Michał Moch

advertisement

Michał Moch

Graduate School For Social Studies

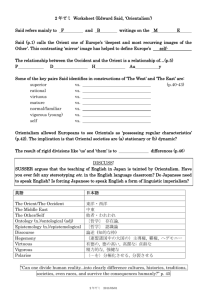

Concepts of orientalism and occidentalism in contemporary social

sciences – new meanings of traditional terms

Today we observe intriguing changes in the sphere of mass consciousness. Old terms

and notions acquire new meanings that differ a lot from former understandings. Building of

the world through usage of terms that were created for purposes of Western civilization – this

intellectual process is researched and criticized in works of many luminous scholars. It is also

the case of such words and important notions as ‘orientalism’ and opposite to latter

‘occidentalism’. Contemporary discussion concerning the very term of ‘orientalism’ has

begun with the publication of the crucial dissertation Orientalism by Edward R. Said (1978),

American with Palestinian background, theorist of literature and famous essayist. In my essay

I’m going to recapitulate briefly the discussion caused by mentioned text and to think how it

influenced on contemporary social sciences. A very important and basic thing is to define old

and new, traditional and modern, meanings of ‘orientalism’ and ‘occidentalism’.

1. Short history of ‘orientalism’

I could begin my discussion of the terms with the simple encyclopaedic definition of

‘orientalism’. It is the study of Near and Far Eastern societies and cultures, languages and

peoples by Western scholars. It can also refer to the imitation or aspects of Eastern cultures in

the West by writers, designers and artists1. Like the term Orient itself Orientalism derives

from a Latin word Oriens referring simply to the rising of the sun, to imply ‘the East’ in a

relative sense. This is the opposite of the term Occident, which has largely dropped from

common usage in its traditional sense. We could also mention similar terms: French-derived

Levant and Anatolia, from the Greek anatole, two further locutions for the direction in which

the sun rises2. In terms of the Old World, Europe was considered to be ‘The West’ or

‘Occidental’ and the furthest known Eastern extremity was called ‘the East’ or ‘the Orient’.

Since at least the Roman Empire until at least the Middle Ages; what is now considered to be

‘the Middle East’ was then considered ‘the Orient’. During that period, the flourishing

cultures of the Far East (on territories of modern China, Vietnam and so on) were unknown in

1

Compare: entry Orientalism in: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia [Internet:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orientalism, May 2006].

2

Ibidem.

2

Europe, just as the Old Continent was essentially unknown in the Far East. For example, the

Chinese name for China translates to ‘The Middle Kingdom’.

The encyclopaedic definition of understanding and contexts of ‘the Orient’ is worthy

of citing:

“Over the time, the common understanding of ‘the Orient’ has continually shifted East

as Western explorers travelled deeper into Asia. In Biblical times, the Three Wise Men

'from The Orient' were actually Magi from "The East" (relative to Palestine), now

understood to be from 'The Persian Empire' also known by the Greeks as Media. Since

then, as Europe gained expanding knowledge of the seemingly endless "Eastern

Frontier", the definition of 'The Orient' progressively shifted Eastwards, until the

Pacific Ocean was reached, in what is now also known as 'The Far East'. This can

cause some confusion about the historical and geographic scope of Oriental studies.

However, there still remain some contexts where 'The Orient' or 'Oriental' refer

to older definitions. For example, 'Oriental Spices' typically come from regions

extending from the Middle East through the Indian sub-continent to Indo-China3. Also,

travel on the Orient Express (from Paris to Istanbul), is East bound (towards the sun

rise); but does not reach what is currently understood to be The Orient. In France, the

terms "Orient" and "Orientals" can also still be understood to refer primarily to the

Middle East and North Africa. In contemporary English, Oriental is usually a

synonym for the culture and goods from the parts of East Asia traditionally occupied

by East Asians and Southeast Asians, excluding Indians, Arabians and other more

westerly peoples.

It is difficult to be precise about the origin of the distinction between the

"West" and the "East". However the rise of both Christianity and Islam produced a

sharp opposition between European Christendom and the Muslim cultures to the East

and in North Africa. During the Middle Ages Islamic peoples were demonised as

"alien" enemies of the Christian world. European knowledge of cultures further to the

East was very sketchy indeed. Nevertheless, there was a vague awareness that

complex civilizations existed in India and China, from which luxury goods such as

3

Ibidem.

