The dangers of trusting Iconography

advertisement

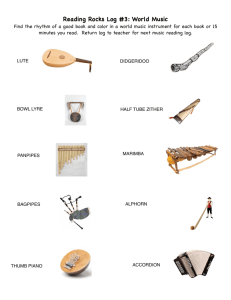

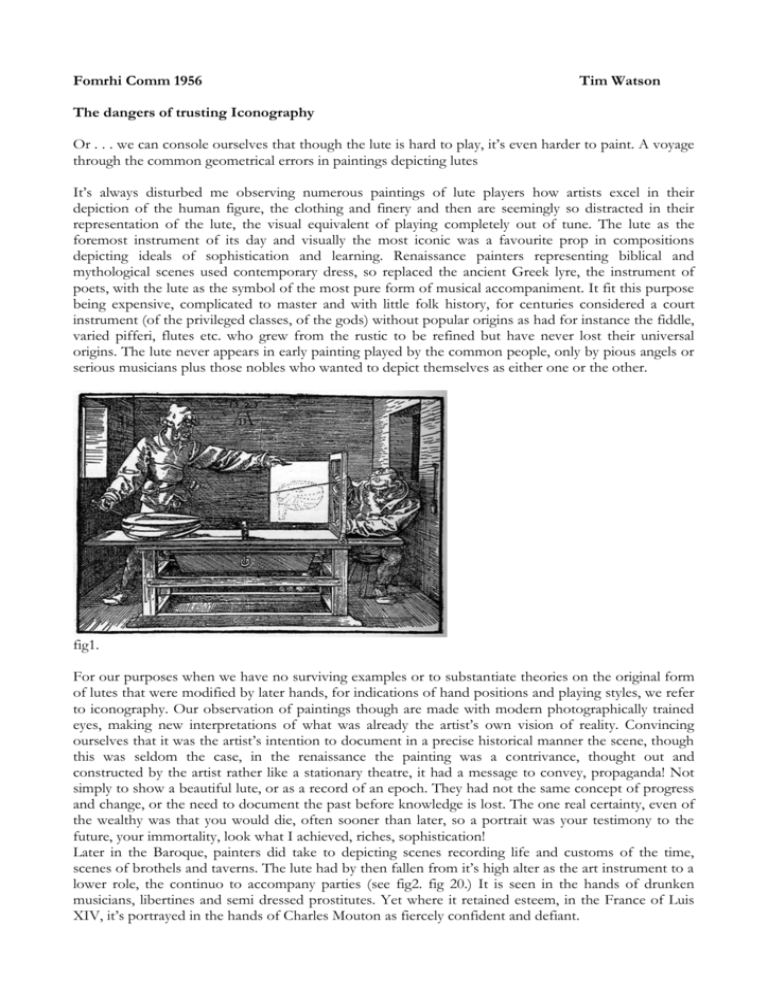

Fomrhi Comm 1956 Tim Watson The dangers of trusting Iconography Or . . . we can console ourselves that though the lute is hard to play, it’s even harder to paint. A voyage through the common geometrical errors in paintings depicting lutes It’s always disturbed me observing numerous paintings of lute players how artists excel in their depiction of the human figure, the clothing and finery and then are seemingly so distracted in their representation of the lute, the visual equivalent of playing completely out of tune. The lute as the foremost instrument of its day and visually the most iconic was a favourite prop in compositions depicting ideals of sophistication and learning. Renaissance painters representing biblical and mythological scenes used contemporary dress, so replaced the ancient Greek lyre, the instrument of poets, with the lute as the symbol of the most pure form of musical accompaniment. It fit this purpose being expensive, complicated to master and with little folk history, for centuries considered a court instrument (of the privileged classes, of the gods) without popular origins as had for instance the fiddle, varied pifferi, flutes etc. who grew from the rustic to be refined but have never lost their universal origins. The lute never appears in early painting played by the common people, only by pious angels or serious musicians plus those nobles who wanted to depict themselves as either one or the other. fig1. For our purposes when we have no surviving examples or to substantiate theories on the original form of lutes that were modified by later hands, for indications of hand positions and playing styles, we refer to iconography. Our observation of paintings though are made with modern photographically trained eyes, making new interpretations of what was already the artist’s own vision of reality. Convincing ourselves that it was the artist’s intention to document in a precise historical manner the scene, though this was seldom the case, in the renaissance the painting was a contrivance, thought out and constructed by the artist rather like a stationary theatre, it had a message to convey, propaganda! Not simply to show a beautiful lute, or as a record of an epoch. They had not the same concept of progress and change, or the need to document the past before knowledge is lost. The one real certainty, even of the wealthy was that you would die, often sooner than later, so a portrait was your testimony to the future, your immortality, look what I achieved, riches, sophistication! Later in the Baroque, painters did take to depicting scenes recording life and customs of the time, scenes of brothels and taverns. The lute had by then fallen from it’s high alter as the art instrument to a lower role, the continuo to accompany parties (see fig2. fig 20.) It is seen in the hands of drunken musicians, libertines and semi dressed prostitutes. Yet where it retained esteem, in the France of Luis XIV, it’s portrayed in the hands of Charles Mouton as fiercely confident and defiant. fig2. Fig3. Returning to the problem of the form of the lute. Plato theorised that every object has an idealised symbolic form, the way by which we recognise them. A chair may have many sizes, angles, decoration but the arrangement of its three basic elements, legs seat and back constrain us to recognise it as a chair. The lute too has its specific defining characteristics, the pear shape body, the rounded ribbed bowl, the short neck and the cranked peg box. When these elements are not represented correctly we no longer see it as a lute (see Gentileschi fig18.) though most art critics for simplicity seem to define any stringed instrument a lute ignoring the huge cultural difference of being portrayed with a lute or a lesser instrument, a very different message indeed. Geometrically the lute poses many problems to the artist. The only straight lines are the strings and it’s amazing how many artists failed on this one simple fact. The belly shape is a series of compound curves, as is the bowl with it ribs. The great difficulty comes however as the appreciation of these key elements requires multiple viewpoints, a clear view of the front face, in a normal playing position, prevents any sight of the bowl or the right angled peg box, provoking