaning” (Leinhardt, 1992, p.21). As a practical implication, learning theorists say: “First, teachers must be familiar with, respect and actively use students’ prior knowledge as they teach” (Newmann, Marks & Gamoran, 1996, p.285). It is a fundamental tenet of a constructivist approach to teaching and learning (DeCorte, 1990). In principle, the process is quite straightforward. It seeks to apply Ausubel’s dictum that “the most important single factor influencing learning is what the learner already knows. Ascertain this and teach him accordingly” (1968, p.vi). In practice, however, the teacher faces two daunting tasks. The first is to ascertain what the student already knows, or more precisely, what a whole class or several classes of students already know. The second is to determine what is implied by the term ‘accordingly.’ The research literature approaches the concept of prior knowledge from a variety of perspectives, each with its own terminology. There is reference to current knowledge and preknowledge, permanent stored knowledge and the prior knowledge state, archival memory, experiential knowledge, background knowledge and personal knowledge; there is a literature on misconceptions, naïve understandings and primitives, preunderstanding, PKR (pieces of knowledge and reasoning), students’ descriptive and explanatory systems, children’s science, and alternative frameworks (Byrnes & Torney-Purta, 1995; Hill, 1995; Minstrell & Hunt, 1991; Gilbert, Osborne & Fensham, 1982; Hewson & Hewson, 1982). What they all possess in common is the view of prior knowledge as a launch pad to future learning. The knowledge distilled from previous experiences “are the hooks upon which new learning is hung [with] previous experiences . . . the filters Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 5 through which we interpret new information” (Rakow, 1992, p.18). Certainly, we know that our students do not come to us as platonic blank slates. Both intuitively and empirically we know that they bring a rich array of experiences that have shaped their being and their belief. Witness the nascent theory of justice among the smallest of children who protest that the actions of their playmates are “no fair.” Scarcely grammatical in their utterance, they have begun for forge a sense of what is fair and unfair, what is just and unjust. The problem, though, is that while teachers and parents have observed the phenomenon of this early shaping of ideas, there has been no systematic attempt to map children’s conceptions of the core ideas of democratic living, in a manner that would be of value in planned teaching and learning. The Topography of Dissent In this research, the focus was upon children’s and young people’s understanding(s) of the concept of dissent. This is one of the concepts that lie at the core of the democratic spirit. It is generally viewed as a dynamic force that produces growth in every aspect of human endeavor. Riga (1995) argues that dissent must be tolerated, even institutionalized (as in parliamentary democracies with ‘loyal oppositions’) because “it might truly reflect a dimension of truth which today is hidden from us, but which tomorrow we may see more clearly” (p.71). In the aftermath of the Civil War, Frederick Douglass proclaimed that “those who profess to favor freedom, and yet deprecate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing the ground. They want rain without Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 6 thunder . . . they want the ocean without the roar of its waters.” Dissent is a force that positively shapes both science and art; in political and civil society, it informs the debates about how we govern ourselves, whether locally, nationally or globally. Among the central tenets of democracy is the belief that the just powers of the government derive from ‘the consent of the governed.’ The related notions of ‘popular consent’ and ‘sovereignty of the people’ imply that citizens must participate in the shaping of society, not just by providing and withholding consent, but through active and vigorous dissent when called for. Of course, the instruments of participation are varied: voting and lobbying, campaigning, marches and sit-ins, freedom rides and hunger strikes, protests, demonstrations and disruptions; there are even “the weapons of the weak” – “foot-dragging, desertion, dissimulation, false compliance, pilfering and feigned ignorance” (Scott, 1985, p.xvi). To be skillful citizens, young people need to learn this instrumentation of participation, much of it concerned with the expression of the dissenting viewpoint; but to be mindful citizens, they also need to learn something of its spirit. But where does it come from? How is it learned? How can it be nurtured? Of course, there is a long tradition of research examining the nature of children’s thinking on a range of social issues. Such work has clearly established that children’s views of the world become more sophisticated, complex, abstract, articulate and assertive as they grow older. (Turiel, (1983); Kohlberg, 1981; Piaget, 1973.) Such conclusions address the form of thinking displayed by children but say little about the content of the thinking itself. They can tell a teacher how the character of children’s thinking might Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 7 develop but say nothing about what they are actually thinking. What such work does not address is the children’s prior knowledge. Mapping Conceptions The technical challenge in the research has been to find ways of capturing and portraying students’ prior understandings. For most people, and particularly for children, direct as questioning such as by asking “what do you understand by the term freedom, or dissent, or equity” does not provide much in the way of rich information (Turiel, 1983, p.87). All people, including children, are likely to know much more than they can articulate in abstract terms; hence their tendency to represent their views in terms of instances and exemplars. Even direct observation seems limited in its potential. For example, in our community, just recently, students in a school found themselves threatened by an administrator for signing a petition; in another, school administrators removed notices announcing the availability of support services for gay students. Both situations would appear to be fertile ground for uncovering children’s conceptions of some core democratic ideas. The problem, though, is that such naturally occurring events are not always amenable to systematic study. Indeed, such events are anxiety ridden and potentially traumatic and school administrators, teachers, parents and students can view researchers as unwelcome intruders, more likely to inflame the situation than to illuminate it. Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 8 In our quest to find a mechanism to capture children’s and young people’s conceptions of the ideas of democracy, we have gravitated increasingly toward a phenomenographic procedure. Phenomenography is a research specialization “aimed at the mapping of the qualitatively different ways in which people experience, conceptualise, perceive, and understand various aspects of, and various phenomena in the world around them” (Marton, 1988, pp. 178-179). The approach centers on the phenomenographic interview with “the interviewer responsible for trying to see the phenomenon as it is seen by the interviewee” (Bruce, 1994, p.50). ‘Seeing,’ of course, is a metaphor for how students organize and structure their ideas. The objective of the research is to construct an image of students’ cognitive schemata. Since we cannot observe these structures directly, we infer them (Torney-Purta, 1991). Within the framework of the phenomenographic interview, we make use of a semi-projective technique. The semi-projective method is an extension of projective methods used in personality assessment but the “stimulus content is more structured and culturally patterned.” (Greenstein & Tarrow, 1970, p. 501) In this case, students were asked to “project” themselves into an authentic situation dealing with the issue of school dress codes. Here they used “think aloud” procedures to describe and explain the behavior of the actors in the situation, and to imagine what their own responses would have been. Students may be unrestrained but the stimulus itself possesses a subject matter that serves to focus attention. In this research, the stimulus consisted of a storyboard of an actual event. The task of the interviewer was to probe the “internal and external horizons of the Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 9 interviewee’s experience” (Bruce, p. 50). The interviewer seeks out the elements that are the focus of attention, is sensitive to examples, comparisons and analogies, and encourages exploration and elaboration of areas of confusion or paradox. The phenomenographic interviewer probes both percepts and concepts; what is seen and what is made of what is seen. In one of the schools in the study, the characters in the story are shown vandalizing school property. In the other three, the story concludes with the characters continuing to violate the original school policy. The latter ending was provided to accommodate concerns that the story would imply vandalism to be a legitimate action in situations where there is disagreement. In each interview, the objective was to discern the elements that shaped the way the episode was experienced. The findings confirm the general pattern of a wide range of phenomenographic work. That is, the number and configuration of elements that reveal themselves in each individual’s responses varies but is not unlimited. It is quite clear that there is “a limited number of qualitatively different ways of experiencing a phenomenon” (Marton, 1996, p. 183). The phenomenographic analysis proceeds from the identification of the elements that matter to each individual to the mapping of elements that are common to several individuals. In the first instance, individual concept maps were generated based on verbatim interview transcripts. Comparison across the individual cases sought recurring elements; and it was these recurring elements that were named phenomenographic themes. It is the existence of such themes that allows us to characterize ways of Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 10 experiencing an episode in terms of a finite number of categories. The practical implication for teaching is that this permits us to recognize and respect the individual integrity of each one of our students but also admits the common though not uniform countenance in how they experience the world. Fundamentally, it permits us to think in terms of how children typically make sense of their experience. The objective here is not to obliterate differences among children in some sort of futile attempt to characterize “a typical child;” rather, it is to identify the range of conceptions likely to be held. The data we report here come from interviews with 54 children in grades 2, 6, 8, and 12 (the modal ages were 7, 11, 13 and 17). They were from four different schools located in