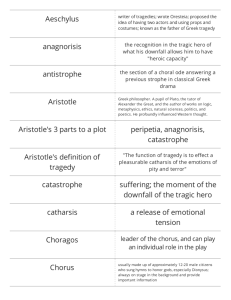

General information on tragedy and ancient Greek theater

advertisement

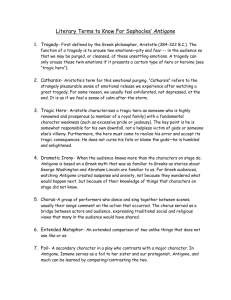

I. TRAGEDY: Tragedy depicts the downfall of a noble hero or heroine, usually through some combination of (1) hubris (complex pride), (2) fate, and the will of the gods. The tragic hero's powerful wish to achieve some goal inevitably encounters limits, usually those of (1) human frailty (flaws in reason, hubris, society), (2) the gods (through oracles, prophets, fate), (3) or nature. II. THE TRAGIC HERO The tragic hero is "a [great] man who is neither a paragon of virtue and justice nor undergoes the change to misfortune through any real badness or wickedness but because of some mistake." a) a great man: "one of those who stand in great repute and prosperity, like Oedipus and Thyestes: conspicuous men from families of that kind." The hero is neither a villain nor a model of perfection but is basically good and decent. b) "mistake" (hamartia)[*]: This Greek word, which Aristotle uses only once in the Poetics, has also been translated as "flaw" or as "error." The great man falls through--though not entirely because of--some weakness of character, some moral blindness, or error. We should note that the gods also are in some sense responsible for the hero's fall. In Poetics Aristotle speaks of HAMARTIA, sometimes literarily translated as “missing the target,” “vice” or “flaw” or “weakness” but perhaps best translated as mistake. Aristotle seems to imply that the hero is undone because of some mistake he commits, but this mistake need not be the result of a moral fault; it may be simply a miscalculation –for example, a failure to see the consequences of a deed. The hero need not die at the end, but he / she must undergo a change in fortune. In addition, the tragic hero may achieve some revelation or recognition (anagnorisis--"knowing again" or "knowing back" or "knowing throughout" ) about human fate, destiny, and the will of the gods. Aristotle quite nicely terms this sort of recognition "a change from ignorance to awareness of a bond of love or hate." TRAGIC SITUATION In Greek tragedy the tragic situation, in which the characters find themselves, is always a situation in which man seems to be deprived of all outward help and is forced to rely entirely on himself. It is a situation of extraordinary tension, of utmost conflict. Studying the plots of a number of Greek tragedies, one can find variations of two basic tragic situations: 1. First there is the case of man’s miscalculation of reality which brings about the fatal situation. 2. The second kind of tragic situation is that of man between two conflicting principles. The protagonist is suddenly put at the crossing point of two duties, both of which claim fulfillment. This is the most compelling tragic situation and is at the same time the one that has most often been chosen by the Greek dramatists. III. THREE ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS OF TRAGIC PLOT (a) "REVERSAL" (peripeteia)[*]: occurs when a situation seems to developing in one direction, then suddenly "reverses" to another. For example, when Oedipus first hears of the death of Polybus (his supposed father), the news at first seems good, but then is revealed to be disastrous. b) "RECOGNITION" (anagnorisis or "knowing again" or "knowing back" or "knowing throughout" )[*]: a change from ignorance to awareness of a bond of love or hate. For example, Oedipus kills his father in ignorance and then learns of his true relationship to the King of Thebes. Recognition scenes in tragedy are of some horrible event or secret, while those in comedy usually reunite long-lost relatives or friends. A plot with tragic reversals and recognitions best arouses pity and fear. c) "SUFFERING" (pathos)[*]: Also translated as "a calamity," the third element of plot is "a destructive or painful act." The English words "sympathy," "empathy," and "apathy" (literally, absence of suffering) all stem from this Greek word. A GLORIOUS SETTING FOR MAJESTIC DRAMA Above: Theatre at Epidaurus The theaters were outdoor auditoriums where large audiences sat upon stone benches. Starting time was daybreak. Often the citizens would sit through three tragedies, a satyr play, and a comedy. The theater was considered part of a Greek’s education, and everyone was encouraged to come. The admission charge would be refunded to playgoers who could not afford it, and they could ask to be reimbursed for the loss of a day’s wages. In Athens during