Gender and PSM - Public Management Research Association

advertisement

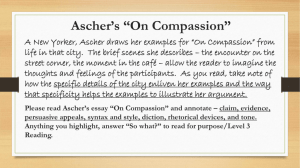

Gender Dimensions of Public Service Motivation Leisha DeHart-Davis Assistant Professor University of Kansas Justin Marlowe Assistant Professor University of Kansas Sanjay K. Pandey Assistant Professor Rutgers University, Campus at Camden Prepared for the 8th Public Management Research Conference September 29-October 1, 2005 Note: Data analyzed in this paper were collected under the auspices of the National Administrative Studies Project (NASP-II), a project supported in part by the Forum for Policy Research & Public Service at Rutgers University and under a grant from The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to the Center for State Health Policy also at Rutgers University. Naturally, this support does not necessarily imply an endorsement of analyses and opinions in the paper. 1 Gender Dimensions of Public Service Motivation Feminist scholars of public administration have lamented the dominance of masculine imagery in public administration theory and practice. In particular, expertise, virtue, leadership and bureaucracy – lauded characteristics of public administration – are based on male perspectives on the world (Ferguson 1984; Stivers 2002; Duerst-Lahti and Johnson 1990, 1992). In Ferguson’s critique of bureaucracy, public administration discourse emphasizes the control and subordination of employees by upper management, much like the control and subordination of women by men throughout history. This discourse results in the “feminization” of subordinate bureaucrats as a means of coping with their secondary status, a strategy that involves deferring to superiors, conveying favorable images to them, and aligning the subordinate’s identity with that of their superiors. From Stivers’s perspective, images of expertise, virtue and leadership are not only masculine, but deliberately un-feminine in their construction. Expertise based in science pits objectivity against emotion, masculine autonomy against feminine responsiveness, scientific authority against lay perspectives, and professional expectations against societal expectations (which for women revolve around family). Leadership is masculine not only in objective terms (more leaders are men), but in subjective terms as well (a leader should look male and pale). Public virtue is portrayed in decidedly masculine overtones, in terms of paternalistic guardians, autonomous fame seekers, commanding heroes (not heroines), and citizens historically identified as white and male. And Duerst-Lahti and Johnson suggest that public organizations may actually be more masculine than other organizational types, given the influence of the “manly” Weberian bureaucracy and its undervaluation of the culturally feminine. This paper asserts that public service motivation (PSM) is one area of public administration discourse that contains both feminine and masculine imagery. Public service motivation is defined as “an individual’s predisposition to respond to motives grounded primarily or uniquely in public and organizations” (Perry and Wise 1990). We argue that three of these motives – attraction to policymaking, compassion, and 2 commitment to the public interest – have distinct gender dimensions. Furthermore, we expect these gender dimensions to be observable in comparisons of motivation between male and female public managers. While some recent research has noted gender differences in public service motivation, these efforts have not attempted to explain the differences (Perry 1997, Moynihan and Pandey forthcoming). Given assertions in the literature that public service motivation (PSM) should increase organization effectiveness (Perry and Wise 1990, Romzek 1990, Rainey 1992), lead to higher bureaucrat performance (Perry and Wise 1990), and identify candidates for public service (Moynihan and Pandey forthcoming), it is important to scrutinize the gender dimensions of the underlying construct. After all, a purely feminine or masculine conception of PSM risks generating incomplete and biased assessments of organizations, current workers, and candidate employees. The data for examining gender dimensions of the PSM construct were collected by the National Administrative Studies Project (NASP-II). This study administered a mail survey questionnaire to managers in state health and human service agencies nationwide. Approximately half of the respondents are women. The hypotheses are tested using an ordered probit model that includes a range of demographic variables as controls. The first section profiles the public service motivation concept, with particular attention paid to Perry’s conceptual and measurement scheme. The second section, borrowing from a range of social science literature, outlines expectations for gender differences in the different forms of public service motivation. The third and fourth sections identify the data and measures used for testing these hypotheses, and the fifth section describes the results. The final two sections discuss and conclude with the broader implications of these results. Public Service Motivation Public service motivation generally relates to an individual’s desire to advance the public interest. Several authors trace the history of public service motivation as a scholarly topic, although they vary in emphasis on its intellectual precursors, including