Chapter III: DECISION MAKING AND DECISIONAL CAPACITY IN

advertisement

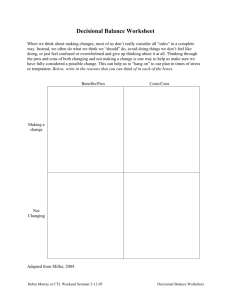

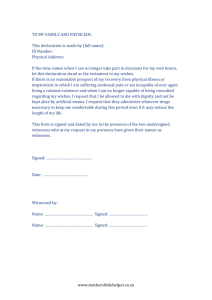

Chapter III: DECISION MAKING AND DECISIONAL CAPACITY IN ADULT PATIENTS • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Health care decisions and decision making Decision-making capacity Capacity and competence Elements of decisional capacity Decision-specific and fluctuating capacity Capacity assessment and determination Importance of capacity determination Clinical standards for decisional capacity Who assesses decisional capacity? Deciding for patients without capacity Background Standards of decision making Decision making for the formerly capacitated Advance directives Deciding for patients without capacity or advance directives Decision making for patients who never had capacity Mrs. K is an 89-year-old woman admitted from home 5 days ago with cellulitis of the legs. Despite her discomfort, she has been cooperative with her diagnostic work-up and treatment, and has consented to all interventions related to the cellulitis. She was able to provide accurate information about her medical history, which was corroborated by her niece. According to both women, Mrs. K has been very healthy and self-sufficient all her life, a state she attributes largely to “keeping my distance from doctors and hospitals.” Her goal, expressed repeatedly since admission, is to “go home and take care of my cats.” Mrs. K’s admission blood tests revealed anemia that suggested slow internal bleeding. Despite repeated attempts to explain the dangers of unchecked bleeding and the importance of identifying the source, she has consistently refused consent for a GI series. When you ask her why she is opposed to a diagnostic work-up, she replies, “Dahling, you look you’ll find. No more tests or treatments. Just get me back on my feet so I can go home to my cats.” After several days, the attending physician requests a psychiatric consult to do a capacity assessment. He suggests that the patient is not capable of making decisions in her best interest and cannot be discharged under these circumstances. You wonder why no one questions Mrs. K’s capacity to consent to treatment, only her capacity to refuse. Introduction Ethical principles require that decisions about care and treatment be made by the decisionally capable patient, following adequate discussion of the benefits, burdens and risks of the therapeutic options. When the patient is not able to participate in this process, the responsibility for making care decisions must be assumed by others. The quality of the decision-making process is directly related to • the clarity of physician-patient communications, • the patient’s understanding of the information presented, and • the patient’s trust in the physician that encourages questions and full discussion. I. Health Care Decisions and Decision Making Medicine in general and bioethics in particular deal with decisions about health care, requiring attention to patient needs and preferences in the context of medicine’s abilities. Health care, by its very nature, implicates deeply personal conceptions of life and death; the meaning of health, illness and disability; and the importance of self-image, trust and self-determination. While the patient has the greatest stake in these decisions, other parties, including care professionals, family members and administrators, bring particular perceptions and concerns to the discussion. Indeed, it is the value- and interest-based essence of health care decisions that makes them so complex, nuanced and often difficult to negotiate. II. Decision-Making Capacity In the health care setting, the exercise of autonomy is promoted or hindered by the assessment of decisional capacity, which effectively includes or excludes patients from decision making. Determining the patient’s ability to understand the discussion, consider the consequences of choice and communicate these thoughts to providers is key to supporting autonomy. Without this set of cognitive capacities, the patient will need assistance in making and articulating choices. Excluding a decisionally capable patient from making choices violates autonomy; treating an incapacitated patient “as if” she were capable makes her vulnerable to the consequences of deficient decision making. The clinical assessment of capacity is critical to deciding whether the patient can provide informed consent and refusal. A. Capacity and competence Although the terms capacity and competence are often used interchangeably, in the health care setting there are important distinctions that go beyond semantics. • Competence is a legal presumption that a person who has reached the age of majority has the requisite cognition and judgment to negotiate most legal tasks, such as entering into a contract, making a will or standing trial. • Incompetence is a functional assessment and determination by a court that, because the individual lacks this ability, she should be deprived of the opportunity to do certain things. • Because the legal system is and should be rarely involved in medical decisions, it is customary