638969476616MyersMod_LG_04

advertisement

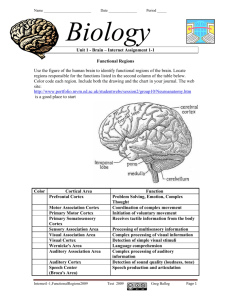

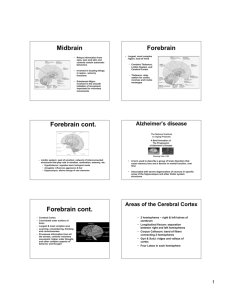

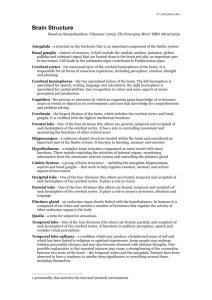

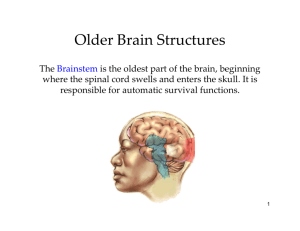

MODULE 4 PREVIEW Evolution has elaborated new brain systems on top of old. Within the brainstem are the oldest regions, the medulla and the reticular formation. The thalamus sits atop the brainstem and the cerebellum extends from the rear. The limbic system includes the amygdala, the hippocampus, and the hypothalamus. The cerebral cortex, representing the highest level of brain development, is responsible for our most complex functions. Each hemisphere of the cerebral cortex has four geographical areas: the frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal lobes. Although small, well-defined regions within these lobes control muscle movement and receive information from the body senses, most of the cortex—its association areas—are free to process other information. Experiments on split-brain patients suggest that, for most people, the left hemisphere is the more verbal and the right hemisphere excels in visual perception and the recognition of emotion. Studies of people with intact brains indicate that each hemisphere makes unique contributions to the integrated functions of the brain. GENERAL INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES 1. To describe the major techniques for studying the brain. 2. To identify the lower-level structures of the brain and discuss their respective functions. 4. To describe the complex functins of the cerebral cortex. MODULE GUIDE Lower-Level Brain Structures Lecture: Brain Puzzles, Models, and Molds Exercise A Portable Brain Model Video: Inside Information—The Brain and How It Works 1. (Close-Up) Identify and describe several techniques for studying the brain. The oldest method of studying the brain involved observing the effects of brain diseases and injuries. Powerful new techniques now reveal brain structures and activities in the living brain. By surgically lesioning and electrically stimulating specific brain areas, by recording electrical activity on the brain’s surface (EEG), and by displaying activity with computer-aided brain scans (CT, PET, MRI), neuroscientists examine the connections between brain, mind, and behavior. Film/Videos: The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat; Segment 5 and 6 of the Scientific American Frontiers series, 2nd ed. 2. Describe the functions of the brainstem, thalamus, cerebellum, and limbic system. The brainstem, the brain’s oldest and innermost region, includes the medulla, which controls heartbeat and breathing, and the reticular formation, which controls arousal. Atop the brainstem is the thalamus, the brain’s sensory switchboard. It receives information from all the senses excepts smell and sends it to the higher brain regions that deal with seeing, hearing, tasting, and touching. The cerebellum, attached to the rear of the brainstem, coordinates muscle movement. Lecture: Why Can’t We Tickle Ourselves? Exercise: Individual Differences in Physiological Functioning and Behavior Transparencies: 20 The Brainstem and Thalamus; 21 The Cerebellum Videos: Discovering Psychology: The Behaving Brain; Module 1 of The Brain series, 2nd ed.; Module 6 of The Mind series, 2nd ed. The limbic system has been linked primarily to memory, emotions, and drives. For example, one of its neural centers, the hippocampus, helps process memories for storage. Another, the amygdala, is involved in aggression and fear. A third, the hypothalamus, has been linked to various bodily maintenance functions and to pleasurable rewards. Its hormones influence the pituitary gland and thus it provides a major link between the nervous and endocrine systems. Lecture: The Case of Clive Wearing Transparency: 22 The Limbic System The Cerebral Cortex 3. Identify the four lobes of the cerebral cortex, and describe the sensory and motor functions of the cortex. The cerebral cortex is a thin sheet of cells composed of billions of nerve cells and their countless interconnections. Each of the two hemispheres of the cortex is divided into four geographic lobes (frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal). The motor cortex, at the rear of the frontal lobes, controls voluntary muscle movements. The sensory cortex, at the front of the parietal lobes, registers and processes body sensations. The occipital lobes at the back of the head receive input from the eyes. An auditory area of the temporal lobes receives information from the ears. Lecture: Einstein’s Brain and Genius Exercise: The Sensory Homunculus Project: The Human Brain Coloring