those focusing on studies conducted in the 1960s that examine differences in reward preferences between public and private sector workers (Crewson 1997, Scott and Pandey 3 2005); those emphasizing Buchanan’s 1975 comparison of job involvement between the public and private sectors or Rainey’s 1982 responding examination of more direct indicators of public service ethic (Brewer, Selden and Facer 2000; Brewer and Selden 1998); and those examining motivation scholarship in the social psychology and sociology literature from the 1960s to the 1980s (Wise 2004). Regardless of the starting point identified for public service motivation research, a turning point in this line of inquiry occurred in 1990, when Perry and Wise proposed a theoretical definition for public service motivation. The two scholars defined public service motivation as “an individual’s predisposition to respond to motives ground primarily or uniquely in public institutions and organizations”, with motive defined as a “psychological deficiency or need that an individual feels some compulsion to eliminate.” Borrowing from sociological research by Knoke and Wright-Isaac (1982), the authors delineated three categories for these motives: affective, rational, and normative. Affective motives are driven by emotion, rational motives by individual utility maximization, and norm-based motives by the desire to fulfill societal expectations (which for public service relates to the desire to serve the common good). These operational definitions clarified the public service motivation concept, which prior to that time were marked by vagueness and inconsistency of meaning (Rainey 1982). Following this research, Perry developed a measurement scale for this new operational definition of public service motivation (1996). Scale development began with the crafting of 35 survey items developed out of a literature review of and focus groups with masters of public administration students on conceptions of public service. The 35 survey items were devised to correspond to six dimensions of public service motivation: attraction to policymaking, commitment to the public interest, civic duty, social justice, compassion and self-sacrifice. With the exception of self-sacrifice, these individual motivations mapped onto the three categories of motivations identified by Perry and Wise in 1990: attraction to policymaking in the rational category, commitment to the public interest, civic duty and social justice in the norm-based category, and compassion in the affective category. (Self-sacrifice was included due to its presence in the public service literature). These survey items were included in a questionnaire administered to small 4 groups of students pursuing masters in public administration and business. Feedback from these groups triggered three revisions of survey items. The final survey items were administered in a mail questionnaire to a wide ranging sample (including MPA students, business executives, and state and county government employees) that yielded 376 responses. Confirmatory factor analysis of the resulting survey data detected four dimensions of public service motivation: attraction to policymaking, commitment to the public interest/civic duty, compassion and self sacrifice. Interestingly, Perry found that commitment to civic duty/public interest was highly correlated with self-sacrifice (suggesting that it could be combined into one dimension), but that the four-dimension model provided a better “fit” for the interdependence of the individual survey items than did the three-dimension model. The Perry PSM scale is important to public administration scholarship for several reasons. First, it represents the most methodologically sophisticated development of the public service motivation construct and is a vast improvement over previous indirect measures (Brewer Selden 1998; Brewer Selden and Facer 2000). Second, it has been used for practical purposes, including assessing attitudinal changes among President Clinton’s Americorps program participants (Perry 1996) and by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board for the 1996 Merit Principles Survey. Scholars have also used the scale to examine the relationship between PSM and individual bureaucratic performance (Alonso and Lewis 2001), individual conceptions of public service motivation (Brewer, Selden and Facer 2000), red tape perceptions (Scott and Pandey 2005), organizational effectiveness (Kim 2005), as well as the individual and organization determinants of PSM (Moynihan and Pandey, forthcoming). Given the increasing use of Perry’s PSM scale, it is important to explore its gender dimensions. We now turn to a broad array of literature that underlies expectations for gender differences in the PSM measurement scale. Public Service Motivation and Gender At the outset, the categorical drivers of public service motivation – rationality, emotion, and norms -- are themselves laden with gender connotations. Rational motives are goal oriented and assumed to be a function of individual choice based on a consideration of 5 potential gains and losses. This approach is problematic from a gender perspective given that women have historically operated within narrower physical and social boundaries than men, resulting in fewer choices to be considered and goals pursued (Kelly and Boutilier 1978). Emotion has long been considered