drama festivals all business was suspended, the law courts were closed and prisoners were released from jail. Even women, barred from most public events, were welcomed at the theater. Greek theaters were so large that it was hard to communicate moods and feelings to distant spectators. Masks were used that instantly identified the character as young or old, man or woman, happy or sad. Further to create a larger-than-life appearance, the actor was equipped with thick-soled boots and robes with sleeves. There were other devices: masks with calm expressions on one side and angry ones on the other, allowing the actor to change moods with one swift movement of his head; funnel-shaped mouths in the masks that acted as megaphones to protect the voice. There was a rolling device that was used to simulate indoor scenes in the outdoor theater. A derrick permitted actors playing gods to arrive on the stage direct from the heavens. It was called mechanemachine-in Greek, from which came the Latin dues ex machine, or “god from the machine,” a phrase still used to mean any artificial or miraculous event introduced into a story to help solve a plot difficulty. ORIGINS OF GREEK TRAGEDY The first “tragedies” were myths called dithyrambs which were danced and sung by a “chorus” at festivals in honor of Dionysius (God of Wine and Vegetation). At first these festivals were of a “satyric” nature (gaiety, drinking, burlesque, etc). The earliest presentations probably consisted of a chorus of men dancing in a ring, reciting or chanting some Greek myth while individual performers would stand on a rough wooden platform or cart. Spectators squatted on a hillside to view these early “plays”. Eventually, the content of the dithyramb was widened to any mythological or heroic story, and an actor was introduced to answer questions posed by the choral group. (The Greek word for actor is hypokrites, which literally means "answerer." It is the source for our English word "hypocrite.") Tragedy was recognized as an official state cult in Athens in 534 BC. As time passed the sung and danced myths developed a more serious form. Instead of gaiety and burlesque the “plays” now dealt with the relationship of man and the “Gods”, and tried to illustrate some particular lesson of life. The chorus dressed in goat skins because the goat was sacred to Dionysius and goats were “prizes” which were awarded for the best plays. Therefore, the word tragedy is believed to be derived from the Greek word “tragoidia” which means “goat-song”. In the open-air, day-lit Greek theatre, the chorus was a practical necessity. It made the transitions between scenes, giving actors the chance to enter and leave the playing area, and even announced what characters those actors portrayed. But the function of the chorus goes beyond this. The choral odes, accompanied by dancing and music, were part of the entertainment itself. The chorus both commented on the events and participated in them, so that it was both involved in the action and detached from it. It was in 534 B.C. that perhaps the most important stage in the creation of drama was reached with Thespis, who invented an actor who conversed with the leader of the chorus, and by his reports of events occurring off the stage could provide the chorus with materials for fresh songs in new scenes. Through the addition of a second actor (by Aeschylus) and a third (by Sophocles), the representation was made possible of a drama which could show and develop a human situation in all its aspects. Their purpose was to ask questions about the nature of man, his position in the universe, his relation to the powers that govern his life, in short: theirs was a serious concern with the problems of man’s fate. Therefore the prime function of these dramas is the expression of the feelings and reflections excited by man’s encounters with the external forces which appear to rule his life, and the actions man takes in such an encounter. The reason for this sudden interest in man and his position in the order of the universe has been widely discussed among scholars. We have become used to speaking of the fifth century B.C. as of the “Greek Age of Enlightenment”. Civilization had developed, there were numerous changes in the fields of Greek social and political life. Along with political independence went a flowering independence of thought, a new way of thinking and of looking at the world. Philosophy was flourishing. In all fields new ideas were born, one of the most important. perhaps, being the idea of harmony