3

woven textiles and ceramics were imported. As European explorations and

colonisations expanded a distinction emerged between non-literate peoples, for

example in Africa and the Americas, and the literate cultures of the East”4

In the 18th century Enlightenment thinkers sometimes characterized aspects of Eastern

cultures as superior to the Christian West. For example Voltaire promoted research into

Zoroastrianism in the belief that it would support a rational Deism superior to Christianity.

Others praised the religious tolerance of Islamic countries in contrast with the Christian West,

or the status of scholarship in Mandarin China. With the translation of the Avesta by Abraham

Anquetil-Duperron and the discovery of the Indo-European languages by William Jones

complex connections between the early history of Eastern and Western cultures emerged.

However, these developments occurred in the context of rivalry between France and Britain

for control of India, and were associated with attempts to understand colonised cultures in

order more effectively to control them. Liberal economists such as James Mill dismissed

Eastern countries on the grounds that their civilizations were static and corrupt. Even Karl

Marx characterised the “Asiatic mode of production” as unchanging.. Some aspects of Islamic

tradition as synonym of backwardness and statism were sharply criticized by Ernest Renan.

Despite this, the first serious European studies of Buddhism and Hinduism were

undertaken by scholars such as Eugene Burnouf and Max Müller. Serious study of Islam also

emerged through Edward William Lane and other scholars. By the mid-19th century "Oriental

studies" was becoming an established academic discipline, represented in respected European

universities such as Tubingen, Leiden and so on . However, while scholarly study expanded,

so did racist attitudes and popular stereotypes of “wily” orientals. Often scholarly ideas were

mixed with such prejudicial racial or religious assumptions. Eastern art and literature were

still seen as "exotic" and as inferior to Classical Graeco-Roman ideals. Their political and

economic systems were generally thought to be feudal “oriental despotisms” (comaparable to

ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia) and their alleged cultural inertia was considered to be

resistant to progress. Many critical theorists regard this form of Orientalism as part of a larger,

ideological colonialism justified by the concept of the “white man's burden”. Edward Said’s

critic was rooted in this negative conception of Orientalism.

Ibidem. Polish definitions of ‘orientalism’, contained in main dictionaries, don’t mention Said’s pejorative

reformulation of the term.

4

4

Oriental elements can be easily found in Medieval, Renaissaince and Baroque art, but

in the 19th century became an established and very important element. Myth of the Orient as

exotic, corrupted, feudal and also full of erotic sensuality was articulated in works of such big

artists as Eugene Delacroix, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres and Henri Matisse5. Some

artists viewed Orient as a mirror for ‘the West’ and the Western culture itself eg Gustave

Flaubert’s novel Sallambo with the methaphorical portrait of Carthage in Northern Africa.

Romantic literature (eg. Johan Goethe, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Samuel Taylor Coleridge,

Adam Mickiewicz) treated oriental motives as an important source of inspiration, but still it

was the vision of oriental (especially Islamic) culture created by Europeans with their cult of

sensuality and secret atmosphere. Summing up, we could say that specifically understood

oriental elements played a very important role in European arts, especially in literature,

paintings and architecture.

Despite this often mixed tradition, the word "Orientalism" carried no negative

connotations after the Second World War. Respected institutions like the Oriental Institute of

Chicago or the London School of Oriental and African Studies carried the term without

reproach. "Oriental" was simply understood as the opposite of "occidental" ('western') and

‘orientalists’ (such as Albert Hourani, Maxime Rodinson, Bernard Lewis, in Poland Józef

Bielawski, Ananiasz Zajączkowski and so on) were viewed only as scholars, experts in

history, culture and religions of Middle East, Indian subcontinent or Far East. Situation

changed with the publication of Edward Said’s book.

2. Edward Said’s vision of orientalism

The word ‘Orientalism’ began to develope negative connotations following the

publication of the crucial work Orientalism by the U.S. based Palestinian scholar Edward R.