an early cubist approach where perspective and reality are contorted to represent the key elements all in one view. The resulting artist’s view of the lute thus becomes as a bag full of liquid, twisting and bulging in unlikely places. What if the artist took the same approach to the human figure! From the 1430’s artists such as Paolo Uccello developed a calculated method to represent reality through perspective, painting became superficially a snapshot depicting a single scene from a fixed point of view. The greatest artist/draughtsmen of the high renaissance made complicated construction drawings for their paintings with measured perspective and grids to cement objects in space with their correct proportions. We must however remember that many artists of the day were effectively artisans, initially apprenticed to a master and schooled in those arts necessary to survive making likenesses and little else. Those with talent to draw the human face succeeded, those with no talent mixed the colours for the master and filled in, I suspect they also painted the lutes in some of these pictures. Musicians or at least lutenists on the contrary received more education, could generally write, had studied harmony and thus some mathematics. Their time was spent at court, though in the role of a servant they had a broader idea of the world, artists though revered lived much more on the street. To survive, both must be good at their trade and would surely have concentrated all of their efforts on the attainment of excellence and invention, with little time to expand their knowledge in other fields. I am thus suspicious when an artist is claimed to have played the lute, Caravaggio, Gentileschi for example, when would they have found the time to study for the years it takes to reach a satisfactory aptitude, who would have given them lessons, and how would they pay for them? For the purpose of this study I have assessed paintings from the late renaissance to the high baroque, principally from the point of view of the geometry of the lute. In each case I constructed with the aid of 3D computer models a typical lute of the period. Superimposing over the original painting the appropriate perspective grid I have been able to recreate the viewpoint of the painted lute with the 3D model giving the comparison of a virtual photograph. Though quicker with modern technology, it is essentially the same process which Albreicht Durer outlines in his treatise ‘On mensuration with the compass and ruler in lines planes and whole bodies’ (1525) (see fig1.). fig 4. Fig5. Fig6. Bartolomeo Veneto (active 1502-1546) Worked in Venice Padova and Milan and much influenced by Leonardo da Vinci Lady playing a lute c.1520: versions; Academia Brera Milano, J.Paul Getty Museum Los Angeles www.getty.edu Several versions of this picture exist, some attributed to Bartolomeo, others probably copies, it was obviously a desirable subject to adorn your wall in the 1530’s. None of these seem to question the rather strange form of the lute represented which if analysed (see fig5.) presents the classic desire to show many views in one. The proportions of the lute, body and neck shows a very short belly, possibly an old instrument from the previous century though the rose design, a form of Jordanian knot seems to preclude this. This is also contradicted by Henri Arnault Zwolle’s treatise of 1450 which sought to define the rule of proportion for lutes, string length, neck/body length, position of the bridge and sound hole on the body, suggesting that there was already a certain standardisation even in the mid 15thC. The belly is infuriatingly asymmetrical, the lower side stretched downwards to meet the tabletop (he probably painted the figure and table first then compromised the lute to avoid re-working). The topside of the bowl, the first rib, is highlighted by a strong reflection, however as the computer model shows (fig5.) this would be impossible unless the face of the instrument was rotated to face towards the table top. Very little attention has been made to the correct alignment of the three principal parallel lines, the bridge, the neck/body joint and the nut. If we are to believe Bartolomeo’s geometry the neck would be twisted and the instrument completely unplayable. This seems to have more to do with creating the classic high renaissance triangular composition than geometrical accuracy, the peg