Harlem Shadows - Humble Independent School District

advertisement

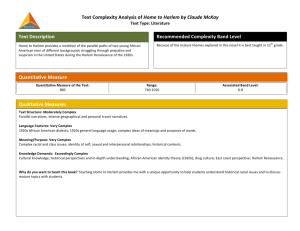

“Harlem Shadows” “Harlem Shadows” – Claude McKay (Poet’s Life) Festus Claudius McKay, better known as Claude McKay, was a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance, a prominent literary movement of the 1920s. His work ranged from vernacular verse celebrating peasant life in Jamaica to fairly militant poems challenging white authority in America, and from generally straightforward tales of black life in both Jamaica and America to more philosophically ambitious fiction addressing instinctual/intellectual duality, which McKay found central to the black individual's efforts to cope in a racist society. Consistent in his various writings is his disdain for racism and the sense that bigotry's implicit stupidity renders its adherents pitiable as well as loathsome. As Arthur D. Drayton wrote in his essay "Claude McKay's Human Pity" (included by editor Ulli Beier in the volume Introduction to African Literature): "McKay does not seek to hide his bitterness. But having preserved his vision as poet and his status as a human being, he can transcend bitterness. In seeing . . . the significance of the Negro for mankind as a whole, he is at once protesting as a Negro and uttering a cry for the race of mankind as a member of that race. His human pity was the foundation that made all this possible." McKay was born in Sunny Ville, Jamaica, in 1889. The son of peasant farmers, he was infused with racial pride and a great sense of his African heritage. His early literary interests, though, were in English poetry. Under the tutelage of his brother, schoolteacher Uriah Theophilus McKay, and a neighboring Englishman, Walter Jekyll, McKay studied the British masters—including John Milton, Alexander Pope, and the later Romantics—and European philosophers such as eminent pessimist Arthur Schopenhauer, whose works Jekyll was then translating from German into English. It was Jekyll who advised aspiring poet McKay to cease mimicking the English poets and begin producing verse in Jamaican dialect. At age seventeen McKay departed from Sunny Ville to apprentice as a woodworker in Brown's Town. But he studied there only briefly before leaving to work as a constable in the Jamaican capital, Kingston. In Kingston he experienced and encountered extensive racism, probably for the first time in his life. His native Sunny Ville was predominantly populated by blacks, but in substantially white Kingston blacks were considered inferior and capable of only menial tasks. McKay quickly grew disgusted with the city's bigoted society, and within one year he returned home to Sunny Ville. During his brief stays in Brown's Town and Kingston McKay continued writing poetry, and once back in Sunny Ville, with Jekyll's encouragement, he published the verse collections Songs of Jamaica and Constab Ballads in London in 1912. In these two volumes McKay portrays opposing aspects of black life in Jamaica. Songs of Jamaica presents an almost celebratory portrait of peasant life, with poems addressing subjects such as the peaceful death of McKay's mother and the black people's ties to the Jamaican land. Constab Ballads, however, presents a substantially bleaker perspective on the plight of Jamaican blacks and contains several poems explicitly critical of life in urban Kingston. Writing in The Negro Novel in America, Robert Bone noted the differing sentiments of the two collections, but he also contended that the volumes share a sense of directness and refreshing candor. He wrote: "These first two volumes are already marked by a sharpness of vision, an inborn realism, and a freshness which provides a pleasing contrast with the conventionality which, at this time, prevails among the black poets of the United States." For Songs of Jamaica McKay received an award and stipend from the Jamaican Institute of Arts and Sciences. He used the money to finance a trip to America, and in 1912 he arrived in South Carolina. He then traveled to Alabama and enrolled at the Tuskegee Institute, where he studied for approximately two months before transferring to Kansas State College. In 1914 he left school entirely for New York City and worked various menial jobs. As in Kingston, McKay encountered racism in New York City, and that racism compelled him to continue writing poetry. In 1917, under the pseudonym Eli Edwards, McKay published two poems in the periodical Seven Arts. His verses were discovered by critic Frank Hattis, who then included some of McKay's other poems in Pearson's Magazine. Among McKay's most famous poems from this period is "To the White Fiends," a vitriolic