Ryan J Dainty

advertisement

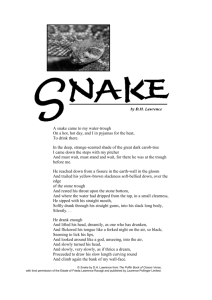

XXXX 1 XXXX X XXXXXX Professor Jacquelyn Collins English—L-202 2 June 2010 Insecurity and Self-Loathing: D.H. Lawrence, Serpents, and Gnosticism “Then the Lord God said to the serpent: ‘Because you have done this, you shall be banned from all the animals and from all the wild creatures; on your belly shall you crawl, and dirt shall you eat all the days of your life. I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and hers” (New American Bible, Gen. 3.14-15). Because of the above passage from Genesis, and others like it, the serpent, or snake, has transcended its own creatureliness and has entered the realm of the symbolic. As symbol, the snake is multivalent. It represents fear, death, deception, temptation, evil, and enmity, but perhaps its two most important symbolizations are sex and the earth. Not only is the snake a phallic symbol, but many, especially since the work of Sigmund Freud, have interpreted the serpent’s role in the “Fall of Man” as bringing about Adam and Eve’s, and by extension humankind’s, sexual awakening. A psychoanalyst would interpret God’s subsequent cursing of the serpent to the earth as an indication that sexuality is something to be repressed and even forbidden; it is an earthly desire, not a heavenly virtue. A “Gnostic” reading of this narrative throws these reflections into even higher relief, where the serpent is the hero, imparting sacred and saving knowledge to Adam and Eve—knowledge that creation is evil and that humans are, quite literally, not of this world. In reality, this knowledge is a double-edged sword. It subverts the Christian myth by creating what can be called an “I’m special” syndrome, opening the door to a type of intense, elite individualism with disastrous moral consequences. This is something that D.H. Lawrence seems to struggle with in many of his literary works. Works like The Plumed XXXX 2 Serpent, The Man Who Died and his 1923 poem, “Snake,” are a good entry point into this discussion, as they capture Lawrence’s inner struggle between “his education” and his own personal ideas and experiences that challenge this education. In these works, Lawrence uses snakes and other sexually charged symbols to explore and to ultimately forge an almost mystical religiosity with interesting moral side effects. It is helpful to more precisely define this religiosity through a discussion of Gnosticism, not as a definitive term for Lawrence’s “religion,” but rather as a grammatical framework for analysis of his work and thought.1 Gnosticism is a term used by “orthodox” Christians to describe several sectarian “Christian” groups in the first two centuries following the death (and resurrection) of Jesus of Nazareth. These groups were referred to as Gnostic (from the Greek gnosis, meaning knowledge or acquaintance) on account of the insistence that Jesus saved a select group of people by imparting to them a secret knowledge, the basis for which is a fundamental conviction that “I do not belong to this world; rather, I am divine.” From this fundamental conviction, an entire cosmological narrative is constructed that completely inverts Christian salvation history. What is of particular significance to a discussion of D.H. Lawrence centers on the “Fall of Man” narrative in Genesis, and its personal and socio-religious implications. The serpent is the hero in the story, imparting the spiritual principle to Eve (that she is divine, and eating from the fruit will give her divine knowledge, something the evil, creator 1 In the background of this paper is a biographical criticism, so it is helpful here to briefly establish the grounds on which it is safe to make inferences about Lawrence’s life from studying his work. With Lawrence, it is virtually impossible to separate his work and his life. His work is, in many ways, a “living through of his personal problems and conflicts, as well as his more general preoccupations” (Robson 298). Preeminent among his general preoccupations is the search for “a new source of vitality” (Holloway 88), a way to create and sustain passionate existence—which, for Lawrence, was “religious” in nature. Lawrence, primarily “a passionately religious man” wrote from the depths of his religious experience (90). Thus, writing, for Lawrence, is essentially an act of selfdiscovery—or better, an act of self-conquest—such that he only becomes “master in fiction through the struggle to become master of himself” (90). Given that his search for vitality and “pure passionate experience” (Robson 304) is primarily “religious” in nature, and given that this search is all over Lawrence’s written work, it is permissible to make inferences concerning Lawrence’s personal religiosity through an analysis of some of his literary texts. XXXX 3 god does not want her to possess). For Gnostics, then, the actual “Fall” predates this narrative. The “Fall” is alienation, amnesia with respect