Said6. Said’s book is based on describing and critiquing "Orientalism," which he perceived as

One of such „oriental” paintings, Snake charmer by Jean-Leon Gerome was revealed as an illustration on the

title page of Edward Said’s Orientalism. This stereotypical depiction of Islamic culture with a beatiful young boy

dancing among Bedouins illustates very well conceptions of the author.

6

Edward Wadie Said (November 1, 1935 – September 24, 2003) was a well-known Palestinian-American

literary theorist, critic and outspoken pro-Palestinian activist. Said was born in Jerusalem (then in the British

Mandate of Palestine). He joined the faculty of Columbia University in 1963 and served as a professor of

English and Comparative Literature for several decades. Said became the Parr Professor of English and

Comparative Literature at Columbia, in 1977, and subsequently became the Old Dominion Foundation Professor

in the Humanities. In 1992, Said attained the rank of University Professor, which is Columbia's most prestigious

academic position. He also taught at Harvard, John Hopkins, and Yale universities. As a Palestinian activist, Said

campaigned first for a creation of an independent Palestinian state, and then later for a single Jewish-Arab state.

From 1977 until 1991, Said was an independent member of the Palestinian National Council who tended to stay

5

5

a constellation of false assumptions underlying Western attitudes toward the East. Said

described the process which could be called subtle and persistent Eurocentric prejudice

against Arabo-Islamic peoples and their culture7. He argued that a long tradition of false and

romanticized images of Asia and the Middle East in Western culture had served as an implicit

justification for Europe and America's colonial and imperial ambitions. Just as fiercely, he

denounced the practice of Arab elites who internalized the American and British orientalists'

ideas of Arabic culture using colonial practices to justify dictator character of governments. It

is important to mention that Said’s book is concentrated very much on the Arab Middle East

and doesn’t give any material or remarks on the region of Far East. So, in terms of border his

‘orientalism’ is limited geographically as it was practicized during the Middle Ages.

The work begins with two important mottos: They cannot represent themselves; they

must be represented (by Karl Marx) and The East is a career (by Benjamin Disraeli)8. Then,

Said puts forward several definitions of Orientalism in the introduction to Orientalism. Some

of these have been more widely quoted and influential than others:

“Unlike the Americans, the French and British – less so the Germans, Russians,

Spanish, Portuguese, Italians, and Swiss – have had a long tradition of what I shall be

calling Orientalism, a way of coming to terms with the Orient that is based on the

Orient's special place in European Western Experience. The Orient is not only

adjacent to Europe; it is also the place of Europe's greatest and richest and oldest

colonies, the source of its civilizations and languages, its cultural contestant, and one

of its deepest and most recurring images of the Other. In addition, the Orient has

helped to define Europe (or the West) as its contrasting image, idea, personality,

experience. Yet none of this Orient is merely imaginative. The Orient is an integral

part of European material civilization and culture. Orientalism expresses and

represents that part culturally and even ideologically as a a mode of discourse with

out of factional struggles, the author of important works as Orientalism (1978), Culture and Imperialism (1993),

Reflections on Exile (2001).

7

Compare: entry Edward Said in: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia [Internet:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orientalism, May 2006].

8

Edward W. Said, Orientalism. Western Conceptions of the Orient, Penguin Books, London 1991, page XIV.

6

supporting institutions, vocabulary, scholarship, imagery, doctrines, even colonial

bureaucracies and colonial styles (...)

It will be clear to the reader...that by Orientalism I mean several things, all of them, in

my opinion, interdependent. The most readily accepted designation for Orientalism is

an academic one, and indeed the label still serves in a number of academic institutions.

Anyone who teaches, writes about, or researches the Orient – and this applies whether

the person is an anthropologist, sociologist, historian, or philologist – either in its

specific or its general aspects, is an Orientalist, and what he or she says or does is

Orientalism (...)

Related to this academic tradition, whose fortunes, transmigrations, specializations,

and transmissions are in part the subject of this study, is a more general meaning for

Orientalism. Orientalism is a style of thought based upon ontological and

epistemological distinction made between ‘the Orient’ and (most of the time) ‘the

Occident’. Thus a very large mass of writers, among who are poets, novelists,

philosophers, political theorists, economists, and imperial administrators, have

accepted the basic distinction between East and West as the starting point for elaborate

accounts concerning the Orient, its people, customs, "mind," destiny, and so on. (...)