challenge to white oppressors and bigots. A few years later McKay befriended Max Eastman, communist sympathizer and editor of the magazine Liberator. McKay published more poems in Eastman's magazine, notably the inspirational "If We Must Die," which defended black rights and threatened retaliation for prejudice and abuse. "Like men we'll face the murderous, cowardly pack," McKay wrote, "Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!" In Black Poets of the United States, Jean Wagner noted that "If We Must Die" transcends specifics of race and is widely prized as an inspiration to persecuted people throughout the world. "Along with the will to resistance of black Americans that it expresses," Wagner wrote, "it voices also the will of oppressed people of every age who, whatever their race and wherever their region, are fighting with their backs against the wall to win their freedom." Upon publication of "If We Must Die" McKay commenced two years of travel and work abroad. He spent part of 1919 in Holland and Belgium, then moved to London and worked on the periodical Workers' Dreadnought. In 1920 he published his third verse collection, Spring in New Hampshire, which was notable for containing "Harlem Shadows," a poem about the plight of black prostitutes in the degrading urban environment. McKay used this poem, which symbolically presents the degradation of the entire black race, as the title for a subsequent collection. McKay returned to the United States in 1921 and involved himself in various social causes. The next year he published Harlem Shadows, a collection from previous volumes and periodicals publications. This work contains many of his most acclaimed poems— including "If We Must Die"—and assured his stature as a leading member of the literary movement referred to as the Harlem Renaissance. He capitalized on his acclaim by redoubling his efforts on behalf of blacks and laborers: he became involved in the Universal Negro Improvement Association and produced several articles for its publication, Negro World, and he traveled to the Soviet Union which he had previously visited with Eastman, and attended the Communist Party's Fourth Congress. Eventually McKay went to Paris, where he developed a severe respiratory infection and supported himself intermittently by working as an artist's model. His infection eventually necessitated his hospitalization, but after recovering he resumed traveling, and for the next eleven years he toured Europe and portions of northern Africa. During this period he also published three novels and a short story collection. The first novel, Home to Harlem, may be his most recognized title. Published in 1928, it concerns a black soldier—Jake— who abruptly abandons his military duties and returns home to Harlem. Jake represents, in rather overt fashion, the instinctual aspect of the individual, and his ability to remain true to his feelings enables him to find happiness with a former prostitute, Felice. Juxtaposed with Jake's behavior is that of Ray, an aspiring writer burdened with despair. His sense of bleakness derives largely from his intellectualized perspective, and it eventually compels him to leave alien, racist America for his homeland of Haiti. In The Negro Novel in America, Robert Bone wrote that the predominantly instinctual Jake and the intellectual Ray "represent different ways of rebelling against Western civilization." Bone added, however, that McKay was not entirely successful in articulating his protagonists' relationships in white society. He declared that Home to Harlem was "unable to develop its primary conflict" and thus "bogs down in the secondary contrast between Jake and Ray." The novel also provides a detailed portrayal of the underside of black urban life, with its prostitutes and gamblers, and McKay was applauded for creating "a work of vivid social realism," according to Alan L. McLeod in the Dictionary of Literary Biography. However, McKay himself "stressed that he aimed at emotional realism—he wanted to highlight his characters' feelings rather than their social circumstances," McLeod continued. Nevertheless, it was his glimpse into the "unsavory aspects of New York black life" that was prized by readers—and condemned by such prominent black leaders as W. E. B. Du Bois. Home to Harlem—with its sordid, occasionally harrowing scenes of ghetto life—proved extremely popular, and it gained recognition as the first commercially successful novel by a black writer. McKay quickly followed it with Banjo: A Story without a Plot, a novel about a black vagabond living in the French port of Marseilles. Like Jake from Home to Harlem, protagonist Banjo embodies the largely instinctual