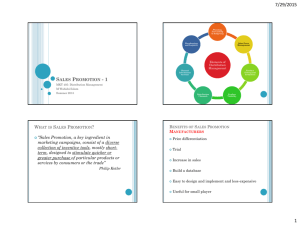

Summary - Ed Jennings

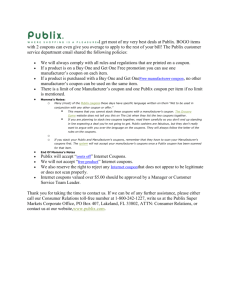

advertisement