Word - New York City Bar Association

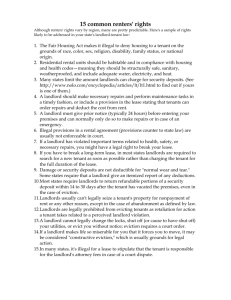

advertisement