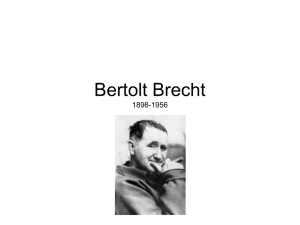

Lesson One - Drama Queensland

advertisement