Models of Memory

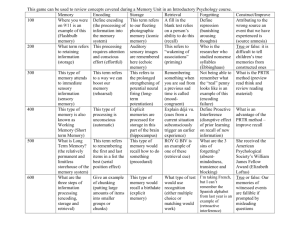

advertisement

MEMORY Introduction to Memory What is memory? What is the difference between learning and memory? There are three stages: 1. encoding 2. storage 3. retrieval Short-Term Memory (stm) 1. 2. very limited capacity very limited duration acoustic encoding method there are two main ways of researching the capacity of stm span measures free recall Span Measures Miller (1956) – 7+/- 2 items can be stored in stm Miller said the key issue is chunking Recency Effect People remember things better if they happened recently The recency effect in stm can be measured using free recall Participants are shown a list of words/syllables and asked to recall them in any order immediately after the list was presented The last few items on the list are usually better remembered than itmes in the middle of the list Glanzer and Cunitz (1966) found that counting backwards for only 10 seconds between the end of the list presenteation and the start of recall virtually eliminated the recency effect In other words, people remember a similar number of words from earlier in the list, but not the few at the end Could this be because the two or three words at the end of the list were not encoded aswel, thus being wiped our by counting backwards? This counting backwards is called an interference task What is the primacy effect? The recency effect suggest the cacpcity of stm is two or three items, but span measures suggest about 7 items?? Why? Different patterns of rehearsal: o Span task – subjects rehearse as many items as possible 1 o Free recall – subjects learn a list of only a few items at a time Duration of stm Peterson and Peterson (1959) – people could recall trigrams (3 unrelated consonants) after 3 seconds, they recalled fewer trigrams after 6 seconds and after 18 seconds recall was very poor Conclusion – memory trace in stm has just about disappeared after 18/20 seconds Long-Term Memory (ltm) Unlimited capacity Semantic encoding method mainly Difficult to assess how long a memory lasts Episodic and Semantic Memory Two types of ltm Episodic – autobiographical flavour Episodic – contains information of specific events Episodic – e.g. what you did yesterday Semantic – knowledge of the world Semantic – e.g. capital of grance and how to fill your car with petrol Explicit and Implicit Memory The memory tests discussed so far (free recall etc) all involve the use of direct instructions of participants to retrieve specific information Such memory tests are of explicit memory (conscious recollection/awareness) Implicit – performance on a task is facilitated with the absence of conscious recollection (unconscious recollection/awareness) Declarative and Procedural Knowledge Systems Cohen and Squire (1980 – ltm is divided into two memory systems (declarative and procedural) i.e. knowing that and knowing how declarative – nowing that procedural – knowing how Models of Memory Multi-Store Model This model of memory suggests that memory consists of several (i.e. multi) stores. The most influential multistore model was proposed by Atkinson and Shiffrin (1968). According to their model, memory is made up of three separate stores – sensory store, STS and LTS. 2 The sensory store transfers data to STM. It is made of five stores, one for each sense (sight, hearing, touch, taste, smell). However, much research has focused on the visual or iconic store and the auditory or echoic store. The iconic store is a sensory memory store for visual data and the echoic store is a sensory memory store for auditory data. This multistore model sees STM as a crucial part of memory, as it suggests that without it data cannot get into or out of LTM. According to this model also, rehearsal plays a very important role. The longer information is held in STM the more likely it is to be transferred to LTM, according to this model. Levels of Processing Model Basically this model suggests that the way information is encoded affects how well it is remembered. The deeper the level of processing, the easier the information is to recall. It was proposed by Craik and Lockhart (1972) and is an alternative to the multistore model (because remember the remaining model of memory – Working Memory Model is a model of short-term memory only). Craik and Lockhart did NOT reject the idea of memory stores, as they accepted the existence of a short term and long term memory store. BUT, rather than focusing on stores and how information is transferred from one store to another, this Levels of Processing Model focuses on how information is ENCODED and PROCESSED. According to this model of memory, information can be encoded and processed at different levels. It argues that the level at which data is processed accounts for the likelihood of it being learned and remembered. The model identifies various levels of processing from the shallowest to the deepest. Here are some examples: At the shallowest level, words are presented visually (in terms of their physical appearance). E.g. is the following word in capital letters or lower case letters? ‘FISH’ At a deeper level still, words are processed acoustically (in terms of their sound). E.g. does the following word rhyme with ‘pin’ STYLE? At the deepest level, words are processed semantically (in terms of their meaning). E.g. is a PANCAKE a form of transport? To answer this, you need to focus on the meaning of the words (i.e. the semantics of the words). Craik and Lockhart argue that the deeper the level of processing, the stronger and more durable and long lasting the memory. Working Memory Model This model is a model of short term memory only and was put forward by Baddley and Hitch (1974). They criticise the multi store model for being too simplistic in terms of short term memory and suggest that short term memory is made up of various sub-components. 