Book Transparencies: 23 The Cerebral Cortex; 24 The Basic Subdivisions of the Cortex; 25 Proportion of Motor and Sensory Cortex Tissue Devoted to Each Body Part; 26 The Visual Cortex and Auditory Cortex; 27 Areas of the Cortex in Four Mammals Film/Videos: The Brain series; Modules 8 and 18 of The Mind series; Modules 7 and 25 of The Brain series, 2nd ed.; Segment 8 of the Scientific American Frontiers series, 2nd ed. 4. Discuss the importance of the association areas, and describe how damage to several different cortical areas can impair language functioning. The association areas are not involved in primary motor or sensory functions. Rather, they interpret, integrate, and act on information processed by the sensory areas. They are involved in higher mental functions, such as learning, remembering, thinking, and speaking. In general, human emotions, thoughts, and behaviors result from the intricate coordination of many brain areas. Language, for example, depends on a chain of events in several brain regions. Depending on which link in this chain is damaged, a different form of aphasia occurs. Damage to the angular gyrus leaves the person able to speak and understand but unable to read. Damage to Wernicke’s area disrupts understanding. Damage to Broca’s area disrupts speaking. Videos: Module 6 of The Brain series, 2nd ed.; Module 8 of The Mind series, 2nd ed.; Discovering Psychology: The Responsive Brain Transparencies: 28 Specialization and Integration in Language; 29 Brain Activity When Hearing, Seeing, and Speaking Words 5. Discuss the capacity of the brain to reorganize following injury or illness. Research indicates that neural tissue can reorganize in response to injury or damage. When one brain area is damaged, others may in time take over some of its function. For example, if neurons are destroyed as the result of a minor stroke, nearby neurons may partly compensate by making new connections that replace the lost ones. New evidence reveals that adult humans can also generate new brain cells. Our brains are most plastic when we are young children. In fact, children who have had an entire hemisphere removed still lead normal lives. Letures: New Brain Cells; Hemispherectomy Video: Modules 7 and 32 of The Brain series, 2nd ed.; Brain Kid and A Mind of Her Own Our Divided Brains 6. Describe research on the split brain, and discuss what it reveals regarding normal brain functioning. A split brain is one whose corpus callosum, the wide band of axon fibers that connects the two brain hemispheres, has been severed. Experiments on split-brain patients have refined our knowledge of each hemisphere’s special functions. In the laboratory, investigators ask a split-brain patient to look at a designated spot, then send information to either the left or right hemisphere (by flashing it to the right or left visual field). Quizzing each hemisphere separately, the researchers have confirmed that for most people the left hemisphere is the more verbal and the right hemisphere excels in visual perception and the recognition of emotion. Studies of people with intact brains have confirmed that the right and left hemispheres each make unique contributions to the integrated functioning of the brain. Lectures: Language on Two Sides of the Brain?; The Right Brain Movement Exercises: Behavioral Effects of the Split-Brain Operation; The Wagner Preference Inventory Project: Hemispheric Specialization PsychSim: Hemispheric Specialization Transparencies: 30 The Information Highway From Eye to Brain; 31 Testing the Divided Brain Films/Video: Segment 7 of the Scientific American Frontiers series, 2nd ed.; Module 5 of The Brain series, 2nd ed.; Mind Talk:The Brain’s New Story; Divided Brain and Consciousness; Left Brain, Right Brain 7. Discuss the relationships between brain organization, right- and left-handedness, and physical health. Approximately 95 percent of right-handers process speech primarily in the left hemisphere. Left-handers are more diverse. More than half process speech in the left hemisphere, about one-quarter in the right, and the last quarter use both hemispheres equally. The finding that the percentage of left-handers declines dramatically with age led researchers to examine the leftie’s health risks. Left-handers are more likely to have experienced birth stress, such as prematurity or the need for assisted respiration. They also endure more headaches, have more accidents, use more tobacco and alcohol, and suffer more immune system problems. However, researchers continue to debate whether left-handers have a lower life expectancy. Lecture: Left-Handedness Exercise: Handedness and Health Transparency: 32 Brain Structures