(...) in short, Orientalism as a Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having

authority over the Orient.(...)

Therefore, Orientalism is not a mere political subject matter or field that is reflected

passively by culture, scholarship, or institutions(...). It is rather a distribution of

geopolitical awareness into aesthetic, scholarly, economic, sociological, historical, and

philological texts; it is an elaboration not only of a basic geographical distinction (the

word is made up of two unequal halves, Orient and Occident) but also of a whole

series of ”interests” which, by such means as scholarly discovery, philological

reconstruction, psychological analysis, landscape and sociological description, it not

only creates but maintains.”9

9

Ibidem, pages 1, 2, 3, 12.

7

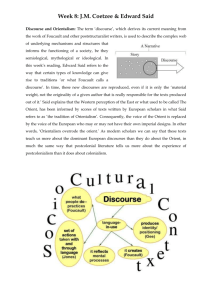

These long but necessary citations illustrate Said’s approach that is interdiscipinar

combining analysis of literature, paintings and scientific dissertations with radically critical

character of his thinking. Taking his cue from the work of Jacques Derrida and Michel

Foucault (acknowledging the influence of the latter, but not the former), and from earlier

critics of western Orientalism such as A.L. Tibawi, who analyzed traditional visions of Arab

nationalism in European scientific literature, Said argued that all Western writings on the

Orient, and the perceptions of the East purveyed in them, are suspect, and cannot be taken at

face value. According to Said, the history of European colonial rule and political domination

over the East distorts the writings of even the most knowledgeable, well-meaning and

sympathetic Western ‘Orientalists’ (a term which he transformed into a pejorative epithet)

such as British Arabist Bernard Lewis . He argues that their claims to objective knowledge of

the Orient are simply claims to power.

“I doubt if it is controversial, for example, to say that an Englishman in India or Egypt

in the later nineteenth century took an interest in those countries which was never far

from their status in his mind as British colonies. To say this may seem quite different

from saying that all academic knowledge about India and Egypt is somehow tinged

and impressed with, violated by, the gross political fact – and yet that is what I am

saying in this study of Orientalism”.10

Edward Said’s analysis locates somewhere in the sphere of postmodern reflection, that

is related to Foucault’s ‘relation of power and oppression’. If Foucault wrote a lot about

oppression in terms of human’s sexuality, Said concentrates on relations between colonizer

and colonized, translates mechanisms of colonial discourse that are still actual (in Said’s view

American and Israeli strategies of propaganda continue experiences of British and French

colonialism). Even if Said’s book utilizes methods or approaches mainly rooted in theory of

literature and cultural studies (postcolonial studies), it can be useful for contemporary social

theory too. If postmodern paradigm of contemporary social theory does exist (what is not

certain), Orientalism could be seen as one of its examples. Total lack of respect for

boundaries between traditional scientific disciplines, usage of analysis of literature for

purposes of social critic – these factors make Said’s work convenient for postmodern

discourse.

10

Ibidem, page 11.

8

Said’s contention was that Europe had dominated Asia politically so completely for so

long, that in Orientalist writings a very considerable bias exists in even the most outwardly

objective of texts, a bias which most Western scholars would not even be able to recognise,

because it is part of their cultural make-up too. His contention was that the West has not only

conquered the East politically, but that Western scholars have appropriated the exploration

and interpretation of the Orient’s languages, history and culture for themselves. They have

written Asia’s past and constructed its myriad modern identities from a perspective which

takes Europe as the norm from which the ‘exotic’, ‘inscrutable’ Orient deviates. Said

concludes that Western writings about the Orient invariably depict it as an irrational, weak,

feminised ‘Other’, contrasted with the rational, strong, masculine West. Western writings are

about creating ‘difference’ between West and East, a difference which is attributed to the

existence of certain ‘essences’ in the Oriental make-up11. Having thus stated his central thesis,

the remainder of Orientalism consists mainly of examples from Western texts designed to

illustrate it. There is a mixture of different texts that there are under scrutiny: classical works

of Silvestre de Sacy and Ernest Renan, speeches of British politicians and colonial oficers as

Lord Cromer and Arthur James Balfour, famous Description of Egypt connected with

Bonaparte’s conquest of Egypt, memoirs of T.H. Lawrence and new orientalistic volumes

commenting Israeli nad American policy toward Arab communities.