3 This model suggests short term memory is not a unitary system (i.e. a single system); short term memory according to Baddley and Hitch has three sub-systems – each having specialised skills for particular tasks. This model goes on to suggest that information is not just rehearsed in STM, but is instead analysed, evaluated and worked on. Central Executive is one component or sub-system. It supervises and coordinates the other slave systems (i.e. the phonological loop and the visuo-spatial sketch pad). It decides which system is required and coordinates the retrieval of information from LTM. E.g. use the example I gave you about working out how many windows you have in your house. The central executive decides what working memory pays attention to. E.g. two activities sometimes come into conflict such as driving a car and talking. Rather than hitting a cyclist who is wobbling all over the road, it is preferable to stop talking and concentrate on driving. The central executive directs attention and gives priority to particular activities. Phonological Loop or articulatory loop, consist of two parts: 1. The phonological Store – holds spoken words for 2 seconds approximately. Spoken words enter the store directly. Written words must first be converted into an articulatory code (spoken code) before they can enter the phonological store. 2. The Articulatory Control Process acts like an inner voice rehearsing data from the phonological store. It circulates information round and round like a loop. This is how we remember a telephone number etc. As long as we keep rehearsing it, we can retain the information in working memory (i.e. short term memory). Visuo-Spatial Sketch Pad deals with visual and spatial information. Visual data refers to what things look like and spatial data refers to the layout of items relative to each other. The sketchpad does not simply store visual and spatial data, it also analyses and manipulates it. It is as if we take time to move our eyes along an image in memory (i.e. the example of counting the number of windows in your house. You have to obtain a picture of your house from LTM and then hold it in the visuo-spatial sketch pad to see/visualise all the windows in order for you to count them). Forgetting STM Forgetting in stm is likely to be due to a failure of availability because it has a limited capacity store Trace Decay In a study by Peterson and Peterson it was found that recall dropped from 80% after 3 seconds recall to under 20% when the retention interval was 18 seconds But what caused this drop in recall? One possibility is that the memory trace simply disappears if not rehearsed This is call the Trace Decay Theory This theory is based on the idea that memories have a physical basis (trace) and that this will decay in time unless the trace is passed to ltm 4 Information in stm certainly does disappear but it may not be because of decay – it may be because of interference Displacement Material currently circulating in stm which has not been process enough to pass to ltm, will be pushed out or displaced by new incoming information This explanation is very simple and logical because stm is said to have a very limited capacity (7 items approximately) and so when stm is full, new information pushed out or displaced old information Interference Another possibility for the Peterson and Peterson findings is that the interference tasks caused retroactive interference This occurs when a second set of information (i.e. counting backwards) interferes with learning original (older information) It is most likely to happen when the two sets of information are similar LTM Trace Decay Theory Forgetting might also be due to the physical decay of memory trace in ltm, as in stm It has proved hard to study these physical changes directly As a result, test of trace decay theory have been somewhat indirect It is assumed that if a person does nothing during the time of initial learning and subsequent recall, and they forget the material, then the only explanation can be that the trace has disappeared Jenkins (1924) asked two students to recall nonsense syllables at intervals between one and eight hours The students were either awake or asleep during the retention interval There was much less forgetting when the students were asleep that when awake If the trace decay theory is correct, then we would expect the same amount of forgetting whether they were asleep or awake The fact that this was not true, suggests