to refer to the patient’s decisional capacity, a clinical determination about the ability to make decisions about treatment or health care. B. Elements of decisional capacity A patient’s decisional capacity refers to the ability to understand and process information about diagnosis, prognosis and treatment options; weigh the relative benefits, burdens and risks of the therapeutic options; apply a set of values to the analysis; arrive at a decision that is consistent over time; and communicate the decision. Thus, decisional capacity encompasses several skills, including understanding, assessing, valuing, reasoning and articulating the factors relevant to a choice. In this way, capacity can be seen as an index of a person’s ability to exercise autonomy by making decisions that reflect personal preferences, values and judgments at a given time. This is not the same, however, as the person’s willingness to make autonomous decisions. Having capacity enables but does not obligate patients to act independently. Moreover, to insist that patients make decisions alone is to abandon them to their own autonomy. Frequently, capacitated patients will look to family, friends and trusted others to help them exercise autonomous decision making. Patients demonstrate supported autonomy when they rely on others for advice in making choices (“I want my son to help make the decision”). Some patients, especially those who are elderly or from cultures in which self-determination is not a central value, demonstrate delegated autonomy. These patients often entrust to others the authority to make decisions on their behalf (“Talk to my daughter and do whatever she thinks”). Here, autonomy is revealed in the voluntary choice to delegate rather than independently exercise decision-making authority. C. Decision-specific and fluctuating capacity Capacity is not global, but decision specific, referring to the ability to make particular decisions. A patient may have the ability to decide what to have for lunch but may be incapable of weighing the pros and cons of surgery. Because patients may have the capacity to make some decisions and not others, it is important to distinguish among the choices and facilitate the widest possible range. For example, a lower level of capacity is required to appoint a health care proxy (appreciation of the likelihood that someone will have to make decisions on his behalf and consistent designation of that person) than to make the often complex decisions the proxy will eventually make. Just as decisional capacity is not global in its application to all decisions, it is not always constant. Depending on their age, cognitive abilities, clinical condition and treatment, patients may exhibit fluctuating capacity, demonstrating greater ability to make decisions at some times than others. Elderly patients, who are especially prone to “sundowning,” often exhibit greater alertness, sharper reasoning and clearer communication earlier in the day. Recognizing this tendency allows care providers to approach patients for discussion and decisions when they are at their most capacitated, thereby increasing their opportunities for autonomous action. III. Capacity Assessment and Determination Mr. H is back again. He is a 38-year-old man who is wheelchair bound because of bilateral amputations resulting from untreated leg ulcers. Mr. H has had multiple admissions to treat his repeatedly infected sacral decubiti. Once the wounds have been debrided and the infection is under control, he signs himself out AMA to return to his fifth-floor walk-up apartment, where he has a thriving business in street drugs. He insists that, with his buddies to carry him up and down and his girlfriend to help him with meals and ADLs, he can manage just fine. He acknowledges that his recovery might be better if he remained in the hospital longer or if he came to clinic regularly but, if he is not home, his business will be picked up by other dealers. He insists that he is willing to risk future infections, although he is confident that “You guys will always get me back on my game.” Nevertheless, each time he returns, he is in worse shape and it is harder to resolve his medical problems. A. Importance of capacity determination Decisional capacity requires more than the ability to articulate choices. The obligation to respect patient autonomy and the integrity of the informed consent process depend on the patient’s ability to understand the facts and appreciate the consequences of treatment options. The presumption is that adult patients have the requisite capacity and, absent contrary evidence, decisions about treatment and nontreatment defer to patient wishes. Moreover, this deference extends to all capacitated decisions, including those that providers may think are foolish, not in the patient’s best interest or reflect poor judgment. Yet troubling decisions must be explored because any patient rejection of recommended care should be fully explored because it is likely to reflect misunderstanding and lack of trust, rather than informed and considered refusal. One useful mechanism for approaching decisional capacity is a sliding