Said’s work despite of many superb passages containing analysis of sources

demonstrates a big tendention to essentialize and homogenize the West and Western culture,

politics and science. The fiercest criticism of his views has come from academic orientalists

such as British arabist Bernard Lewis, historian of Middle East and Islam Albert Hourani and

Iraqi American specialist in political sciences Kanan Makiya who feel that their profession

has been unfairly treated and mystified. Bernard Lewis was among the scholars whose work

Said questioned in Orientalism and subsequent works. Other scholars, such as Maxime

Rodinson, Jacques Berque, Malcolm Kerr, Aijaz Ahmad and William Montgomery Watt also

regarded Orientalism as a deeply flawed account of Western scholarship

Said's academic critics argued that Said made no attempt to distinguish between the

writings of poets such as Goethe (who never even travelled in the East), novelists such as

Flaubert (who undertook a brief sojourn in Egypt), controversial scholars such as Ernest

11

Compare: entry Edward Said in: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia [Internet:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orientalism, May 2006].

9

Renan, and serious Orient researchers such as Edward William Lane who were fluent in

Arabic and produced work of considerable value: their common European origins and

attitudes, according to Said, overrode such considerations. Furthermore, Robert Irwin

(amongst others) has pointed out that Said had entirely ignored the fact that Oriental studies in

the 19th century were dominated by Germans and Hungarians, from countries which,

inconveniently for Said's purposes, did not possess an Eastern Empire12. Said is further

accused of creating a monolithic ‘Occidentalism’ to oppose to the ‘Orientalism’ of Western

discourse: he failed to make a distinction between Romanticism and Enlightenment thinking,

he ignored the widespread and fundamental differences of opinion amongst western scholars

of the Orient; he failed to acknowledge that many Orientalists (such as Sir William Jones)

were more concerned with establishing kinship between East and West than in creating

‘difference’, and had frequently made discoveries which would provide the foundations for

anti-colonial nationalism (even colonial excavations in Egypt could develope paradoxically

political consciousness of local Arab populations!). More generally, Said and his followers

have been criticised for making no distinction between Orientalism in the media and popular

culture and the work of Western scholars.

Finally, Said's critics argue that by making ethnicity and cultural background the test

of authority and objectivity in studying the Orient, Said drew attention to the question of his

own identity as a Palestinian, and as an American. Given his prominent position at the heart

of the American Academy (he was at one time President of the Modern Language

Association), his largely Anglophone upbringing and education at an elite school in Cairo,

and the fact that he spent his entire adult life in the United States, if one accepts Said's own

arguments that all representations are embedded in language and culture, it could

paradoxically suggest that he himself is also a representant of Orientalism. Said was also

criticized more generally for his and excessive using of ‘representation’ as crucial category

what is rather a kind of general criticism concerning ‘postmodern relativism’

Said’s supporters argue that these criticisms, even if correct, do not invalidate his basic

thesis, which still holds true for the 19th and 20th centuries and in particular for general

representations of the Orient in Western media, literature and film. They point out that Said

himself had acknowledged the limitations of his study in failing to address German

12

Citation from Robert Irwin, For Lust of knowing: The Orientalists and their enemies, Allen Lane, London

2006 pp159-160, 281-2822, taken from: entry Edward Said in: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia [Internet:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orientalism, May 2006].

10

scholarship, and that in the 'Afterword' to the 1995 edition of his book he had convincingly (to

them) refuted his critics such as Bernard Lewis. Apart from his continuing importance in the

fields of literary criticism and cultural studies, his work has had particular influence on

scholars studying India, such as Gyan Prakash and on literary theorists such as Homi Bhabha

and Gayatri Spivak. Said’s methodology resulted also in some specified researches

concerning relations of power, exclusion and usage of stereotypes in description of social,

religious and ethnical groups, eg Polish social stratification after the collapse of Communist

regime (especially demonization of rural population, as backward, irrational and eager for

despotic forms of government, made by some right-wing and liberal publicists and scholars –

this phenomenon was analyzed by Polish sociologist Piotr Głuchowski who has been

extensively using in his research the term ‘nesting orientalism’ [domowy orientalizm]).

