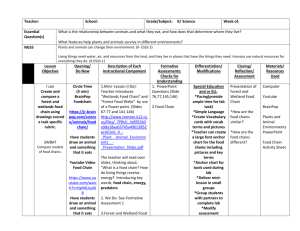

HVCN Innovations master document v14(2)

advertisement