Snake - MrDaintysClassroomandClubhouse

advertisement

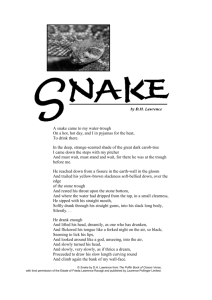

Mr. Dainty Poetry Response—“Snake” Re-learning the Snake “Then the Lord God said to the serpent: ‘Because you have done this, you shall be banned from all the animals and from all the wild creatures; on your belly shall you crawl, and dirt shall you eat all the days of your life. I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and hers” (New American Bible, Gen. 3.14-15). Because of the above passage from Genesis, and others like it, the serpent, or snake, has transcended its own creatureliness and has entered the realm of the symbolic. As symbol, the snake is multivalent. It represents fear, death, deception, temptation, evil, and enmity, but perhaps its two most important symbolizations are sex and the earth. Not only is the snake a phallic symbol, but many, especially since the work of Sigmund Freud, have interpreted the serpent’s role in the “Fall of Man” as bringing about Adam and Eve’s, and by extension humankind’s, sexual awakening. A psychoanalyst would interpret God’s subsequent cursing of the serpent to the earth as an indication that sexuality is something to be repressed and even forbidden; it is an earthly desire, not a heavenly virtue. The complicated symbol of snake parallels Lawrence’s inner struggle between “his education” and his own personal ideas and experiences that challenge this education. In the poem, “Snake,” D.H. Lawrence reflects on an encounter he had with a snake in Sicily, presenting it as an inner struggle between “the voices of his education” and the robust vitality of the snake. The snake represents, for the speaker of the poem, an alternative education, a type of secret, pure, and passionate knowledge, which Lawrence characterizes through vibrant, colorful, and poetic language in long, softly punctuated lines. As the speaker views the snake, his language invites the reader to enter “the deep, strange-scented shade of the great dark carob-tree” (Lawrence, “Snake” line 4) to “stand and wait” (6) and wonder as the snake trails “his yellowbrown slackness soft-bellied down, over the edge of the stone trough / And rest[s] his throat upon the stone bottom” (8-9). It is as if the snake invites a certain kind of waiting, of beholding, that enables the speaker to delight in his experience and in the language he uses to describe it. One way the reader experiences this delight is through the narrator’s use of alliteration: “He [the snake] sipped with his straight mouth, / Softly drank through his straight gums, into his slack long body, / Silently (11-13, italics added). By the narrator’s repetition of the s sound, the reader literally hears the snake, visualizes its movements, and appreciates its beauty. The snake receives this beauty, in part, because of its connection to the earth. The snake comes to the water trough “from a fissure in the earth-wall” (7) and is described as “earth-brown, earth-golden from the burning bowels of the earth… with Etna smoking” (20-21). Unlike the serpent in Genesis, this snake’s connection to the earth is positive, organic, and powerful. The impact of this unexpected visit on the speaker is profound. He is “honoured” that the snake should seek his “hospitality from out the dark door of the earth” (38-40). Both the snake and the earth possess a secret, alluring mystique for the speaker of the poem and, by extension, for Lawrence himself. As the snake looks around “like a god” (45) and slowly withdraws “as if thrice adream” (47) into “the broken bank of my wall-face” (49), the speaker is envious: “A sort of horror, a sort of protest against his withdrawing into that horrid black hole, / Deliberately going into the blackness, and slowly drawing himself after, / Overcame me now his back was turned” (52-54). The “earth-wall,” mentioned in the beginning of the poem, has here become the “wall-face.” This is indicative of the speaker coming to see the life and vitality imbedded in the earth, and he is envious of snake, who lives in the deep recesses of that earth, possessing all the earth’s secret life and movement. This is, for Lawrence, a real, meaningful, passionate education. This, for Lawrence, is true vitality, true manhood. In the midst of this poem, however, this true vitality and manhood is questioned. His wonder and appreciation for the snake ceases upon mentions of “The voice of my education” (22). At this point, the reader notes subtle changes in the poem. The tone is less playful, line length is generally shorter, and language is simpler and more sluggish, less poetic. The middle part of the poem demonstrates the narrator’s inner conflict as he wrestles with “the voices of his education” over whether or not to kill this snake: “[…] If you were a man / You would take a stick and break him now, and finish him off” (25-26). His education also forces him to challenge his experience of the beautiful, life-asserting creature: “Was it cowardice, that I dared not kill him? / Was it perversity, that I longed to talk to him” (31-32)? When the speaker finally succumbs, though half-heartedly, to the voices of his education, his feeble attempt at killing the snake is described plainly: “I looked round, I put down my pitcher, / I picked up a clumsy log / And threw it at the water-trough with a clatter” (55-57). These lines sum up the subtle changes introduced in the middle part of the poem. They are short, simple, and brutish—the speaker’s actions more out of envy towards the snake and its connection to the earth than out of fidelity to the voices of his education. His cruel and nonsensical action towards the snake leaves him with “something to expiate; / A pettiness” (73-74). This is the moment of self-discovery. The sting of his missed opportunity with one of the lords of life (71-72) has, in fact, fueled his ultimate desire to embody what the snake does—the meaningful, secret, creative, and life-renewing energy of the earth. By expiating the pettiness of his education, Lawrence asserts an alternative to his education that encompasses new definitions of concepts like “manhood,” “religion,” and “sexuality.”