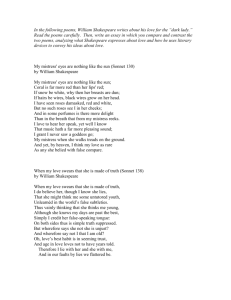

lyric impasse in shakespeare and catullus

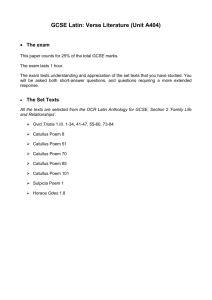

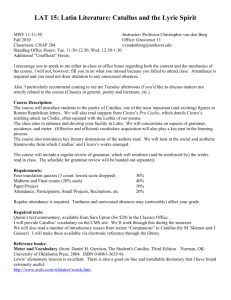

advertisement