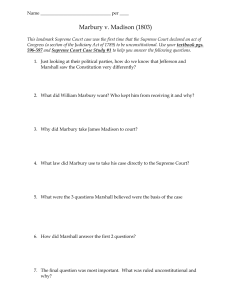

Marbury v Madison

advertisement

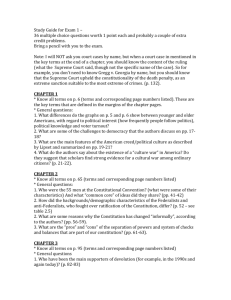

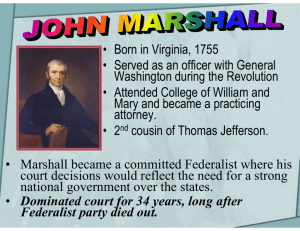

SUBJECT: PATRIOT WEEK DOCUMENTS: DAY TWO Marbury v. Madison Overview of Marybury v. Madison Author(s) Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall; signed by Justices William Paterson, Samuel Chase, and Bushrod Washington Date created/enacted Case argued from February 11, 1803 Case decided February 24, 1803 Content summary The case was fairly simple. In the waning days of his presidency, John Adams appointed 58 new judges and justices of the peace. In order for these appointments to become official, the men selected needed to receive their legal commissions—paperwork showing that they were now judges. Most were delivered. When Thomas Jefferson became president, he instructed his Secretary of State not to deliver the remaining commissions. William Marbury was one of the new justices of the peace who had not received his paperwork, and he sued the Secretary of State, James Madison. Marbury wanted the Supreme Court to issue a writ of mandamus—a command—ordering James Madison to deliver Marbury’s commission. The power to issue such writs had been granted to the Supreme Court by Congress’s Judiciary Act of 1789. In the unanimous decision, Chief Marshall agreed with most of Marbury’s claim: Marbury had a right to the commission, there was a legal remedy for the situation, and a writ of mandamus was a suitable remedy. However, Marshall found that the Supreme Court had no right to issue such a writ, because the power to do so had been inappropriately granted by Congress. This was so because the Constitution specifically states that what kinds of cases the Supreme Court can take. With a few exceptions, the Supreme Court only can take cases on appeal - and the Constitution does not allow the Supreme Court to review a writ of mandamus case except on appeal. In other words, by giving the Supreme Court the power to review the Marbury’s case, it gave the Supreme Court a power not in the Constitution. Congress had passed an unconstitutional law—the Judiciary Act of 1789. Accordingly, the Supreme Court struck down the Judiciary Act of 1789 as unconstitutional, and it became void. Ironically, this landmark case, which firmly established judicial review as a cornerstone power of the Supreme Court, centered on the fact that Congress had granted the Supreme Court too much power. In ruling that his court did not have the power to grant a writ of mandamus, Chief Justice PAGE 1 OF 2 SUBJECT: PATRIOT WEEK DOCUMENTS: DAY TWO Marshall had established for the Court the tremendously greater power of judicial review. The case laid to rest any question about whether the Supreme Court could strike down an act of Congress if Congress passed an unconstitutional law. The case is also important because it established that the Supreme Court would be the branch of government that would finally determine what the Constitution meant and how to interpret the law. Current location The case is published in the official reports of the United States Supreme Court. Objectives 1. Students should understand the Supreme Court determines what the Constitution means. 2. Students should understand that a law the violates the Constitution will be struck down (and become null and void) by the Supreme Court. 3. Students should understand that the Constitution governs what happens in American government - not just what the people or politicians want (and not force or violence). Materials • A concise summary of Marbury v. Madison can be found at http://www.patriotweek.org/marbury-madison.html. Activities 1. When your students feel they’ve been dealt with too harshly, or do not agree with a decision that has been made about them, how do they “appeal” these decisions? To whom or what do they go to redress “wrongs” that have been done against them? 2. What are some other laws that the Supreme Court has found to be unconstitutional? 3. What constitutional cases is the Supreme Court due to hear this year? Contributor Michael DeBruyn (Teacher, Shrine Catholic High School and Academy, Royal Oak, MI) (edited by Hon. Michael Warren) PAGE 2 OF 2