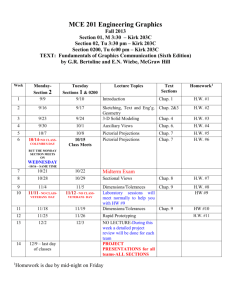

ii. 146

advertisement