as ruling principle of the cosmos. Although Greek tragedies, at first glance, seem to represent the case of individuals, what happens to these individuals could happen to other human beings just as well. The suffering protagonist is closely connected with the species Man, and shows with special distinctness what it means to be human. These Greek dramas transcend all individuality and become dramas about humanity. The real hero of Greek tragedy is humanity itself, Humanity torn between appearance and reality, pride and humility, and always at a loss when in contact with superhuman forces. It is common to all characters in a tragic situation that they are confronted with a choice. “Choice is at the heart of tragedy”. This choice may be taken (1) without much consideration, it may be taken deliberately but in ignorance of the whole truth (Oedipus) and (2) it may also be taken because it is imperative (Antigone). The point is that in all tragic circumstances a decision has either been made, or has to be made, by the character, and that the results of this decision -- whatever the choice may be -- are fatal. Act he must, but his action rests on a perilous freedom. This is what makes a Greek tragedy so awe-inspiring to watch; the inevitability with which the tragic character has to make a choice, which -- whatever it is like -- can never be the “right” choice and brings great suffering for him. One final word about tragedy; the word “tragedy” implies something intensely sad and terrible, but tragedies do not usually end upon a blackly pessimistic note. If they did, the effect upon the audience would be one of almost intolerable depression. The evil forces in a tragedy most frequently destroy the tragic hero, but the tragedy rarely ends with evil triumphant. As tragedy is probably the most revealing comment upon humanity, it seems to show us that the downfall of the human individual is perhaps inescapable. The individual inevitably has some flaw or makes some error in judgment. The hero, like any man, is human. He deviates from morality or from a full knowledge of his situation, and his deviation destroys him. Yet perhaps you remember the story of Pandora’s box which contained all the evil qualities that have since bedeviled mankind and which Pandora let loose upon the world. In the box remained one more quality to be let loose -- hope. The quality of hope is affirmative. It is necessary to morality and to a striving for a reasoned understanding of life and, therefore, necessary to tragedy. If there were no hope, there would be no consciousness of the moral and intellectual life; and if there were no such consciousness, a tragic downfall would not only be not tragic, it would also be meaningless. After every tragic action must come, at the end of the play, a reaffirmation of morality and a hope that tomorrow the world will be better. And, of course, perhaps it will. THREE FAMOUS PLAYWRIGHTS Tragic drama as we know it today is said to have been originated in the 6th century BC by the Athenian poet Aeschylus. Aeschylus included the role of a second actor, apart from the chorus. His tragedies, numbering about 90, treat such lofty themes as the nature of divinity and the relations of human beings to the gods. Only seven of his tragedies are extant, including Prometheus Bound, the story of the punishment of Prometheus, one of the Titans by the god Zeus; and the Oresteia, a trilogy portraying the murder of the Greek hero Agamemnon by his wife, her murder by their son Orestes, and Orestes’ subsequent fate. The second great Greek tragedian was Sophocles. The fine construction of his plots and the manner in which his themes and characters aroused both pity and fear led Aristotle as well as other Greek critics to consider him the greatest writer of tragedy. These qualities are found particularly in Oedipus Rex. Of the more than 100 plays that Sophocles wrote, only 7 tragedies, a satyr play (a type of comedy), and more than 1000 fragments are extant. His special contribution to tragedy was the introduction of a third actor on the stage, an innovation that was adopted later by Aeschylus. Euripides, a younger contemporary of Sophocles, was the third great Greek playwright. He wrote about 92 plays, of which 18 tragedies (one of doubtful authorship) and one complete satyr play, The Cyclops, are extant. Among his major works are Medea, about the revenge taken by the enchantress Medea on her husband Jason; and Hippolytus, about Phaedra’s love for her stepson Hippolytus and his fate after rejecting her.