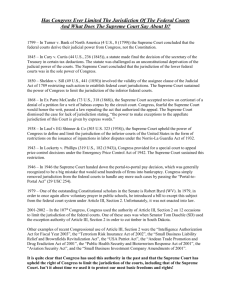

Outline re: CAFA and BOP

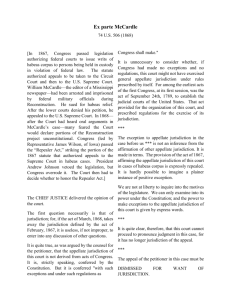

advertisement