National and religious conflicts in the Balkans were also researched with references to

‘nesting orientalism’.

Said’s critics and supporters alike acknowledge the profound, transformative influence

which Orientalism has had across the spectrum of the Humanities including social sciences

and theory of literature - the former, however, allege that it has been almost wholly negative,

the latter that it was liberating. One of reactions on Said’s argumentation was also discussion

on the very term ‘Occidentalism’ that was often viewed as inversion of Said’s understanding

of ‘Orientalism’.

3. Occidentalism – Western or Eastern tradition?

In contemporary discussion occidentalism is defined as a term for stereotyped and

sometimes dehumanizing views on the so-called Western world, including Europe, the United

States, Australia and even modern Japan. The term was popularized by Ian Buruma and

Avishai Margalit in their book Occidentalism: the West in the Eyes of its Enemies (2004). The

notion was used earlier in some books, but with rather different meanings sometimes even as

a synonym of pro-Western attitude. Still, the term is not clear and even if the mentioned

dissertation works as embodiment of new understanding of occidentalism, there are other

explanations.

11

Ian Buruma – a professor of human rights, democracy and new media studies at Bard

College and Avishai Margalit – a professor of philosophy at the Hebrew University in

Jerusalem prepared interdisciplinar research that is in some way quite similar to Said’s

Orientalism. Buruma suggested that the book is not an attack on Edward Said but rather it

echoes his work13, because he did have one profound insight, which is that there was a view

of the non-Western world that was dehumanizing, that depicted non-Western people as less

than morally adult, childlike and cruel, which in some instances did indeed justify Western

imperialism. The idea was not to attack that notion but to show the flip side, that there is an

equally dehumanizing view of the West, or of what its enemies think the West represents.

Buruma defines also problems with understanding of occidentalists:

“The other misunderstanding is that we are somehow talking about critics of the West,

critics of American foreign policy or those who have an aversion to Hollywood

movies. That is not what we are about either. What we identify as Occidentalists are

not simply critics or haters of America or the West at large; it is people with such a

dehumanizing vision of what the West represents that they are prepared to commit

colossal violence and mass murder to further their ends. That is when it begins to

interest us”14

Buruma and Margalit argue that nationalist and nativist resistance to the West actually

replicates responses to forces of modernisation that have their roots in Western culture itself,

among both utopian radicals and nationalist conservatives who saw capitalism, liberalism and

secularism as destructive forces. They argue that while early responses to the West represent a

genuine encounter between alien cultures, many of the later manifestations of occidentalism

betray the influence on Eastern intellectuals of Western ideas, such as the supremacy of the

nation-state, the Romantic rejection of rationality and the alleged spiritual impoverishment of

the citizens of liberal democracies. They trace this to German Romanticism and to the debates

between the "Westernisers" and "Slavophiles" in 19th century Russia, asserting that similar

Ian Buruma, The Origins of Occidentalism, „The Chronicle”, 2th of June 2004 [Internet:

http://chronicle.com/free/v50/i22/22b01001.htm, May 2006].

14

Ian Buruma, Occidentalism: The West in the Eyes of Its Enemies, Edited transcript of remarks, 4/8/04,

Discussion in Carnegie Council Books (Merrill House, New York City) [Internet:

http://www.cceia.org/viewMedia.php/prmID/4465, May 2006].

13

12

arguments appear under differing guises in Maoism, Islamism, wartime Japanese nationalism

and other movements. Authors’ approach is presented in such definitions:

“Clearly, the idea of the West as a malign force is not some Eastern or Middle Eastern

idea, but has deep roots in European soil. Defining it in historical terms is not a simple

matter. Occidentalism was part of the counter-Enlightenment, to be sure, but also of

the reaction against industrialization. Some Marxists have been attracted to it, but so,

of course, have their enemies on the far right. Occidentalism is a revolt against

rationalism (the cold, mechanical West, the machine civilization) and secularism, but

also against individualism. European colonialism provoked Occidentalism, and so

does global capitalism today. But one can speak of Occidentalism only when the revolt

against the West becomes a form of pure destruction, when the West is depicted as

less than human, when rebellion means murder.