that the interference from other activities was responsible for the increase in forgetting, rather than decay? Interference When previous learning interferes with new learning (proactive interference) An experiment by Mc Donald (1931) highlighted proactive interference Participants learned a set of adjectives until they could recall them perfectly Some of the participants then spent 10 minutes resting, while other learned new material The more similar the new material to the original, the more the recall of the original list declined Participants who spent 10 minutes resting without any new material to learn had the highest recall 5 This suggests that retroactive interference affected recall and indicates that the more similar the later material, the greater the interference Retrieval Failure If data is stored in ltm then it is available, but sometimes it may not be accessible This is known as retrieval failure Retrieval failure may be due to poor or insufficient retrieval cues Retrieval cues may be based on context (setting or situation in which information is encoded and retrieved) – context dependent retrieval Retrieval cues may be based on state (physiological or physical) of person when data is encoded and retrieved – state dependent retreival Emotional Factors and Forgetting Emotion plays an influential role in forgetting When we talk of emotion and forgetting, we are focusing our attention on two types of emotionally charged memories 1. flashbulb memories (long lasting, vivid memories, e.g. death of Diana) 2. repressed memories (Freud says we push some memories into our unconscious because to recall such memories may provoke anxiety, e.g. child sexual abuse) Repression is motivated forgetting without conscious awareness 6 Eyewitness Testimony Reconstructive Memory - Bartlett (1932) Bartlett’s theory of Reconstructive Memory is crucial to an understanding of the reliability of eye witness testimony (EWT) as he suggested that recall is subject to personal interpretation dependent on our learnt or cultural norms and values- the way we make sense of our world. In other words, we tend to see and in particular interpret and recall what we see according to what we expect and assume is ‘normal’ in a given situation. Bartlett referred to these complete mental pictures of how things are expected to be as Schemas. These schemas may, in part, be determined by social values and therefore prejudice. Schemas are therefore capable of distorting unfamiliar or unconsciously ‘unacceptable’ information in order to ‘fit in’ with our existing knowledge or schemas. This can, therefore, result in unreliable eyewitness testimony. Bartlett tested this theory using a variety of stories to illustrate that memory is an active process and subject to individual interpretation or construction. Have a go! Read the following story and then remove from screen and attempt to recall it. The War of the Ghosts. One night two young men from Egulac went down to the river to hunt seals, and while they were it became foggy and calm. Then they heard war cries and they thought; ‘Maybe this is a war-party.’ They escaped to the shore, and hid behind a log. Now canoes came up, and they heard the noise of paddles and saw one canoe coming up to them. There were five men in the canoe and they said; ‘What do you think? We wish to take you along. We are going up the river to make war on the people.’ One of the young men said; ‘I have no arrows.’ ‘Arrows are in the canoe,’ they said. ‘I will not go along. I might be killed. My relatives do not know where I have gone. But you, ’he said turning to the other, ’May go with them.’ So one of the young men went, but the other returned home. And the warriors went on up the river to a town on the other side of Kalama. The people came down to the water and began to fight, and many were killed. But presently, one of the young men heard one of the warriors say; ’Quick let us go home. That Indian has been hit.’ Now he thought; ‘Oh, they are ghosts.’ He did not feel sick, but he had been shot. So the canoes went back to Egulac, and the young man went back to his house and made a fire. And he told everybody and said; ‘Behold, I accompanied the ghosts, and we went to fight. Many of our fellows were killed and many of those that attacked us were killed. They said I was hit, but I did not feel sick.’ He told it all, and then he became quiet. When the sun rose, he fell down. Something black came out of his mouth. His face became contorted. The people jumped up and cried. He was dead. 7 According to Bartlett your recall will show a westernised interpretation of this American Indian folk tale thus illustrating your subjective memory construction rather than accurate objective recall of events. How might this idea be applied to eyewitness testimony of criminal occurrences. Reconstructive Memory - Loftus (1974) Loftus drew on the ideas of Bartlett and conducted research illustrating factors which lead to inaccurate recall of eye-witness testimony. Loftus & Palmer (1974) conducted two laboratory experiments to illustrate this reconstrutive memory and how this is influenced by questioning techniques used by the police. Experiment One. 45 participants involved using an independent measures design. Participants were shown films of traffic accidents. They were then given a general account of what they had just seen and asked a series of questions about it. The critical question asked was ‘About how fast were the cars going when they HIT each other?’ OR the word ‘HIT’was replaced by either ‘SMASHED’, ‘COLLIDED’, ‘BUMPED’ or ‘CONTACTED’. The results suggested that participants recall was influenced by the word used - the independent variable. The word ‘smashed’ led to the fastest speed estimate and the word ‘contacted’ the slowest Experiment two The experiment above could be explained by response bias - pressure from interrogator or a change in participants recall of the event because of word used in question. Loftus & Palmer conducted this experiment in order to test which explanation was accurate. 150 students were tested using independent measures design. They were then given a general account of what they had seen. They were then divided into groups of 50. The first group was asked ‘How fast were the cars going when they hit each other?’ The second group were asked ‘How fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?’ The third group were not asked the question at all and acted as a control group. One week later they were asked a series of questions about the road traffic accident, one of which was the critical question, ‘Did you see any broken glass? Yes or No?’ There was no broken glass in the film itself. The results suggested that the word ‘SMASHED’ not only led to estimates of faster speeds but also increased the likelihood of the participants recalling seeing broken glass when none was in the film. This research suggests that memory is easily distorted by questioning technique and information acquired after the event can merge with original memory causing inaccurate recall or reconstructive memory. The addition of false details to a memory of an event is referred to as conflabulation. The Loftus & Palmer experiment can be criticised for lacking ecological validity. It employed independent measures design and therefore may be explained by individual differences/subject variables. The controlled 8 conditions make for sound reliability the ethics of this design may be questioned, as the participants were deceived but this was necessary in order to validate findings and minimise demand characteristics. The participants may have been distressed/traumatised by the film and this emotional reaction may have influenced their interpretation of the event. See Research Methods. This kind of research has led to recommendations concerning police interview techniques and can be used by lawyers in court to question the accuracy of EWT. Face Recognition The work of Loftus & Palmer can be applied to face recognition. This area of EWT has however been studied directly to order to avoid false accusations. Cohen (1966) showed how faces are not seen in isolation but that they are perceived or influenced both by the event itself and by people’s schema, social norms and values and therefore stereotyped images. Cohen referred to this as Cross-Race Identification Bias. Cohen suggested that people find it easier to identify people from their own race than people from a different race. This is reflected in the statement, ‘They all look the same!’ Therefore when an eyewitness and a possible suspect are from different races the identification of the suspect must be treated with caution. Cohen illustrated this by asking 86 shop workers in Texas to identify three customers, one White, one African-American and one Mexican-American who had purchased something from the shop that day. One third of the customers were White, one third African-American and one third Mexican-American. The accuracy of their recall was different for customers of different races and was related to the race of the shop worker. This research may have involved demand characteristics and individual differences. Cohen points out that it is difficult to recognise people out of the context in which you would ordinarily have contact with them, ‘It is hard to recognise your bank manager at the disco or your dentist at in evening dress’, (Cohen 1996). Therefore the difference between the actual scene of the crime and an identity parade may be misleading as memory is often cue- or context-dependent. Young showed how we are more likely to wrongly identify someone the less we know them. Young asked 22 participants to record how many times they made errors in recognising people over an eight week period. There were 314 cases of mistaking a stranger for someone they knew because of similarity or dress or build. This research has implications for face recognition in identity parades. Dood & Kirschenbaum (1973) illustrate the problem of facial recognition by their Case Study of Ron Shatford. The witness had described the suspect as ‘attractive’. Shatford was placed in an identity parade in which in which he was the only ‘attractive’ member. He was wrongly selected. Case studies are unrepresentative, making generalisations impossible. Well (1993) showed how the witness assumes the suspect to be present in an identity parade which again may lead to false recognition. Lindsay (1991) suggested that suspects in an identity parade should be viewed one at a time rather in a line-up in order to avoid functional size (fair number of feasible suspects to chose from) and reduce possibility of mistaken identity. Bull & Rumsey proposed that we judge people to be criminal on their appearance. 