box angle chosen to point towards the eyes of the figure. We see a bowl of a yellowish tint, probably maple or ash and the fingerboard of a reddish colour reminiscent of pear wood. What seems to be a thick rounded neck from the left hand position, is almost parallel along it’s length, the stings then splay from the neck joint to the bridge which is impossible as we know they must be straight lines. Note also that the player has a fur (faena) draped over her left arm. The theme of some heavy fabric drape over one arm re-occurs in several lute portraits (see Caravaggio fig13.) possibly a modern evocation of the classical Roman toga, not a feature that would aid freedom of movement. In frustration I have re-worked with the aid of the computer 3d model and Photoshop to place a more credible lute in the hands of our subject, she even seems happier as a result. (fig6.) fig7. fig.8 fig9. Hans Holbein the younger. (1497/98- 1543) Detail from The Ambassadors 1533. The National gallery London This painting which commemorates George de Selve ambassador to the Vatican and Venice and his friend Jean Dinteville, french ambassador to London. A simple rectilinear composition, more a statement of the culture of these two men than an artistic composition. Every element depicted is a statement to be read and interpreted, though for our restricted discussion we are interested only in the lute placed on a lower shelf of a cabinet. For those interested in the full reading of the painting I would refer to the excellent book: "Making and Meaning - Holbein's Ambassadors" by Susan Foister, Ashok Roy and Martin Wyld, published by National Gallery Publications (and distributed by Yale University Press) ISBN number: 1-85709-173-6 Also the interactive web site of the National Gallery http://nationalgallery.org.uk/ Hans Holbein was an exceptional draughtsman with an impressive attention not just in the human likeness, he drew what he saw avoiding stylised conventions, but also in his attention to the peripheral objects. His lute is presented with confidence in strong light from a difficult angle, the perspective is almost perfect. Quite probably he utilised a measured method for constructing the perspective as illustrated by Durer. So from this we should assume that the artist has taken pains to be as precise as possible. The basic form of the lute presents a very bulbous and deep body, making the comparison with a typical Laux Maler/Frei 6c rotated to the same perspective by the computer we can see that Holbein’s bowl is too vertical at the neck body joint and would be very deep, too deep for that position on the table. It does however illustrate well the heavily scalloped ribs. The profile of the soundboard must be also considerably rounder than the Bolognese style lutes that have survived from this period, the shape being much more similar to the idealised form described in the Arnault treatise, possibly again an older instrument from the late 15th century. From its relationship to the surrounding objects I estimate the lute to be a descant, 59cm diapason. If this were the case, by applying the perspective grid to the peg box it would mean the section at the neck body joint to be about 5.5cm deep with a V section and around 2,5cm at the nut with a more rounded profile. Thicker necks were common on early lutes but this would make the instrument impossible to play and must be an exaggeration. Stephen Barber and Sandy Harris have an extensive study on their web site www.lutesandguitars.co.uk, discussing in more detail the woods used, details of the pegs and potential stringing deducted from the thicknesses of the painted strings. The principal debate however must be whether this lute is drawn from an actual lute or is an invention from knowledge of the instrument and thus how much of the artists creativity entered into the equation, the peg heads for example would be both difficult to make and difficult to turn without using a turning key. fig10 fig11. fig12. Bartolomeo Passarotti (1529-1592) Man playing the lute 1576: Museum of fine arts Boston A very dynamic pose, the clothing is not overly fine and there are few other symbols to indicate riches or culture. This man wants to present himself as a musician! Strange then that the lute is painted with so little attention to detail, with obvious problems of symmetry and proportion (Fig10. The original with the lute evidenced). The