way of living, though he is considerably more enterprising and quick-witted than the earlier character. Ray, the intellectual from Home to Harlem, also appears in Banjo. His plight is that of many struggling artists who are compelled by social circumstances to support themselves with conventional employment. Both Banjo and Ray are perpetually dissatisfied and disturbed by their limited roles in white society, and by the end of the novel the men are prepared to depart from Marseilles. Banjo failed to match the acclaim and commercial success of Home to Harlem, but it confirmed McKay's reputation as a serious, provocative artist. "It was apparent to critics that McKay's imagination had been somewhat strained and that the novel was essentially an autobiographical exercise," McLeod remarked. Commentators have found the autobiographical thread in Home to Harlem and Banjo primarily in the character of Ray, whose peripatetic existence to some extent mirrors the author's own, as does the character's admiration for the beauty of young men's bodies. Patti Cappel Swartz digs for clues to McKay's sexuality in the author's fictional works, and points to a dream sequence in Home to Harlem and the fact that "for Ray, the bonds with men will always supersede those with women," as is shown in the conclusion of Banjo. "Like McKay, Ray is not the marrying kind, but rather the vagabond who must always travel on," Swartz continued. In his third novel, Banana Bottom, McKay presented a more incisive exploration of his principal theme, the black individual's quest for cultural identity in a white society. Banana Bottom recounts the experiences of a Jamaican peasant girl, Bita, who is adopted by white missionaries after suffering a rape. Bita's new providers try to impose their cultural values on her by introducing her to organized Christianity and the British educational system. Their actions culminate in a horribly bungled attempt to arrange Bita's marriage to an aspiring minister. The prospective groom is exposed as a sexual aberrant, whereupon Bita flees white society. She eventually marries a drayman, Jubban, and raises their child in an idealized peasant Jamaican environment. "Bita has pride in blackness, is free of hypocrisy, and is independent and discerning in her values," remarked McLeod. "Praise for Banana Bottom has been unanimous." Critics agree that Banana Bottom is McKay's most skillful delineation of the black individual's predicament in white society. Unfortunately, the novel's thematic worth was largely ignored when the book first appeared in 1933. Positive reviews of the time were related to McKay's extraordinary evocation of the Jamaican tropics and his mastery of melodrama. In the ensuing years, though, Banana Bottom has gained increasing acknowledgement as McKay's finest fiction and the culmination of his efforts to articulate his own tension and unease through the novel. McKay's other noteworthy fiction publication during his final years abroad was Gingertown, a collection of twelve short stories. Six of the tales are devoted to Harlem life, and they reveal McKay's preoccupation with black exploitation and humiliation. Other tales are set in Jamaica and even in North Africa, McKay's last foreign home before he returned to the United States in the mid-1930s. Once back in Harlem he began an autobiographical work, A Long Way from Home, in which he related his own problems as a black individual in a white society. The book is considered unreliable as material for his autobiography because, for example, in it McKay denies his membership in the communist party, as McLeod points out. However, A Long Way from Home does state McKay's longheld belief that American blacks should unite in the struggle against colonialism, segregation, and oppression. By the late 1930s McKay had developed a keen interest in Catholicism. Through Ellen Tarry, who wrote children's books, he became active in Harlem's Friendship House. His newfound religious interest, together with his observations and experiences at the Friendship House, inspired his essay collection, Harlem: Negro Metropolis, which offers an account of the black community in Harlem during the 1920s and 1930s. Like Banjo, Banana Bottom, and Gingertown, Harlem: Negro Metropolis failed to spark much interest from a reading public that was a tiring of literature by and about blacks. Critic McLeod offers a more recent evaluation of the work, the writing of which was based as much on scholarly inquiry as on personal observation, as McKay was absent from the country for a good deal of the period covered: "The book has been superseded by many more-scholarly studies, yet it retains value as a reexamination