to who one is. Consequently, Christ does not come to redeem creation, but rather to redeem human beings who possess the divine spark from creation, and resurrection becomes an assent of the soul, a rising from ignorance to contemplation. The personal, social, religious, and political ramifications of this for people who were told this story and embraced it were incredible. Gnostics became an elitist and individualistic movement within the Church, alienating themselves from others on account of “being special.” Being special came, and still does come, at a cost. If one is special, he or she must prove it. Such proof, for Gnostics, usually manifested itself as either extreme asceticism (to show the individual to be not of this world) or extreme hedonism (to show that the individual is not affected by the things of this world). Thus, Gnostics developed a double-violent disrespect for the body—free will and ethical responsibility went out the window—and their behavior became indicative of extreme insecurity (always wondering whether or not one has proven his or her salvation) on the one hand, and extreme self-loathing (the product of extensive hedonism) on the other hand. D.H. Lawrence was a man familiar with insecurity and self-loathing, and he was also a man at home with such cosmological musings, “with all that is deep-rooted and elemental in the Individual and Nature, and at constant war with the mechanical and artificial, with the constraints and hypocrisies that civilization imposes” (Abrams 2314). He saw his work as an act of rediscovering “that in any individual there is a unique and inexpugnable source of vitality lying deep in the psyche” (Holloway 89) that the world with all its entrapments has suppressed. This “supreme impulse” is characteristic of Lawrence’s belief in “the dark forces of the inner self, that must not be allowed to be swamped by the rational faculties but must be brought into a XXXX 4 harmonious relation with them…[This point of view] demanded projection into art” (Abrams 2315). Lawrence can thus be depicted as a man/artist in tension, and through an analysis of his work, it is possible to trace his search for an alternative to the world, for a new vitality, and to understand the development of his thought along these lines. In the poem, “Snake,” D.H. Lawrence reflects on an encounter he had with a snake in Sicily, presenting it as an inner struggle between “the voices of his education” and the robust vitality of the snake. The snake represents, for the speaker of the poem, an alternative education, a type of secret, pure, and passionate knowledge, which Lawrence characterizes through vibrant, colorful, and poetic language in long, softly punctuated lines. As the speaker views the snake, his language invites the reader to enter “the deep, strange-scented shade of the great dark carob-tree” (Lawrence, “Snake” line 4) to “stand and wait” (6) and wonder as the snake trails “his yellowbrown slackness soft-bellied down, over the edge of the stone trough / And rest[s] his throat upon the stone bottom” (8-9). It is as if the snake invites a certain kind of waiting, of beholding, that enables the speaker to delight in his experience and in the language he uses to describe it. One way the reader experiences this delight is through the narrator’s use of alliteration: “He [the snake] sipped with his straight mouth, / Softly drank through his straight gums, into his slack long body, / Silently (11-13, italics added). By the narrator’s repetition of the s sound, the reader literally hears the snake, visualizes its movements, and appreciates its beauty. The snake receives its beauty, in part, because of its connection to the earth. The snake comes to the water trough “from a fissure in the earth-wall” (7) and is described as “earth-brown, earth-golden from the burning bowels of the earth… with Etna smoking” (20-21). Unlike the serpent in Genesis, this snake’s connection to the earth is positive, organic, and powerful. The impact of this unexpected visit on the speaker is profound. He is “honoured” that the snake XXXX 5 should seek his “hospitality from out the dark door of the earth” (38-40). Both the snake and the earth possess a secret, alluring mystique for the speaker of the poem and, by extension, for Lawrence himself. As the snake looks around “like a god” (45) and slowly withdraws “as if thrice adream” (47) into “the broken bank of my wall-face” (49), the speaker is envious: “A sort of horror, a sort of protest against his withdrawing into that horrid black hole, / Deliberately going into the blackness, and slowly drawing himself after, / Overcame me now his back was turned” (52-54). The “earth-wall,” mentioned in the beginning of the poem, has here become the “wall-face.” This is indicative of the speaker coming to see the life and vitality imbedded in the earth, and he is envious of snake, who lives in the deep recesses of that earth, possessing all the earth’s secret