the strength and weakness of femininity, appropriate for the perpetuation of hearth and home but an inhibition to clear thinking (Blum 1997) and an unacknowledged and undervalued skill in the marketplace (Guy and Newman 2004). As for societal norms, they differ for women and men based on the historical relegation of women to the private sphere and their corresponding exclusion from public life (Stivers 2002, Thomas 1994). We hypothesize that there will be gender dimensions to three specific public service motivations that fall within each of these categories: attraction to policymaking, a rational motive; compassion, an affective motive; and civic duty, a normative motive. Both feminist theorists (e.g. Gilligan 1982; Ruddick 1989; Mumby and Putnam 1992) and “naïve theorists”, to use Fritz Heider’s coinage for laypersons, concur that reason or rationality is typically thought of as a masculine concept and affective motives as feminine. Although there is no overwhelming support about gender dimensions of normative motives being either male or female, the concept of civic duty makes explicit reference to the public sphere and given historical limitations on women’s participation in the public sphere one would expect it to be a masculine trait. We consider these issues in greater detail below. Attraction to Policymaking Attraction to policymaking is a public service motive based on the desire to satisfy personal needs while serving the public interest (Perry and Wise 1990). Categorized as a “rational” public service motive because it involves maximizing individual utility, attraction to policymaking appeals to those who seek a sense of achievement and selfimportance (Wise 2000). Policy processes provide opportunities for both achievement and self-importance, through competition for preferred outcomes that produces winners and losers (Bardach 1977).1 1 One can make the counterargument that some public servants are not attracted to policymaking and, in fact, eschew the policy realm as an extension of the politics-administration dichotomy. 6 The game-like nature of policy processes suggest that attraction to policymaking is a masculine construct, based on studies of masculinity that indicate an emphasis on self and individuality and the pursuit of self-interest and competition (Gilligan 1982). Loden notes that boy’s sports emphasize individual accomplishment and de-emphasize team accomplishments (Loden 1985: 121). These lessons, she argues, transfer to men’s leadership styles, which are characterized by rationality, competitiveness, and the goal of winning. Lips notes that the desire to achieve does not appear to differ for males and females, but rather the motivation to achieve is aroused under different conditions by gender: men become motivated when instructions stress competition and leadership, whereas women become motivated by instructions stressing social skills (1978). Conversely, studies of feminine attributes portray struggles with establishing identity, a tendency towards collaboration over competition, and an eschewal of games with clear winners and losers in favor of win-win scenarios (Gilligan 1982, Chodrow 1974). Exemplifying the latter attribute, Kohlberg noted girls’ preferences for games involving indirect competition, such as jumprope or hopscotch (1969). Lever concluded that girls avoid conflict in game playing, favoring termination of a game when arguments broke out. By contrast, boys appealed to rules when disputes arose, resulting in short disruptions of game playing (1976). Again, Loden argues that womens leadership styles follow the patterns exhibited in children’s games, with female managers favoring cooperation and empowerment over competition and winning (1985). To illustrate how these attributes surface in a political context, Thomas notes that the influx of women into the political arena in the 1970s was expected to engender more cooperative methods of doing business than the “cutthroat competition and battles for dominance” that were the norm.” That such norms did not change led some women to withdraw from political processes altogether (Thomas 1994: 6). The historical exclusion of women from policymaking (Stivers 2000) provides another source of expectation for gender differences in attraction to policymaking. This exclusion has resulted in the continuing domination of men in politics, leading to the messages that politics is about men and for men (Elder 2004) and that women are emotionally unsuitable for politics (Fox and Lawless 2003). Thus current political processes may feel alien to potential female participants, possibly explaining the low 7 percentage of women who run for elected office or seek higher-level appointed positions (Fox and Lawless 2003, Elder 2004). While public managers are not necessarily in the thick of political competition, public organizations are not insulated from politics and performance of top management roles requires considerable political acumen. Fox and Schumann provide one of the few studies illuminating gender differences in attraction to policy processes in a public administration context (1999). In interviews with city managers, the scholars found that females and males similarly proclaimed a love of politics and commitment to a specific policy area. However, the female city managers were less likely than their male counterparts to consider themselves policy entrepreneurs; more