scale, which assesses the required level of capacity according to the seriousness of the decision. As the risks associated with a decision increase, the level of capacity needed to consent to or refuse the intervention should also increase. Clinically, this provides heightened scrutiny when the consequences of decisions require clinicians to be confident that patients fully appreciate the implications of their choices. The danger in the sliding scale approach is that of paternalism, the tendency to treat otherwise capable adults as though they were children in need of others to make decisions for them. In fact, we tend to only question the capacity of those who do not agree with us or who make choices that appear foolish. While it is not necessary that the family and care team agree with the patient’s decision, choices considered irrational are likely to be challenged or closely scrutinized to protect incapable patients from making decisions not in their best interest. Focusing exclusively on the content or the outcome of the decision rather than the decision-making process risks disempowering people who make risky or idiosyncratic choices. For this reason, an important safeguard is to assess the decision in terms of how it is made, evaluating the patient’s ability to manage the several skills required for capacitated decision making. Likewise, it is necessary to distinguish questioning capacity and finding incapacity. While treatment refusals or other questionable decisions may trigger a capacity assessment, they do not automatically confirm incapacity. B. Clinical standards for decisional capacity In practical terms, the following clinical standards have been suggested for assessing decision-making capacity: “The patient makes and communicates a choice. The patient appreciates the following information: • the medical situation and prognosis • the nature of recommended care • the alternative courses of care • the risks, benefits, and consequences of each alternative. Decisions are consistent with the patient’s values and goals. Decisions do not result from delusions. The patient uses reasoning to make a choice.” (Lo, Resolving Ethical Dilemmas, p. 82) C. Who assesses decisional capacity? While decisional capacity is an index of patient ability to make decisions and, therefore, implicates cognitive processes, its assessment requires more than a test of mental acuity or a psychiatric exam. The Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE), often used to evaluate cognitive ability, is useful in assessing “orientation of the subject to person, place, and time, attention span, immediate recall, short-term and long-term memory, ability to perform simple calculations, and language skills.” (Lo, 84-85) The MMSE is less helpful, however, in assessing an individual’s ability to understand, weigh alternatives and appreciate consequences—the skills required for capacitated decision making. This evaluation is more effectively done through one or more discussions that reveal the patient’s understanding of the decision’s context and implications. Likewise, while psychiatric consultation may often be helpful in assessing decisional capacity, it is neither necessary nor sufficient. Skilled psychiatric intervention can be invaluable in engaging patients in discussion, eliciting and interpreting their concerns, and identifying mental illness, cognitive impairments and interpersonal conflicts that can mask or interfere with decisional capacity. Even a skillful psychiatric consultation, however, captures only a picture of the patient’s thinking at a specific moment rather than over time. Ultimately, the clinicians who observe and interact with the patient day to day, especially residents, medical students and nursing staff, are better positioned and equipped to evaluate the quality and consistency of the patient’s decisional capacity. III. Deciding for Patients Without Capacity Frequently, health care decisions must be made for individuals who lack the capacity to make decisions for themselves. These may be individuals who were formerly but are no longer capacitated or individuals, such as newborns or the severely retarded, who never had an opportunity to form values or preferences. As a rule, both medicine and law are more comfortable providing than withholding treatment and considerable authority is customarily accorded to family, especially next of kin, in consenting to treatment. Decisions about limiting treatment are far more problematic and depend on the state in which the patient is treated. A. Background The 1976 case of Karen Ann Quinlan raised what came to be known as the “right-todie”—actually, the right to refuse treatment—and brought to national attention the risks to a patient whose treatment wishes are unknown in a high-tech, aggressive, cure-oriented health care environment. Although physicians determined that the 21-year-old was in a persistent vegetative state (PVS) and would not recover, they were reluctant to accede to her family’s wishes and discontinue life-support measures. In a unanimous landmark decision, the New Jersey Supreme Court held that if there were “no reasonable possibility” she