bowl is shown on the top side and from the end, as the 3d model superimposed (fig11.) shows, this is geometrically impossible from this viewpoint, otherwise the nut as shown would be severely twisted relative to the neck body joint. The bowl seems extraordinarily deep, we would think that Passarotti being Bolognese, would have certainly painted a Maler or Frei shaped lute in stead of this bulbous body! The peg box is twisted at an impossible angle and the top row of pegs is strangely vertical, it all seems drawn by Picasso some 300 years later. There is also no sound hole visible. It’s interesting to note that this lute shows many similarities in shape and in the colours of the woods to the painting by Bartolomeo Veneto above, though painted some 50 years later it could be of the same model though well out of date by 1576. The whole depiction of the lute is so poor in relation to the player that it leads me to suspect that the subject was not actually holding anything when the painting was made and the instrument was added from memory, or copied from another painting, making our subject more someone wanting to seem to be a musician than the portrait of a famous lutenist. In the hope that this man really was a musician or at least an enthusiast I have re-elaborated the lute to give him a little musical dignity, at least in our eyes. (fig12.) fig13. Fig14. Michelangelo Merisi ‘il Caravaggio’ (1571-1610) Giovane che suona il liuto 1595: Metropolitan Museum of art New York See the interactive website http://www.caravaggio.rai.it/ where you can inspect the paintings in close detail without a costly plane ride to New York. The academics are in some doubt as to the authenticity of this painting, as it’s the second version of the same subject painted in a short time, though as we have seen with Bartolomeo Veneto, there was evidently a ready market for this subject. From my point of view, studying artists who have attempted to paint the lute, the correctness of the perspective and the attention to the detail of strings, their colour and thickness, the pegs, double tied frets was something beyond the capability of most artists of the period, particularly as this is obviously painted from life, with the model and lute in front of the artist, the details are too naturalistic to be constructed mathematically. This second version revisits the subject but is not a copy, the boy is the same but the lute is a different instrument as are many other details. fig15 detail It is possible that a disciple of Caravaggio painted it, I would suggest Bartolomeo Manfredi, but only because of the strange coincidence that painters with the name Bartolomeo (Veneto, Passarotti, Bartholomeus Van de Helst ) have all tackled the subject of lute players. Manfedi certainly painted several lute players but never with the precise geometry of this painting. Superimposing a typical Venetian style 7c of the late 16thC it is impressive how the form, neck and bowl correspond almost exactly. Only the rose is too far down the soundboard. From this it is easy to state that this was exactly the style of lute before the artists eyes, the painting does not have the finesse of the Holbein but that only shows that is was painted more quickly from a live model. fig16. Fig17. Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1652 Woman playing a lute 1610-12: Spada gallery Rome If painted by Atemisia, there is some discussion that it is by her father Orazio, as she was still less than twenty years old at the time and a woman! So the male critics find it all hard to believe. She was a close follower of Caravaggio in the technique of painting from live models and her paintings are both expressive and extremely realistic. In the picture the angelic Saint Cecilia is playing a lute and gazing towards heaven. The lute however displays many atypical features to make us suppose that it was not drawn entirely from life. First and most simply the instrument is suspended in the air with no restraining strap and the saints hands are restraining it with no apparent force, a miracle! The neck body joint is highly unusual as is the light and dark reflections on the soundboard, giving the impression of a highly deformed surface, dishing then bulging before flattening around the edge (see also ter Brugghen fig20). Analysing the perspective we find a body to neck ratio, which would give 11 frets on the neck. The string