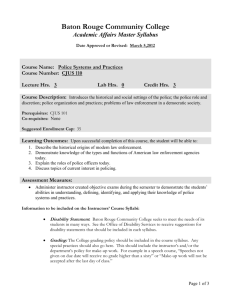

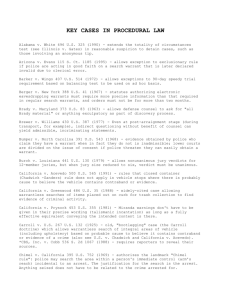

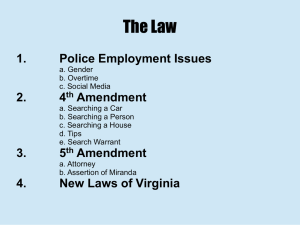

Criminal Procedure

advertisement