Wherever it occurs, Occidentalism is fed by a sense of humiliation, of defeat. Isaiah

Berlin once described the German revolt against Napoleon as <the original exemplar

of the reaction of many a backward, exploited, or at any rate patronized society, which,

resentful of the apparent inferiority of its status, reacted by turning to real or imaginary

triumphs and glories in its past, or enviable attributes of its own national or cultural

character>"15.

Methodology of Occidentalism: the West in the Eyes of its Enemies is as controversial

as it was in the case of Said. Examples create a mixture of many elements from different

cultures and historical periods.Western predecessors of Occidentalism as Oswald Spengler,

Aurel Kolnai and Houston Stewart Chamberlain are followed by radical left-wing

theoreticians (Frantz Fanon) and original Oriental scholars and politicians. For example,

Buruma and Margalit classify as Occidentalists supporters of such differentiated political

currents as Islamic fundamentalism (Sayyid Qutb) and Arab secular nationalism (Sati al-

Ian Buruma, The Origins of Occidentalism, „The Chronicle”, 2th of June 2004 [Internet: http://The Chronicle

2-6-2004 The Origins of Occidentalism.htm].

15

13

Husri)16. That’s true that these two approaches represent deep anti-Western sentiments but

their ideological approach is competely different and inside Middle Eastern societies

supporters of both attitudes are in the radical conflict. Despite of these controversial points we

could say that Buruma’s and Margalit’s view of Oriental literature on the West is not as

essential nad monolithic as Said’s interpretation of Western approaches to Orient. In one of

his seminars Buruma criticized the conception of the clash of civilizations:

“As far as the clash of civilizations, I am not a Huntingtonian. This is not a

fundamental clash of one civilization against another, because Al-Qa’ida does not

represent the Middle East or Arabs or Muslims any more than the Christian Coalition

or Southern Baptists represent the West. After all, in the West itself there are forms of

religious fundamentalism which are disturbing.

What I have described about Al-Qa’ida you can see in completely different cultural

contexts. Al-Qa’ida's visions remind me of the Aum Shinrikyo in Japan, the group of

quasi-Buddhists — often engineers and people from technical universities, who felt

that modern Japanese society was empty, without spirit, without soul, machine-like –

who wanted to foment a religious revolution to create a purer society. They had views

of Armageddon that are not so different from that of certain kinds of Christian

extremists”17.

Huntingtonian theory is often criticized as an example of ‘orientalism’ in Said’s sense

with its static vision of civilizations and utopian conviction about creation of IslamicConfucian connection in the future. Stein Tonnesson writes that Huntington’s approach is one

of possible ways of relation to the question East versus West in contemporary world. The

second option is the opposite one: to engage in intellectual critics of Western domination from

cultural and ethical perspective and it is the case of Said. The next possibility is Eastern

reaction on Western discourse and this approach is called by Tonnesson ‘occidentalism’18. It

is defined as “positive Arab response to Edward Said's critique of Western Orientalism”, so it

differs a lot from Buruma and Margalit’s approach.

Ian Buruma, Avishai Margalit, Okcydentalizm. Zachód w oczach wrogów, w przekładzie Adama Lipszyca,

Universitas, Kraków 2005, s. 146-149.

17

Ian Buruma, Occidentalism: The West in the Eyes of Its Enemies, Edited transcript of remarks, 4/8/04,

Discussion in Carnegie Council Books (Merrill House, New York City) [Internet:

http://www.cceia.org/viewMedia.php/prmID/4465, May 2006].

18

Stein Tonnesson, Orientalism, Occidentalism and Knowing about Others [Internet:

http://www.wmich.edu/dialogues/texts/orientalism.htm, May 2006].