small towns (population 50,000). Children were interviewed individually by their own teachers who were also trained members of the research group. In each instance, the interviewer related an occurrence to the child who followed along using a storyboard (Figure 1). The events portrayed are authentic in the sense of actually having happened in one of the schools. It was a plausible event in the life-world of the children being interviewed. What is important is that the episode evoked both a visceral and a cognitive response. It provided children with the opportunity to project themselves into a situation thereby revealing the guiding principles that shape their reactions and responses. The choice of the particular episode of the school dress code was problematic for the researchers. As always, there is the issue of whether a school situation can be truly analogous of broader social and political issues, and there was the need for something that could be addressed by children of widely varying ages (7 to 17). In the Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 11 end, we committed to this particular episode because pilot-testing revealed that it would engage students of all age levels, and second, because it showed that children were aware of analogs with laws and government policies that can be the subject of dissenting viewpoints within society. Insert Figure 1 About Here FINDINGS Our analysis of the verbatim transcripts and the concept maps constructed for individual children reveals a set of overlapping conceptual lenses through which the children and young people in the study make sense of this particular episode. All of these lenses or themes are present to a greater or lesser degree in the conceptions of children at all grade levels except for the youngest children where a single perspective dominates. We have labeled the themes deference, dialog and defiance. Each of the themes contains sub-elements as outlined below. What the results show is that the children and young people in this study construed the concept of dissent in a number of qualitatively distinct ways; indeed, individual children were quite capable of employing varying, different and sometimes competing conceptions of the concept at the same time. Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 12 Insert Table 1 about here Deference The dominant reaction of the younger children to the ‘shorts’ episode can be encapsulated in the concept of deference. Every single one of the seven year-olds (n = 16) indicated that they personally would have obeyed the school rule and that they felt it was wrong for Cindy and Thomas not to do likewise. For them, the rules, and perhaps more importantly, the school principal are to be obeyed – this they view as a matter of respect. Indeed, for this group, respect manifests itself in an unquestioning obedience. None of these predominantly seven year olds sought to question the legitimacy of neither the rule itself nor the right of the school authorities to impose it. At the same time, they attributed an innocent interpretation to the motives for Cindy’s and Thomas’s actions. Interviewer: Why do you think they wore shorts to school in the first place? Various Students: They were new kids and didn’t know that rule. Their mom made them. It was summer. They had gym. Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 13 Interviewer: Why did they wear shorts again after being sent home? Students: Maybe they forgot. (Suggested by more than half of the students) A few said that “maybe they didn’t like school and wanted to be sent home again.” Several suggested that if anything like this ever happened to them they would tell their mom (always mom, never dad or even parents). Certainly, none of the grade 2 students saw the wearing of the shorts the second time as any sort of political statement; certainly, it could in no way be construed as a matter of freedom of expression for the students. It was not an act of dissent in the sense of the expression of a contrary viewpoint. If these students feel any sense of concern or reservation about the school rule or the treatment of the students involved, their dissenting feelings are suppressed within a framework emphasizing obedience and respect. The 11 year-olds also showed a highly deferential disposition in their interpretation and assessment of the episode. They also would conform to the school rule without challenging it in any way (13 out of 14 students) but their reasoning is somewhat different from the seven year-olds. Interviewer: What would you have done if you were in the same situation? Student: Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 14 Ummm . . . I would have come back wearing pants like I was supposed to. Interviewer: Why wouldn’t you break the rule? Student: Because I’m not one of those kids. Interviewer: Those kids? Here emerged a typical line of thinking. The students inferred that Cindy and Thomas were ‘bad’ kids – they were referred to as trouble-makers, inattentive, inclined to fighting, swearing, shop-lifting – all somehow inferred from the episode with the shorts. Furthermore, these 11 year-olds showed a fear of implications that extended well beyond the episode itself. “Like, you’re in the principal’s office and he calls your parents and you get in trouble at home.” Or, “you get a bad reputation; like you’re always breaking the rules and doing drugs.” For these 11 year-olds, the result of the whole episode is that “you get a hard time” from the principal, teachers and even parents. The best alternative is to “just come back to school wearing jeans or something . . . [Why?] ‘Cause I didn’t want to get into trouble again.” There is a surface compliance here; a deferential disposition but it is a deference of expedience. The authority figures are to be obeyed not because they are right but because the ensuing “hassle is not worth it.” Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 15 Dialog With just a few of the 11 year olds, there was a hint that that rule itself was considered “stupid.” When probed about the meaning of stupid, students tended to explain their conclusion in terms of the rule being “unfair.” But the concern was neither strong nor pervasive. It was mentioned only by a few students and was not central to the concerns expressed by those students. Even for the 13 year-olds, deference to authority and obeying the rules was the accepted norm. Although students expressed the view that the rule itself “sucks” or was “stupid” or was “not fair,” they indicated that they would “go along with it.” But among this group there begins to emerge a sense that it is legitimate to question authority, to question rules but only through acceptable means. For these students, “acceptable means” require some measure of discussion. “They could have talked the rule over with him . . . tried to convince him to change his mind . . . or maybe they could have talked with their parents.” Some suggested that they could talk with teachers or “write him a letter, or write to the school board.” None of the students interviewed said that they could envisage themselves spray painting graffiti on the school and they expressed disapproval of Cindy’s and Thomas’s actions though they could sympathize with their actions: “They thought maybe . . . it would make him like realize that the no shorts thing was really like . . . stupid or something.” They did it “to show the way they feel.” “Because they were very angry.” “To make their point.” But several saw the spray painting as an act of revenge “just to get back at him.” The spray painting was Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 16 being “bad,” as was the wearing of the shorts in the first instance. “They were trying to be disobedient,” “ . . . to be rebellious,” “just to be bad!” While there is a strong theme of deference in the general reaction of the 13 yearolds, they do display a sense that rules can be unfair and that they may be challenged. For most, though, there is a right way of challenging and this is through “dialog.” Implicit in their talk seems to be the view that if only there is a reasonable dialog among the interested parties, then there will inevitably be a mutually acceptable resolution of the issue. There was no hint, however, of how to proceed if a resolution was not achieved. These students are clearly aware of non-compliance and defiance but they are notions with which they are not at all comfortable. They might contemplate them – “I would think about it, but I wouldn’t do it.” There seems to be a latent sense of non-compliance and/or defiance as just “not being the right thing to do.” Defiance The theme of defiance, in the sense of overt public disagreement with authority emerges as an important theme only with the 17 year-olds. For these students, defiance represents a legitimate avenue of expression, but only when discussion and dialog have not achieved a satisfactory outcome. Unlike the younger children who see Cindy and Thomas as bad and rebellious, this group describes them as “standing up for themselves,” and “fighting for what they believed was right.” What was right was interpreted as rules that “make sense” and “are applied equally.” Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 17 “They figured, you know, maybe the dress code was being unfair. They couldn’t see no reason why they weren’t allowed to wear shorts.” And, If their shorts were too short, it doesn’t make much sense ‘cause she has a skirt and that’s just as short as their shorts.” (The ‘she’ here is the female student in the first panel in Figure 1. The younger students had omitted any mention of her.) For the 17 year-olds, the issues raised in the storyboard are neither frivolous nor unreasonable. The conception of dialog, for this group, is also somewhat more sophisticated. Almost all of them see a discussion at the school level as the start of a process of negotiation in which they are neither powerless nor helpless. The enlistment of the aid of parents or teachers is not simply an upward delegation of responsibility as it might be for the younger students. It is a clear recognition that “. . . adults get more response to problems like that than kids would.” Furthermore, they show a belief that it would be advantageous to act as part of a group. There is a sense that group solidarity lends a measure of protection. One student explicitly mentioned that “there is power in numbers” and another surmises “maybe if, not only them, but they got everybody in the school to wear these shorts, then the principal is not going to suspend every person in the whole school.” In all of this, nevertheless, there is a generally deferential and respectful disposition. Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 18 It could be taken wrong that they came with shorts on in the first place. Instead of just dropping in with the shorts on or whatever, they should have gone to the principal and they knew it was a school rule so they should have gone to him and talked about it first and seen what kind of compromise he would have come up with. So, I guess they took the wrong action first of all. In their comments on what the students in the story might do, these 17 year-olds explicitly referred to discussion, public meetings, letter writing to authorities and to the media, posters and even walkouts. They showed an awareness of a range of measures: legal and illegal, violent and non-violent. They were even able to identify situations in their schools and elsewhere where they thought there had been an abuse of authority by administrators and teachers. They could understand how others would be provoked to act but did not see themselves as generally disposed to taking action – “I just can’t see myself doing anything.” Conclusion The general representation of children’s and young people’s responses to this single episode consists of themes of deference, dialog and defiance. Elements of all three themes were found in the reactions of students at all age levels except for the youngest children. What varied was the relative emphasis. With the younger children there was clearly an emphasis upon unquestioning deference with just a whisper of the other Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 19 themes. With the 11 and 13 year-olds there was a simplistic faith in dialog but within a generally deferential framework. With the older adolescents there was an emerging sense of a purposeful and strategic dialog, still deferential in orientation but with the possibility of defiance to provide leverage in dispute resolution. The pattern is clearly one of development from the naïve toward the more sophisticated. With the younger children there was a relatively small number of elements at play in the situation, each one minimally related to others in a sort of splendid isolation. With age, more elements inject themselves into the situation, often interacting in complex ways; sometimes providing contradictory and conflicting perspectives. Although implicit rather than explicit, the students clearly confront competing values. There is reflection on the meaning of respect, disagreement, fairness, personal security, harmonious relationships, even violence against property and persons, and of course, which of them are to be accorded precedence in real situations. What is consequential in the findings is not the form of the reasoning, however; it is, rather, in the identification of those aspects of understanding of the concept of dissent that shape children’s and young people’s intellectual schemata: for younger children an orientation that emphasizes respect and obedience; for younger adolescents a focus on dialog and discussion; for older adolescents a faith in dialog but a recognition of the need for mechanisms of reconciliation when dialog fails. In each instance, the prior knowledge constitutes a platform from which teachers and students can launch a further Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 20 exploration of the idea, assessing the legitimacy and efficacy not just of the theoretical abstraction of dissent but of its concrete manifestations in real situations. IMPLICATIONS FOR TEACHING AND LEARNING If citizen participation in the democratic enterprise is construed, at least in part, as the communication of consent and/or dissent, then the parameters of the concept employed by the citizenry will shape the character of participation. The portrayal of these parameters as dimensions of the cognitive schemata generated in this work helps establish something of the terrain. Of course, the children’s schemata that we have described constitute “naïve theories” in the sense conveyed by Torney-Purta (1991). They are not fully developed as they might be in the literature of political philosophy or even as they might be conceived by a thoughtful adult. They are, nevertheless, what the students bring with them to the learning encounter. They constitute the children’s prior knowledge. They represent the base upon which any future understanding must be constructed. In order to extend and refine, or perhaps reshape and reform, their conceptual understandings, learners have to engage in an assessment of the adequacy of their current intellectual schemata. Where there is a conception of dissent-as-deference, children need to assess the core propositions of the position. Is it indeed the case that people who challenge existing authority are simply “bad people,” that they are “just trouble-makers?” And it should be done in the context of specific, concrete situations. In any country, Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 21 children can examine their own national histories. Do they see the great reformers of their societies as trouble-makers? Is this a reasonable way to construe Washington and Jefferson? Or what about Fidel Castro or Ho Chi Minh? In what ways are they similar to or different from the protesters and picketers who confronted political leaders at the meetings of the World Trade Organization at the “Battle of Seattle” in 1999? In the dissent-as-dialog orientation, children exude a strong faith in the power of dialog. Can they assess whether such a faith is warranted? Does the history of the labor movement or the women’s movement, Sakharov’s Soviet Union or Biko’s South Africa, confirm or challenge their conceptions. Of course, in order to find out, students have to learn the details of each of the cases that teachers suggest or select. They have to learn “the facts.” The adequacy of their “concepts” is tested in the crucible of actual situations, either vicarious or direct. Where there is an image of dissent-as-defiance, children need to engage the ideas of Martin Luther King and Mahatma Gandhi, and also those of Jomo Kenyetta and Nelson Mandela. They need to come face to face with Thoreau and to explore his claim that from time to time it may be “. . . one’s duty to obey that ‘higher law’ and deliberately violate the law of the land . . . even to the point of going to jail” (1967, p. 19). When students suggest that “some issues are just not worth the hassle,” can they ask Burke what he meant when he said that “the only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing”? Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 22 By identifying the major features in the terrain of children’s understanding of the core ideas of democracy, we can help provide teachers and learners with a map from which they might orient themselves, from which they can get their bearings. In the findings reported here, we suggest that the major features on the landscape of the concept of dissent among children and young people consist of deference, dialog and defiance, often viewed in the naïve framework of children as discrete and competing alternatives rather than as elements of a complementary and synergistic whole. Being aware of the dimensions of children’s prior knowledge can help us, as teachers, to chart both the starting points for new learning and the course ahead. Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 23 REFERENCES Ausubel, D. P. (1968) Educational psychology: a cognitive view. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Beetham, D. (1994) Defining and measuring democracy. London: Sage. Bruce, C. (1994) Reflections on the experience of the phenomenographic interview. In Ballantyne, R.,& Bruce, C. Phenomenography: Philosophy and Practice. Brisbane: Queensland University of Technology. Byrnes, J.P., & Torney-Purta, J.V. (1995) Naïve theories and decision-making as part of higher order thinking in social studies. Theory and Research in Social Education, 23 (3), 269-277. DeCorte, E. (1990) Towards powerful learning environments for the acquisition of problem-solving skills. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 5 (1), 519. Dochy, F., Segers, M., & Buehl, M.M. (1999) The relation between assessment practices and outcomes of studies: the case of research on prior knowledge. Review of Educational Research, 68 (2), 145-186. Gilbert, J.K., Osborne, R., & Fensham, P. (1982) Children’s science and its consequences for teaching. Science Education, 66 (4), 623-633. Greenstein, F.I., & Tarrow, S. (1970) Political orientations of children: the use of a semi-projective technique in three nations. Beverly Hills: Sage. Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 24 Hewson, P.W., & Hewson, M.G. (1989) Analysis and use of a task for identifying conceptions of teaching science. Journal of Education for Teaching, 15 (3), 191209. Hill, S. (1995) Early literacy and diversity. Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 20 (1), 23-27. Kohlberg, L. (1981) The philosophy of moral development. San Francisco: Harper Row. Leinhardt, G. (1992) What research tells us about teaching. Educational Leadership, 49 (7), 20-25. Marton, F. (1988) Phenomenography: exploring different conceptions of reality. In D.M. Fetterman (Ed.), Qualitative approaches to evaluation in education. New York: Praeger. Minstrell, J., & Hunt, E. (1991) The development of a classroom based teaching system representing students’ knowledge structures and their processing of instruction. In Duit, R., Goldberg, F., & Neidderer, H. (Eds.), Proceedings of the Bremen International Workshop: Research in Physics Learning and Empirical Studies. Kiel: IPM. Newmann, F.M., Marks, H.M., & Gamoran, A. (1996) Authentic pedagogy and student performance. American Journal of Education, 104 (4), 280-312. Piaget, J. (1973) The moral judgment of the child. New York: Free Press. (Originally published, 1932) Rakow, S. (1992) Six steps to more meaning. Science Scope, 16 (2), 18-19. Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent Riga, P.J. (1995) The nature of truth and dissent. American Journal of Jurisprudence, 40, 71-78. Scott, J.C. (1985) Weapons of the weak: everyday forms of peasant resistance. New Haven: Yale University Press. Simon, J. (1996) Popular conceptions of democracy in post-communist Europe. University of Strathclyde Studies in Public Policy No. 292. Thoreau, H.D. As quoted by Harding, W. (1967) in an Introduction to The Variorum: Civil Disobedience. New York: Twayne Publishers. Torney-Purta, J.V. (1991) Schema theory and cognitive psychology: implications for social studies. Theory and Research in Social Education, 19 (2), 189-210. Turiel, E. (1983) The development of social knowledge: morality and convention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 25 Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent 26 Table 1 Children’s Understanding of the Concept of Dissent: Aspects of Awareness* (in percentages) Grade 2 (n=16) 7 Grade 6 (14) 11 Grade 8 (12) 13 Grade 12 (13) 17 1. Dissent-as-deference unquestioning obedience hollow compliance mindful compliance 100 0 100 57 8 92 0 15 0 0 0 15 2. Dissent-as-dialog seeking approval challenging unfairness negotiating a compromise 12 0 43 14 75 92 100 100 0 0 75 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 58 67 0 50 0 100 100 54 100 38 Grade: Modal Age: 3. Dissent-as-defiance right of appeal legal recourse illegal recourse non-violent recourse violent recourse This table shows children’s awareness of the ways in which dissent can manifest itself in social situations. It is not a measure of the extent to which they might advocate, support or condone such measures.