9 Reconstructive Memory - Loftus (1974) Loftus drew on the ideas of Bartlett and conducted research illustrating factors which lead to inaccurate recall of eye-witness testimony. Loftus & Palmer (1974) conducted two laboratory experiments to illustrate this reconstrutive memory and how this is influenced by questioning techniques used by the police. Experiment One. 45 participants involved using an independent measures design. Participants were shown films of traffic accidents. They were then given a general account of what they had just seen and asked a series of questions about it. The critical question asked was ‘About how fast were the cars going when they HIT each other?’ OR the word ‘HIT’was replaced by either ‘SMASHED’, ‘COLLIDED’, ‘BUMPED’ or ‘CONTACTED’. The results suggested that participants recall was influenced by the word used - the independent variable. The word ‘smashed’ led to the fastest speed estimate and the word ‘contacted’ the slowest. Experiment two The experiment above could be explained by response bias - pressure from interrogator or a change in participants recall of the event because of word used in question. Loftus & Palmer conducted this experiment in order to test which explanation was accurate. 150 students were tested using independent measures design. They were then given a general account of what they had seen. They were then divided into groups of 50. The first group was asked ‘How fast were the cars going when they hit each other?’ The second group were asked ‘How fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?’ The third group were not asked the question at all and acted as a control group. One week later they were asked a series of questions about the road traffic accident, one of which was the critical question, ‘Did you see any broken glass? Yes or No?’ There was no broken glass in the film itself. The results suggested that the word ‘SMASHED’ not only led to estimates of faster speeds but also increased the likelihood of the participants recalling seeing broken glass when none was in the film. This research suggests that memory is easily distorted by questioning technique and information acquired after the event can merge with original memory causing inaccurate recall or reconstructive memory. The addition of false details to a memory of an event is referred to as conflabulation. 10 The Loftus & Palmer experiment can be criticised for lacking ecological validity. It employed independent measures design and therefore may be explained by individual differences/subject variables. The controlled conditions make for sound reliability the ethics of this design may be questioned, as the participants were deceived but this was necessary in order to validate findings and minimise demand characteristics. The participants may have been distressed/traumatised by the film and this emotional reaction may have influenced their interpretation of the event. See Research Methods. This kind of research has led to recommendations concerning police interview techniques and can be used by lawyers in court to question the accuracy of EWT. Face Recognition The work of Loftus & Palmer can be applied to face recognition. This area of EWT has however been studied directly to order to avoid false accusations. Cohen (1966) showed how faces are not seen in isolation but that they are perceived or influenced both by the event itself and by people’s schema, social norms and values and therefore stereotyped images. Cohen referred to this as Cross-Race Identification Bias. Cohen suggested that people find it easier to identify people from their own race than people from a different race. This is reflected in the statement, ‘They all look the same!’ Therefore when an eyewitness and a possible suspect are from different races the identification of the suspect must be treated with caution. Cohen illustrated this by asking 86 shop workers in Texas to identify three customers, one White, one African-American and one Mexican-American who had purchased something from the shop that day. One third of the customers were White, one third African-American and one third Mexican-American. The accuracy of their recall was different for customers of different races and was related to the race of the shop worker. This research may have involved demand characteristics and individual differences. Cohen points out that it is difficult to recognise people out of the context in which you would ordinarily have contact with them, ‘It is hard to recognise your bank manager at the disco or your dentist at in evening dress’, (Cohen 1996). Therefore the difference between the actual scene of the crime and an identity parade may be misleading as memory is often cue- or context-dependent. Young