16

14

The man who could be seen as a leader of this concept is professor Hassan Hanafi,

leader of the Institute of Philosophy of the University of Cairo and a former researcher at the

United Nations University in Tokyo. In 1992 he published a book about Occidentalism in

Arabic (Muqaddima fi ilm al-Istighrab [Introduction to the Science of Occidentalism,

Westernism]). Hanafi's project is to depict the Occident in the same way that Westerners used

to do it with the Orient with the purpose of recreating an independent Arabic intellectual

tradition (that is connected, as an example, with Ibn Khaldun, Medieval scholar who is

sometimes perceived as the father of modern Western sociology). Arabs must learn to

interpret the West the same way one does it with mice in the laboratory19. Hanafi believes that

the West is in decline. Asked about Francis Fukuyama's claim that History has come to its end,

Hanafi answers: “For Arabs, Africans, Latin-Americans, Asians, History has not ended. It has

perhaps not even started”20. History does not coincide in East and West. For Arabs, the

period that Westerners call “middle age” was the real Antiquity (Arabs call the period of

Caliphates – especially between 7th and 11th centuries – “the golden age of Arabs and Islam).

Now there is time for a renaissance.

Arabs, however, according to Hanafi can be creative if only they are liberated from the

mythical domination of the West, from the complex of being weak and inferior. Arabs must

not be fooled by the idea of a universal culture. The idea of a universal culture is a myth

destined to fool the dominated. This has been done by the ancient Egyptian civilization, later

by the Chinese, Hindus and by the Occident. Hanafi's project is to desanctify in the eyes of

the Arabs the Western gods: Kant, Hegel and Marx who are also the prophets of Arab

nationalism and socialism.

This example illustrates how ‘Occidentalism” can be understood in the reality of

postcolonial Arab science (but also we have to remember that it is European Tonnesson who

labels Hanafi’s work). The term itself became very popular in European and non-European

scientific discourse, there are dissertations and collections of essays concerning different

aspects and meanings of occidentalism eg Deborah Reed-Danahay’s essay on Occidentalism

19

20

Ibidem.

Ibidem.

15

in Bourdieu’s theory of practice (with the importance of opposition French-Kabyle) or Robert

Thornton’s article on the creation and imagining of ‘European” in Southern Africa21.

Thus, terms ‘Orientalism’ and ‘Occidentalism’ has had real impact on contemporary

social sciences. Said’s radical analysis, mainly associated with literature theory and cultural

studies, was important also for anthropologists, sociologists and specialists in political

sciences. Despite of criticism the work Orientalism was crucial in understanding that science

can represent tradition of cultural domination and that real exchange of ideas and

development of different East-West relationships has to be based on equality and mutual

respect. The discussion concerning Said’s book and its critics was not present only in Europe

but also in the Middle East and South Eastern Asia, colonial discourse was researched not

only by Western scholars, there were publications concerning this topic in Japan, Singapore,

India and other countries .

I’d like to finish my brief essay with the citation from Culture and Imperialism by

Edward Said that recapitulates dangers connected with postcolonial heritage, nationalistic

identities and homogenous descriptions of civilizations and cultures. Said’s words give

impression that experience of colonialism (and war with colonialism) infected colonized

people to the extent that contemporarily they can build their countries only on the idea of

exclusive nationalism, intolerance and oppression. .

“My Arab environment had been largely colonial, but as I was growing up you could

travel overland from Lebanon and Syria through Palestine to Egypt and points west.

Today that is impossible .... The past wasn't better, but it was more healthily

interlinked, so to speak; people were actually connected to one another, rather than

staring at one another over fortified frontiers. In many schools you would encounter

Arabs from everywhere, Muslims and Christians, plus Armenians, Jews, Greeks,

Italians, Indians, Iranians, all mixed up, all under one or another colonial regime, but

interacting as if it were natural to do so. .... The effort to homogenize and isolate

21

Two mentioned essays are contained in the collection: Occidentalism. Images of the West, ed. James G.

Carrier, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1995.

16

populations in the name of nationalism (not liberation) has led to colossal sacrifices

and failures .... Identity, always identity, over and above knowing about others”22.

22

Citation taken from: Stein Tonnesson, Orientalism, Occidentalism and Knowing about Others [Internet:

http://www.wmich.edu/dialogues/texts/orientalism.htm, May 2006].

17