would ever return to a “cognitive, sapient state,” her ventilator could be removed without fear of criminal or civil liability. In an analysis that weighed the interests of the state against the benefits and burdens to the patient, the court noted that the state’s interest in maintaining life “weakens and the individual’s right to privacy grows as the degree of bodily invasion increases and the prognosis dims.” The Quinlan case highlighted the potential for incapacitated patients to receive more treatment than they would have wanted. Faced with the need for substitute decision making, clinicians turned to family members, who were presumed by tradition and often law to know and act in the patients’ best interests. However, there was and remains wide variation in the decision-making authority granted by state law to surrogates, even next-of-kin. New York is one of 22 states without a surrogate decision making statute and, in the absence of a clear statement of patient wishes, strictly limits the ability of non-proxy family, even next of kin, to authorize the withholding or withdrawing of life-sustaining treatment. New York’s law, among the nation’s most restrictive, was articulated in a 1988 case. Mary O’Connor was a 77-year-old woman with profound physical and neurological impairment three years after a stroke. Her daughters refused placement of an NG tube, referring to her prior casual comments that she would not want to be maintained artificially. The court held that • care could be terminated only when “it was established by clear and convincing evidence that the patient would have so directed if he were competent and able to communicate,” and that • “the clear and convincing evidence standard requires proof . . . that the patient held a firm and settled commitment to the termination of life supports under the circumstances like those presented.” Subsequent cases, most notably the 1990 US Supreme Court case of Nancy Cruzan, sharpened the focus on determining the prior wishes of the incapacitated patient as the guide to making authentic health care decisions. When the 25-year-old woman had been in PVS for 7 years, her parents petitioned for an order to discontinue artificial nutrition and hydration. The Supreme Court, in its only such decision, recognized the protected liberty interest of a capable individual to refuse unwanted treatment, but found insufficient evidence of the prior wishes of this patient. The Court held that states may require clear and convincing evidence of a patient’s prior wishes and may insist that these decisions be based on what the individual wanted, not what others want for her. B. Standards of decision making The standards of decision making rely on the voice of the individual as the central and most authentic source. When that voice is temporarily or permanently unavailable, those who act on behalf of the patient have only indirect access to the person’s wishes and values. • • • Prior explicit articulation is the earlier expression of a capacitated person’s wishes. “What do we know about this person’s wishes based on what she has said or written?” Substituted judgment is a decision by others based on the formerly capacitated person’s inferred wishes. “Knowing what we know about this person’s behavior and prior decisions, what do we think she would want in these circumstances?” Best interest standard is used to arrive at a judgment based on what a reasonable person in this circumstance would want. This standard is used because the incapacitated person never had or did not make known treatment wishes and her preferences cannot be inferred. “What do we believe would promote this person’s well-being in these circumstances?” These standards are an attempt to get as close as possible to what would be the patient’s authentic decision, using what is known about her values and preferences or, absent that information, what a reasonable person in the same situation would be likely to choose. C. Decision making for the formerly capacitated The notion that only the explicit statement of a capable patient can inform treatment decisions has thus proved to be double edged—both a protection of the patient’s right to consent or refuse and a barrier to decision making when the patient’s wishes are unknown or inaccessible. Among the clinical setting’s greatest challenges is the patient who was formerly but is no longer capable and/or communicative, making it difficult to determine or honor her wishes. In this category are the elderly demented and patients of any age with terminal illness or irreversible injury that has impaired their decision-making ability. The medical, legal and ethical communities have responded to the formerly capacitated with two approaches—advance directives and surrogate decision making. I. Advance directives Advance directives are legal instruments intended to secure an individual’s ability to set out in advance instructions regarding health care. The 1990 federal Patient SelfDetermination Act (PSDA) requires any health care facility receiving federal funds to offer patients the opportunity to execute advance directives and assistance in doing so. Although