file - The Society for the Study of French History

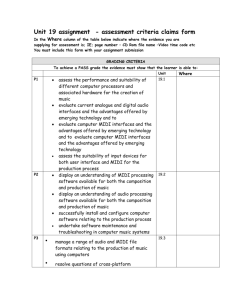

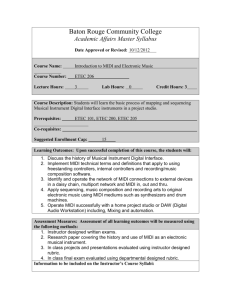

advertisement