of Harlem by one who had established a necessary critical distance." With his reputation already waning, McKay moved to Chicago and worked as a teacher for a Catholic organization. By the mid-1940s his health had deteriorated. He endured several illnesses throughout his last years and eventually died of heart failure in May 1948. In the years immediately following his death McKay's reputation continued to decline as critics found him conventional and somewhat shallow. Recently, however, McKay has gained recognition for his intense commitment to expressing the predicament of his fellow blacks, and he is now admired for devoting his art and life to social protest. As Robert A. Smith wrote in his Phylon publication, "Claude McKay: An Essay in Criticism": "Although he was frequently concerned with the race problem, his style is basically lucid. One feels disinclined to believe that the medium which he chose was too small, or too large for his message. He has been heard." McKay continues to be associated with the phenomenon known as the Harlem Renaissance, though he lived outside of the country for much of the period, and has found new audiences among readers of commonwealth literature and gay and lesbian literature. McLeod concluded his essay in Dictionary of Literary Biography with the following accolades: "That he was able to capture a universality of sentiment in 'If We Must Die' has been fully demonstrated; that he was able to show new directions for the black novel is now acknowledged; and that he is rightly regarded as one of the harbingers of (if not one of the participants in) the Harlem Renaissance is undisputed." Career Writer. Worked as cabinetmaker's apprentice and wheelwright; constable, Jamaican Constabulary, Kingston, Jamaica, 1909; longshoreman, porter, bartender, and waiter, 1910-14; restaurateur, 1914; writer for Pearsons Magazine, 1918, and Workers' Dreadnought in London, England, 1919; associate editor of Liberator, 1921; American Workers representative at Third International in Moscow, U.S.S.R., 1922; artist's model in mid-1920s; worked for Rex Ingram's film studio in France, c. 1926; shipyard worker, c. 1941; worked with the National Catholic Youth Association, 1944-48. Source Citation: Go to Poetryfoundation.org to find the source citation. “Harlem Shadows” – Claude McKay (Historical Events) Historical Events In 1951, when “Harlem” was first published, race relations were much different in the United States than they are today. Racism still exists, but there are now laws that can be used to fight against discrimination. Most of these laws were enacted during a period from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s, when blacks became impatient with deferring their dreams and whites, especially in the Southern states, resisted the social forces that were pushing for equality. The Civil War ended in 1865, and with its end, slavery became extinct in the United States, but the freed blacks did not receive full citizenship status. In the late 1800s, former slave states passed a series of laws known as Jim Crow laws (after a foolish, childlike Negro character in an 1832 minstrel comedy). These laws made it illegal for blacks to vote, ride public transportation, attend schools with whites, and other functions that would have enabled African Americans to become equal members of society. Although many citizens opposed these laws, especially in the North where there had been no slavery, the Supreme Court ruled in 1886 that they were constitutional so long as blacks had facilities similar to those of whites. In that case, Plessy vs. Ferguson, the court ruled that the legality of Jim Crow laws rested upon there being “separate but equal” accommodations for both races: in reality, though, blacks were given the worst of everything. To keep blacks from gaining political power, there were other laws that made it difficult to register to vote, requiring land ownership and passage of bogus I.Q. tests that were seldom administered to caucasians. Many African Americans moved North, where laws did not discriminate, even though people still did. Opportunities for advancement were still scarce in the North, mainly because of the economic/educational circle (undereducated people cannot get well-paying jobs, and people with poor incomes cannot afford higher education). In the South in the first half of this century, blacks were lynched by white supremacist organizations, such as the Ku Klux Klan. During World War II, from 1941 to 1945, the armed forces became the most integrated organization that the United States had ever had. Although it would still be decades until blacks were admitted to the higher ranks of