all 50 states have statutory and/or case law governing advance directives and all states honor them, their standards differ. Two advance directives are common. The living will is a written set of instructions about the specific medical, surgical or diagnostic interventions the individual does or does not want under certain circumstances at the end of life. The structure of the document generally has a trigger, such as “If I am in an irreversible coma, . . .” or “If I am unable to recognize or relate to my loved ones and my doctors say that I will not recover, . . .” followed by the list of instructions. Because the living will presents the explicit articulation of the patient’s prior capacitated wishes, it can provide helpful guidance to family and physicians about what she would want in the current circumstances. It is limited by the fact that it is a document, a static piece of paper written when the person could not accurately anticipate her future medical condition. In addition, living wills do not always mean what they say. The person who says, “I don’t ever want to be on a respirator” probably does not mean, “I don’t want to be on a respirator for 4 hours if it gives me 10 more years on the tennis court.” What she probably means is, “I don’t want to live out the rest of my life on a respirator.” But living wills do not provide for that kind of nuance. Finally, they generally refer only to end-of-life care. Because of their limitations, living wills are most useful for someone who does not have close friends or family to make decisions in the event of incapacity. The health care proxy, sometimes called a durable power of attorney for health care decision making, is a document in which an individual legally appoints another person— an agent or proxy—to make health care decisions on her behalf after capacity has been lost. The proxy is authorized to make any and all health care decisions the individual would make, not just end-of-life decisions. The appointment presupposes a trusting relationship, familiarity with the patient’s wishes and values, and the proxy’s willingness to exercise judgment in the patient’s interest rather than rigidly following instructions. The health care proxy is recommended over the living will because it enables decision making in the event of temporary or permanent incapacity and permits greater flexibility in responding to unanticipated or rapidly changing medical conditions. This means that, although the proxy is generally required to honor the patient’s prior wishes, if those instructions do not apply to or are inconsistent with the patient’s current condition, the proxy is authorized to use her own judgment in making decisions that promote the patient’s best interest. 2. Deciding for patients without capacity or advance directives Even though people are encouraged to express their health care preferences prospectively through the designation of a health care proxy or the execution of a living will, only 1525% of the population has an advance directive. Thus, decisions for most patients who lack capacity are made by unofficial surrogates—people who assume the decisionmaking role without specific legal appointment. The people who fill this void and act on behalf of incapacitated patients include family, close friends, trusted others and, in their absence, care providers and courts, who are strangers to the patients. Health care decisions made by others are based on either substituted judgment (when the patient’s wishes can be inferred) or the best interest standard (when the patient did not have or did not articulate treatment preferences). Physicians and families of patients who are unable to participate in care discussions or decisions work to determine a course that meets clinical, legal and ethical imperatives. Goals and plans of care are considered in light of the patient’s condition and prognosis, the benefits, burdens and risks of the therapeutic options, and what is known about her wishes or best interests. When the decision is to provide treatment, families or trusted others are asked to draw on their knowledge of and concern for the patient in providing informed consent on her behalf. The more difficult decisions are those that will forego treatment, specifically lifesustaining treatment. In New York, those who care for and about incapacitated patients struggle with the requirement for clear and convincing evidence of the patient’s treatment wishes in the current clinical circumstances. While there is no precise definition of this standard, it is generally interpreted as specific statements that the patient made when capacitated that express the wish to forego particular life-sustaining interventions if she were ever in this medical condition with this prognosis. In practical terms, family members or sometimes close friends are asked to recall discussions during which the patient said something like, “If I can’t take food by mouth, I don’t ever want a feeding tube,” or “If I’m permanently unconscious or my doctors say I’m never going to get better, I don’t want to be kept alive on machines,” or “If I’m ever in a coma like Aunt Sally, I wouldn’t want