spacing is ambiguous, they are probably six double courses but are painted as twelve singly spaces. This would lead us to suppose that Gentileschi did not paint this from a model and had only a general knowledge at the time of the details of the lute, she was young and sexually abused so perhaps this was the least of her worries. fig18. Fig19. Self portrait as a lute player 1615-17: Curtis Galleries Minneapolis http://www.metmuseum.org Three to five years later Gentileschi painted this self-portrait depicting herself as a lutenist! Again the lute demonstrates certain peculiarities, the overlay of a computer model shows that the instrument painted has an oval form and a flat back, guitar like construction. This further substantiated by a very untypical rose design and decorated/curled points at the neck joint. Again it must be an extremely light instrument as nether hand is able to support it’s weight and her right hand would have the utmost difficulty in making anything but the most rudimentary strum. Did she really know how to play as the art critics suggest? fig20 Hendrick ter Brugghen (1588-1629) A man playing a lute 1624: The National gallery London http://nationalgallery.org.uk/ fig21 This lutenist has a decidedly red nose, from an excess of wine and perhaps the artist was drinking from the same jug when he painted the lute! Again the now obligatory asymmetry of the belly, the lower half being much larger. The lute would seem to have enough pegs for eleven courses but only ten courses of strings. The debate though of this lute is the play of light on the soundboard, giving the impression of an arched top, violin style, as seen previously in the painting by Gentileschi. We have no evidence of this in existing lutes from the period, is it the true depiction of a very thin and heavily deformed soundboard or artistic licence to make a flat form more interesting? The accurate tapering of the shadows does suggest the former. fig22 fig23 Fig24 Jean de Reyn, French (1610-1678) The lute Player 1640: Boston Museum of fine arts http://www.mfa.org A flash confident figure, dressed for success, note the speedy Futurist boots, however the reconstruction of the painted lute shows he should perhaps have a serious talk to his lute maker, or more probably the artist. The shape of the lute is twisted and asymmetrical, the painter has become particularly confused at the neck body joint. The seemingly oversized peg box in reality is in proportion, just much less tapered than we would think typical. The geometry suggests the neck joint being so bent so that the stings would pass centimetres from the frets making it a bit of a dog to play. Taking one side of the body as true, results in a Venetian style lute, though we know the French preferred the early Frei/Maler bodies. The ribs of the bowl are lost in the darkness of the clothing which is a pity as this point of view does finally show the key characteristics all in one view. Conclusion To take any artist’s rendition of a lute as a strictly accurate basis for a reconstruction would result in twisted deformed and more to the point lutes that were impossible to play. If however we are to interpret the intention of the artist correcting or discarding details or shapes that we think are inaccurate then we risk applying preconceptions with little sustainable proof. If for example a belly is asymmetrical, which side do we take as true, this can mean the difference between Frei or a Dieffopruchar body, which results in a very different lute As to the artists, I think we could have pretended at little more attention and accuracy, after all critical observation was their trade. If they had drawn the face of their patron so badly deformed they would certainly not have been paid. From this criticism I would except Carravaggio, who rather than being the quick tempered hothead who we read about, for me was surely a dedicated hard worker, fastidiously precise in his observation of form and detail. Note above in the detail of the peg box, there are two rogue heart shaped pegs, replacements for broken ones? Only an artist slavishly dedicated to observing reality would resist the temptation to simply correct this detail and paint them all alike for spiritual harmony. It’s just a pity he painted lutes that we already know quite a lot about and apart from their obvious beauty give us no great revelation or secrets. Tim Watson 2011