showed how we are more likely to wrongly identify someone the less we know them. Young asked 22 participants to record how many times they made errors in recognising people over an eight week period. There were 314 cases of mistaking a stranger for someone they knew because of similarity or dress or build. This research has implications for face recognition in identity parades. Dood & Kirschenbaum (1973) illustrate the problem of facial recognition by their Case Study of Ron Shatford. The witness had described the suspect as ‘attractive’. Shatford was placed in an identity parade in which in which he was the only ‘attractive’ member. He was wrongly selected. Case studies are unrepresentative, making generalisations impossible. Well (1993) showed how the witness assumes the suspect to be present in an identity parade which again may lead to false recognition. Lindsay (1991) suggested that suspects in an identity parade should be viewed one at a time rather in a line-up in order to avoid functional size (fair number of feasible suspects to chose from) and reduce possibility of mistaken identity. Bull & Rumsey proposed that we judge people to be criminal on their appearance. 11 Memory Worksheet 1: Introduction 1. What happens to information taken in by our senses? 1st information is: 2nd this information is: 3rd information can then be: 2. Define the following terms: Encoding: Storage: Retrieval: 3. William James said there are two different memory stores. What are they? 4. What are the different ways of encoding information? ---- -------encoding ----- ----encoding ---- -----encoding 5. Which principal method of encoding does short term memory use? 6. Which principal method of encoding does long term memory use? 7. Evidence suggesting that we use acoustic coding comes from research by Conrad (1964). Briefly describe the procedures involved in this research involved. 12 8. What are the findings of this study by Conrad (1964). 9. What conclusion can be drawn from these findings? 10. Who carried out a similar study two years later? 11. What was the aim of this study (1966)? 12. What are the procedures of this study? 13. Summarise the findings of this study. 14. What can be concluded from this study? 15. What is the capacity of short term memory? 16. What does the term ‘chunking’ mean? 13 17. What is the duration of short term memory? 18. What is the capacity of long term memory? 19. What is the duration of long term memory? 20. In short term memory information is stored and retrieved ‘sequentially’. What does this mean? 21. In long term memory information is stored by ‘association’. What does this mean? 22. Briefly outline the procedures, findings and conclusions of the study by Bower (1969) which looked at recall and organisation of memory. 23. Retrieval of information can be improved by context. Baddley (1975) asked deep sea divers to…… 24. What are the findings of this study of deep sea divers? 14 25. What can one conclude from these findings of Baddley (1975)? 15 Memory Worksheet 2: Models of Memory 1. There are three models of memory. What are they? 2. Who proposed the Multi Store model? 3. Who proposed the Levels of Processing model? 4. Who proposed the Constructivist approach? 5. Outline the Multistore model of memory. 6. State one criticism of the multistore model of memory. 7. Outline the Levels of Processing model of memory. 16 8. State one criticism of the Levels of Processing model. 9. Outline the Constructivist approach to memory. 10. State one criticism of the Constructivist approach to memory. 17 Memory Worksheet 3: Forgetting 1. What does the ‘Interference theory’ of forgetting? 2. Define the following terms: Retroactive Interference: Proactive Interference: 3. Postman et al (1960) researched Retroactive interference. Outline the procedures, findings and conclusion(s) of this study; 4. How was Retroactive interference demonstrated? 5. Give one criticism of the Interference theory: 6. What is ‘motivated forgetting’? 7. Loftus and Burns (1982) highlighted an alterative theory as to why we sometimes fail to remember unpleasant experiences. Summarise this study: 18 8. What is amnesia? 9. What are the two types of amnesia? 10. Define the following terms: Anterograde amnesia: Retrograde amnesia: 11. What is the Trace Decay Theory? 12. Jenkins et al (1924) carried out a study to see if forgetting is due to the passage of time or interference. Describe this study briefly: 13. What is the everyday application of the study by Jenkins et al? 19 Memory Worksheet 4: Eyewitness Testimony 1. Who is Elizabeth Loftus? 2. Loftus and Palmer (1974) showed participants several films of car accidents. Briefly describe this study and summarise the results found. 3. What five factors affect the reliability of memory? 4. What are ‘leading questions’? 5. How does ‘emotion’ affect memory? 6. How does ‘context of questionning’ affect memory and what is the ‘Cognitive Interview’? . 20 7. How does ‘physiological arousal’ affect memory? 8. How does ‘face recognition’ affect memory? 9. Valentine and Bruce (1988) looked at our ability to recognise faces when they are moving and showing emotion. Highlight this study. 21