life and movement. This is, for Lawrence, a real, meaningful, passionate education. This, for Lawrence, is true vitality, true manhood. In the midst of this poem, this true vitality and manhood is questioned. The wonder and appreciation for the snake ceases upon the mentions of “The voice of my education” (22). At this point, the reader notes subtle changes in the poem. The tone is less playful, line length is generally shorter, and language is simpler and more sluggish, less poetic. The middle part of the poem demonstrates the narrator’s inner conflict as he wrestles with “the voices of his education” over whether or not to kill this snake: “[…] If you were a man / You would take a stick and break him now, and finish him off” (25-26). His education also forces him to challenge his experience of the beautiful, life-asserting creature: “Was it cowardice, that I dared not kill him? / Was it perversity, that I longed to talk to him” (31-32)? When the speaker finally succumbs, though half-heartedly, to the voices of his education, his feeble attempt at killing the snake is described plainly: “I looked round, I put down my pitcher, / I picked up a clumsy log / And threw it at the water-trough with a clatter” (55-57). These lines sum up the subtle changes XXXX 6 introduced in the middle part of the poem. They are short, simple, and brutish—the speaker’s actions more out of envy towards the snake and its connection to the earth than out of fidelity to the voices of his education. His cruel and nonsensical action towards the snake leaves him with “something to expiate; / A pettiness” (73-74). This is the moment of self-discovery. The sting of his missed opportunity with one of the lords of life (71-72) has, in fact, fueled his ultimate desire to embody what the snake does—the meaningful, secret, creative, and life-renewing energy of the earth. By expiating the pettiness of his education, Lawrence asserts an alternative to his education that encompasses new definitions of concepts like “manhood,” “religion,” and “sexuality.” This reading of “Snake” is, initially, a positive one. As Lawrence’s search for pure, passionate (“religious”) experience continues, however, subsequent literary works combine “manhood,” “religion,” “sexuality,” and serpent imagery in increasingly dark, negative, and even contradictory ways, which indicate a discontinuity of thought that has dangerous moral ramifications. Two such works, The Plumed Serpent (1926) and The Man Who Died (originally published as The Escaped Cock in 1929), demonstrate the deepening, darkening complexity of Lawrence’s religious search. In The Plumed Serpent, Kate, a forty-something Irish widow, is visiting Mexico city and is at once repulsed and helplessly attracted to the raw, animalistic vitality of Don Ramon and Cipriano, two political and military leaders who seek to rid Mexico of Christianity and replace it with ancient Aztec religious worship. This worship is characterized by “a reawakening of primeval sexuality marked by the dominance of the male over the female” (The Plumed Serpent v). Kate marries Cipriano, submits to his rule, “acknowledging both his phallic power and the Lawrentian notion that women should not seek sexual satisfaction as an end in itself, but find contentment in a reverent submission to the male” (v). Throughout the XXXX 7 novel, Kate teeters between this raw, sexual desire for submission and the desire to live her own life, and the moral dilemma inherent in the novel’s end is indicative of this new kind of moral complexity: “Kate was thinking to herself: What a fraud I am! I know all the time it is I who don’t altogether want them [Ramon and Cipriano]. I want myself to myself. But I can fool them so that they shan’t find out” (404). Kate desires her womanly independence. Her experience with the men has left her dramatically disillusioned, and yet she is trapped unable to leave, compelled by the phallic power and vitality the men represent. Yet, there is obvious self-deception and insecurity here on the part of Lawrence (Robson 300). Perhaps, he is as stuck as Kate.2 He cannot articulate Kate’s desire for “myself to myself” and yet have her only avenue for fulfillment be men, extrinsic to herself. The result is moral compromise, which often has disastrous side effects on the individual and on others. This moral “stuckness” is addressed in one of Lawrence’s last written works, The Man Who Died, in which Christ, awakening in the tomb on the third day, is compared to the majestic, life-filled, but tethered gamecock of a nearby peasant family. As Christ rises from death he is driven by “a dim, deep nausea of disillusion, and a resolution of which he was not even aware” (The Man Who Died 167). Once he returns to full consciousness, “the man who had died looked nakedly on life, and saw a vast resoluteness everywhere flinging itself up in stormy or subtle wave-crests, foam-tips emerging out of the blue invisible, a black and