likely than their male counterparts to see city management as oriented towards administration and not public policy formulation; and more likely than the men to say that city managers should remain neutral on controversial city issues. These observations led Fox and Schumann to conclude that women city managers are less likely to perceive themselves as policy entrepreneurs and more likely to perceive themselves as managers or facilitators than their male counterparts. Based on this evidence, we expect that: Hypothesis 1: Male public managers will be more attracted to policymaking than their female counterparts Compassion Compassion is a public service motive that entails love and concern for others and a desire that others be protected (Perry and Wise 1990). Compassion is categorized as an “affective” motive that involves responding emotionally to humankind (Frederickson and Hart 1985). It is also construed as a culturally feminine quality (Stivers 2002: 58), underscored by the tendency for women more so than men to define themselves in relation to others (Chodorow 1974) and make moral decisions based on the impacts of actions on others (Gilligan 1982). There is scholarly disagreement as to whether feminine compassion is due to nature, nurture, or a combination of both (Chodorow 1974). 8 The notion of compassion as a feminine trait is implied by historical and behavioral studies of gender differences in female and male public administrators. Women pioneered social policies and causes in the late 19th and early 20th century United States, during a time when charitable work signified the virtuous tendencies of women (Stivers 2000). The dominance of women in “caring” agencies continues to this day, supported by the overrepresentation of women in public welfare, housing, and health agencies (Lewis and Nice 1994), in employment security, human resources, and civil rights agencies (Riccucci and Sadel 1997), and also in positions that require “emotional labor,” work that requires responsiveness and a caring attitude (Guy and Newman 2004). Women are also well represented and sometimes overrepresented within federal, state and local redistributive agencies, which tend to involve caring functions (Kerr, Miller and Reid 2002, Reid, Kerr, and Miller 2000, Reid, Miller, and Kerr 2004, Newman 1995). These behavioral patterns lead us to expect that: Hypothesis 2: Female public managers will indicate a higher compassion motive than their male counterparts. It should be noted that compassion’s inclusion as a public service motive is significant given its deliberate omission from Weber’s “ideal” bureaucracy, as well as from the virtues listed by moral philosophers such as Kant and Hegel (Blum 1982).2 Compassion has also been shown to be valued equally by women and men public managers as important traits of bureaucracy (Duehrst-Lahti and Johnston 1992:144). Thus, the inclusion of compassion as a motive for public service indicates a decisive shift in how public service is conceived by scholars and practitioners alike. Commitment to Public Service A commitment to public service is based on one’s desire to fulfill a societal obligation or standard and thus is categorized as a “norm-based” motive (Perry 1997). In particular, commitment to public service entails loyalty to duty and the government and a desire to 2 According to these perspectives, compassion makes for inconsistent, unreliable and capricious decisionmaking because it departs from the universalistic in favor of the particularistic. 9 serve the public interest (Perry and Wise 1990). In 1997, Perry found that men scored higher than women on the public interest/civic duty construct, but offered no explanation as to why. Perhaps one explanation is that a norm-based public service motivation is problematic for gender when one considers that society holds significantly different expectations for women than men. These differing expectations pertain to the separation of life into the public and private spheres, the latter to which women have been relegated for most of history (Stivers 2002, Ferguson 1982, Blum 1982). Confinement to the private sphere has meant that women historically have held responsibility only towards persons with whom they have had emotional relationships; by contrast, the execution of Weberian duties and obligations requires one to execute duties independent of feelings about those duties or for whom one is performing those duties (Blum 1982). Thus, commitment to public service is construed as a masculine construct because it implies the single-minded pursuit of life in the public realm (largely male dominated) to the exclusion of life in the private realm (largely female dominated). While the argument may sound antiquated, women still bear the lion’s share of housework and childcare (Elder 2004). Further, society is ambivalent about the role of women in the public sphere. Thomas, quoting Hillary Clinton, notes “Unmarried women are considered abnormal; a married woman without children is a selfish yuppie, working women are bad mothers, and mothers who stay at home have wasted their education’ (Thomas 1994: 16). So although women have made great strides participating in both realms of life, they are less likely than men to be able to devote themselves to public life alone (Stivers 2002: 93). Accordingly, we expect that: Hypothesis 3: Public managers who are women to be less