to be hooked up to a respirator like she is.” Such statements presuppose prior discussions during which the patient shared her values and wishes about care, especially at the end of life. When these explicit discussions have not taken place, it is often necessary to help families recall things the patient said that may shed light on what she would have wanted in her current condition. For example, the patient may have said, “What an awful way for Aunt Sally to end her life! Being dependent on a machine like that when she’s never going to get better is the worst thing I can imagine.” While the patient may not have specifically spoken about her end-of-life care, she clearly expressed her feelings about life-sustaining interventions under certain circumstances. C. Decision making for patients who never had capacity Those who never had the opportunity or ability to form values or preferences include newborns and severely retarded adults. Addressing the needs of the endangered or profoundly disabled newborn raises the question not “What does or did this person want?,” but rather “What would this person want if she were capable of wanting anything?” Legally, the decision is almost always made by the parents who are presumed, by tradition and law, to act in the best interests of their child. However, courts tend to override parental refusals of specific life-saving interventions, especially if the child can be returned to reasonable health. Decision making for children is discussed in Chapter IV. Mentally retarded adults, like infants and young children, are considered to need decision making by others because they are and have always been incapable of reasoned judgment. As in the case of salvageable newborns, courts tend to overrule requests to withhold or terminate beneficial treatment. Because there is no way of knowing what the never-capacitated patient would have wanted and there is no history of past decision-making behavior to use as a guide, the best interest standard is invoked to inform health care decisions. In these instances, the analysis is based on the objective assessment of what would be most likely to benefit or promote the well-being of a hypothetical patient in the same circumstances. In this respect, the standard is similar to the legal reasonable person standard. In the clinical setting, the best interest standard might consider mitigation of pain and suffering, prolongation of life, restoration and enhancement of comfort, and maximizing the potential for independent functioning. To return to the case of Mrs. K, the 89-year-old patient with cellulitis of the legs: • One critical threshold question is whether, in making a decision to refuse the diagnostic work-up and return to her home, Mrs. K is exercising decisional capacity. If her decision is an informed and voluntary one, it should be honored, despite the caregivers’ concerns that it is not in her best interest. Nevertheless, efforts to persuade her to reconsider and consent to suggested treatment are still appropriate. • Disagreement with medical recommendations is not by itself evidence of a lack of decisional capacity. Mrs. K’s decision may be foolish and ill advised, but not necessarily the product of a failure of understanding. • Mrs. K has led an independent life that she attributes partly to keeping her distance from doctors. Her present decision to refuse the work-up is, therefore, consistent with a pattern of life choices that have served her relatively well. • Caregivers have an ethical and legal obligation to arrange for a safe discharge for their patients. Ethical concerns arise when capable patients make decisions that run counter to their best medical interests. Physicians have obligations to respect patient autonomy and also to promote patients’ best interests and protect them from harm. Sometimes these obligations may come into conflict. When capable patients are discharged home, especially under less-than-optimal circumstances, they should be offered appropriate nursing and other home care services. • In contrast, allowing patients who lack capacity to elect an unsafe discharge is a form of patient abandonment. Intervention by the bioethics consultation service may be helpful to resolve such cases. References Buchanan AE, Brock, DW. Deciding for Others: The Ethics of Surrogate Decision Making. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. Drane J. “Competency to Give an Informed Consent: A Model for Making Clinical Assessments,” JAMA 1984;252(7):925-927. Emanuel E, Emanuel L. “Four Models of the Physician-Patient Relationship,” JAMA 1992;267(16):2221-2226. Kennedy GL. “Legal and Ethical Issues,” in Geriatric Mental Health Care. New York: The Guilford Press, 2000, pp. 282-317. Lo B. “Assessing Decision-Making Capacity,” Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 1990;18(3):193-202. Powell T, Lowenstein B. “Refusing Life-Sustaining Treatment After Catastrophic Injury: Ethical Implications,” Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 1996;24:54-61. Schneider CE. The Practice of Autonomy: Patients, Doctors, and Medical Decisions. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.