officers, opportunity was, to a wide extent, equal among enlisted men. This meant that returning veterans came home with a greater sense of how racial equality was possible, raising hopes for integration in whites as well as in blacks. These hopes sometimes twisted into anger when black veterans found civilian society a step backwards from their life in the army: full scale riots broke out in 1946 in Columbia, Tennessee, and Athens, Alabama, as well as lesser racial confrontations in dozens of other cities. As the call for a new racial openness in the United States grew, though, another social force was also growing: fear of the threat of Communism. World War II had weakened or destroyed most of the powerful European nations and left the Soviet Union as the only other world power with might that could compare to the United States. The two counties had different social philosophies and each was afraid that the other would plant spies in its government or its media to cause its collapse. These techniques were tried by both sides, but not nearly to the degree that citizens feared them. In the South, the public’s fear of Communism was used by some whites to oppose integration. In the Presidential election of 1948, for example, Democrat Harry Truman and Republican Thomas Dewey were opposed by southern Senator Strom Thurmond, with the newly formed States Rights Democratic party. Thurmond claimed that regular Democrats supported civil rights due to their “Communist ideology,” arguing that Democrats intended to “excite race and class hatred” and “create chaos and confusion which leads to communism.” Truman just barely won the election. In 1948, by an Executive Order from the President, a commission was established to study equal treatment in the armed forces. Historians believe that the committee’s recommendations would have pushed integration further if the country had not become involved in the Korean Conflict to stop the spread of Communism. As it was, proposals made in 1949 by the Truman administration regarding racial issues like lynchings and voter registration were held up in Congress until the Civil Rights Act of 1957. Source Citation: "Harlem." Poetry for Students. Ed. Marie Rose Napierkowski. Vol. 1. Detroit: Gale, 1998. 61-73. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 26 Jan. 2012. “Harlem Shadows” – Claude McKay (Criticism) Though James Weldon Johnson wrote justly that Claude McKay was “one of the principal forces in bringing about the Negro literary awakening” that came to be called the Harlem Renaissance (Johnson 168; Maxwell xxi), it is equally just to observe that “the extreme traditionalism of his poetry” expresses his literary education in the work of William Shakespeare and many other British poets (Giles 44)—McKay himself names “Childe Harold, The Dunciad, Essay on Man, Paradise Lost, [and] the Elizabethan lyrics” as those most influential on his own artistry (A Long Way From Home 13).1 While other poets and critics have faulted McKay’s poetry for its apparently conservative use of British forms of versification (see, e.g., Brathwaite 19–20), William J. Maxwell has shown how his use of that meter and of conventional end-rhymes, like his use of standard English after his youthful dialect-poetry, “met the need for a medium of expanded radical communication” (Maxwell xxxii).McKay himselfwrote that he had adopted “such of the older traditions as I find adequate for my most lawless and revolutionary passions and moods” (Author’s Note xx). In McKay’s account, metrical and stanzaic patterns are not prisons but rather (as Houston Baker has said of McKay’s use of the sonnet forms) “mastered masks”—in them, McKay achieves not merely conformity but rather “mastery of form” (85).One example is immediately clear: in “Harlem Shadows,” McKay uses three Venus-and-Adonis stanzas—that is, a six-line stanza in iambic pentameter rhyming ababcc—rather than the three quatrains followed by one couplet that normally constitute an English sonnet. McKay wrote so many sonnets, including those in the English form, that this deviation confirms Baker’s point: McKay displays familiarity and skill with Elizabethan verse forms that are uncommon in modern American poetry. His deviation or inflection in the form of the sonnet also confirms Maxwell’s observation about that artistry’s radical expression: at a glance, his poem is likely to appear to be a sonnet, especially as it is situated amongst so many sonnets in the book Harlem Shadows, but it is a deviant poem in its use of the eighteen lines, organized to recall the form of the sonnet but with a difference. In addition to a shifting of tone and subjectmatter from the traditional tropes of love (as in Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis) to those of McKay’s own place and time—“tired feet” (11), for example, and “fallen race” (16)—McKay finds a formal deviation to match his topical and even “lawless and revolutionary” themes (McKay, Author’s Note in Harlem Shadows xx). In the first line of the poem, the pyrrhic foot (i.e., a foot consisting of two unstressed syllables) is expressive: the fourth foot in this line has no accent at all—the second syllable of “footsteps” is not stressed, and neither is the little preposition “of.” This emptiness of accent matches the “halting” of footsteps, as the alliteration of the h-sounds in lines one and two creates a hush in the night street. The extreme enjambment of line two causes the sentence to fall to the next line, exactly at the word “fall,” but it also embeds the echoing consonance of “fall” and “veil” (line 3). The hard and battering b-alliteration of “bend and barter” in line four is an improvement to the poem that appeared in McKay’s 1922 book Harlem Shadows.2 In its first periodical publication, that line reads more weakly phonetically: “Eager to heed desire’s insistent call” (Maxwell 321n.). All of these techniques at the level of sound-effects lavish poetic attention on the fallen, the weak, and the lowly in “Negro Harlem” (2), concentrating attention and dignity—even sonorous nobility upon the thrice-downtrodden black women in their “poverty, dishonor, and disgrace” (14). What follows that first quatrain is the first iteration of words that conclude each of the three stanzas of the poem. Sir Philip Sidney’s Old Arcadia (often called the Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia) includes among its embedded poems an eighteen-line lyric in the Venus-and-Adonis stanza, “O words which fall like summer dew on me” (p. 266–67). In Sidney’s poem, in the first two stanzas, the last lines both end with the same phrases—not the entirety of each line, but their second halves. Sidney’s stanzas end with the phrase, “to seal this promise due,” and “as I to her am true.” The last two lines in each stanza of “Harlem Shadows” likewise end with the same words in each stanza, while the first half of each line varies. I am not suggesting that McKay is consciously imitating this particular poem of Sidney’s (although that possibility is likely), but rather pointing out the formal effect: echo, repetition, and unity by musical refrain. Again McKay brings the dignity and beauty of Elizabethan forms and techniques to subjects that are not only modern but conspicuously outside the traditional tropes of honored and arcadian loveliness with which McKay’s forms are associated in the literary tradition that he thus appropriates and subverts simultaneously. The musical effect of repetition is also developed much further: the repetition of “girlswho” (3, 5) creates a smaller echoeffect. So too, the repetition of “feet” (in the fifth line of each stanza) is augmented by its repetition again in line 8. There, the word is given special emphasis by its location in a spondee (a foot of two syllables, both accented). In the same line, the homonymic repetition of “know no” creates another echo-effect, and so does the larger repetition of the phrase “Through the long night” (7) in the later phrase “Through the lone night” (9). The echoes within the lines mirror the closural repetitions at the ends of the stanzas. McKay’s metrical dexterity and versatility are evident in more than his use of iambic pentameter alone: metrical variants make musical metaphors, as in the third stanza, where two pyrrhic feet in line 14 are as expressive as the pyrrhic foot in the poem’s first line. In the last two syllables in the phrase “Of poverty,” and again in the last two syllables of “dishonor and,” neither syllable receives metrical stress. Absence and emptiness are of course the subject matter and the point of the line, “Of poverty, dishonor and disgrace,” so that the meaning of the sentence mirrors the music of the verse. Vivid, specific, and also as large as the range of human fear, loss, and sympathy, the poem embodies its emotional and ultimately moral themes in the forms—rhythm, alliteration and assonance, pitch of vowels, and pattern of rhyme—that communicate, as poetry can, the bodily as well as artful levels of sense and meaning. The human experiences among the poem’s characters which the poem treats as meaningful not only include the lawless (prostitutes) and the lowly—the poem also sings of their sacredness. Despite the complaints of some of McKay’s later critics, the structures of traditional forms do not apparently imprison the messages of McKay’s poems, but rather set them free.