orange cock or the green flame-tongues out of the extremes of the fig-tree…these things…glowing with desire and assertion” (171). Christ sees the compulsionless vitality around him—that is, the raw assertion of nature in itself, for its own purposes—and he desires his life, a to-be solitary life, to embody this compulsionless vitality. His desire takes him abroad to Lebanon and to a temple of Isis of the 2 Biographical criticism would pick up here on the fact that Lawrence, during his writing of The Plumed Serpent, was battling a severe illness and was almost completely dependent on the care of his wife, Frieda. XXXX 8 Search, where he makes love to the priestess who believes him to be the lost Osiris. At the moment of coitus, he proclaims, “I am risen” (207). It takes Christ weeks of wandering after returning from death to finally be “rise,” to finally understand the meaning and purpose of life. He has sowed the seeds of his resurrection but must move on to others, as “the gold and flowing serpent is coiling up again” (211). These overt phallic references do not just invert, like the Gnostic myth does, but they subvert and even pervert the central mystery of the Christian narrative.3 Morality becomes individualistic and circumstantial. According to Lawrence, the moral compass is governed by the “religious” need to be “fully alive, which means not being nailed down, not reacting by convention or out of a part of oneself, but with one’s whole being, seeing the living moment as it really is in all its changing aspects” (Gomme 389). In a sense, moral compromise becomes the only functioning morality. As a type of final will and testament for Lawrence, this raises interesting moral questions not only for Lawrence himself, but also for people everywhere. Though Lawrence did not explicitly condemn creation as evil, he does make an important distinction between the elemental, intuitive aspects of the Individual and Nature and the mechanical and artificial. In this sense—as indicated by the speaker’s need to expiate a pettiness in “Snake,” by Kate’s desire for “myself to myself” in The Plumed Serpent, and by Christ’s renunciation of his first, public life, for the nihilistic, compulsionless, solitary wandering of his risen life—Lawrence can be read as one who has become disillusioned in his attempts to redeem the world, and so has settled on trying to redeem himself from the world. He ultimately succeeds, forging a neo-Gnosticism in the modern age, which finds its fulfillment in the moral compromise and sexual-mystical religiosity of many of his characters. Inherent here is Gnosticism’s elitist 3 It is important to acknowledge that Lawrence was not a Christian. He had an intensely individual spirituality that bordered on pantheism. This reference is necessary, however, insofar as Gnosticism provides a helpful grammar for an exploration of Lawrence’s work and thought. XXXX 9 individualism, which promotes a type of double-violence to the body. As a result, this sexualmystical point of view must be questioned. Too many of the problems individuals and societies have stem from this same kind of self-nihilism and disrespect for the body that Lawrence, though he would not see it this way, ultimately advocates. Yet, his work does have a certain compelling resoluteness that is hard to ignore and certainly must be appreciated. He “makes us see the complexity of many of the concrete human situations to which moral judgments are undoubtedly relevant, but which do not lend themselves to description and analysis in straightforward moral terms” (Robson 301). It must be said ultimately, however, that one needs use discretion when considering applying Lawrence’s moral judgment to any concrete human experience. XXXX 10 Works Cited Abrams, M. H. and Stephen Greenblatt, eds. “D. H. Lawrence.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature. 7th ed. Vol. 2. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2000. 23132316. Gomme, Andor. “Criticism and the Reading Public.” The Pelican Guide to English Literature: The Modern Age. 3rd ed. Vol. 7. Ed. Boris Ford. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1973. 368394. Holloway, John. “The Literary Scene.” The Pelican Guide to English Literature: The Modern Age. 3rd ed. Vol. 7. Ed. Boris Ford. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1973. 57-107. Lawrence, D.H. The Man Who Died. St. Mawr & The Man Who Died. New York: Vintage Books, 1953. 161-211. ---. The Plumed Serpent. London: Wordsworth Editions Limited, 1995. ---. “Snake.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature. 7th ed. Vol. 2. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2000. 2352-2354. The New American Bible. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. Robson, W. W. “D. H. Lawrence and Women in Love.” The Pelican Guide to English Literature: The Modern Age. 3rd ed. Vol. 7. Ed. Boris Ford. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1973. 298318.