likely to indicate a commitment to public service than public managers who are men. It is important to note that we are not asserting that women are less passionate about public service, but rather that a declaration of loyalty to the public sphere will be more problematic for women, who face greater competing loyalties than men (Markus 1987: 105) 10 The Data The data for this project were collected during Phase II of the National Administrative Studies Project (NASP-II). The sampling frame comprised managers working in information-management activities at the state level in health and human service agencies. Primary human service agencies were identified according to the definition used by the American Public Human Services Association (APHSA) and include agencies housing programs related to Medicaid, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, and child welfare. Information management was broadly defined to include a range of key managerial roles such as the top program administrator, managers of information system applications, managers in charge of evaluation and research, and managers dealing with public information and communication. The sampling frame was developed with the aid of the most widely used directory of human service agency managers, namely, the 2001 APHSA directory. Application of study criteria resulted in a sampling frame of 570 managers from the fifty states and Washington, D.C. Given the small size of the sampling frame, a decision was made to administer the survey to the entire sampling frame (i.e., conduct a census). The survey-implementation process sought to minimize non-response to both the survey and specific questionnaire items. Thus the study employed Dillman’s (2000) comprehensive tailored design method approach to maximizing the response rate. This approach includes (1) a questionnaire with well-designed content; (2) the survey questionnaire formatted in accordance with the latest advances in cognitive research; (3) multiple personalized contacts, each contact including a carefully crafted message to encourage the respondent to complete the survey questionnaire; and (4) the use of real stamps on return envelopes and of features such as pre-notice letter, fax message, and phone call at key points in the survey administration, as well as use of special delivery (a combination of two-day delivery by Airborne Express and the Priority Mail service of the U.S. Postal Service). The data-collection phase of the study began in fall 2002. First, respondents were sent an alert letter informing them about the study and requesting their cooperation in completing a questionnaire to be mailed later. Approximately a week after the initial alert letter, the survey questionnaire was mailed to the respondents. The cover letter 11 accompanying the survey questionnaire outlined the study objectives, indicated the voluntary nature of the study, requested participation, and provided contact details of the project director for further informational needs and clarifications. About ten days later a combination thank you/reminder postcard was sent to all respondents, thanking those who had responded and encouraging those who had not to respond as soon as they possibly could. Nearly a month after the mailing of this postcard, a new cover letter and replacement survey were sent to nonrespondents. The cover letter emphasized the fact that it was important for everyone to respond (unless for some reason or other the respondent chose not to respond). In order to make sure that the respondents were aware of the second mailing, concomitantly with the mailing we faxed the cover letter that went with the second mailing to the nonrespondents, clearly indicating that the letter and a replacement survey were in the mail. The final step in survey administration took place about two months later when nonrespondents were sent a new cover letter and a third replacement survey with a request to complete the survey. This final mailing pointed out that this was the last opportunity for the respondents to complete the survey questionnaire and used a combination of two-day delivery by an express carrier and U.S. Postal Service Priority Mail. By the time survey administration concluded in winter 2003, a total of 274 responses were received, resulting in a 53 percent response rate. Public Service Motivation Measures Public service motivation is measured based on scales of survey items designed by Perry (1996). Three types of public service motivation serve as dependent variables: attraction to policymaking, compassion, and civic duty/public interest. Attraction to policymaking is measured as the reversed sum of a survey participant’s level of agreement with three questions, all of which take the form of a Likert-type scale ranging from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5): Politics is a dirty word The give and take of public policy making does not appeal to me. I don’t care much for politicians. 12 Cronbach’s Alpha, which measures scale reliability from “0” to “1”, is 0.72 for this scale. This Alpha score compares well with Perry’s 0.77 correlation among the same survey items (1997). Compassion is measured as the sum of a survey participant’s level of agreement with three of Perry’s eight original Likert-type items measuring compassion (1=Strongly Disagree to 5=Strongly Agree): It is difficult for me to contain my feelings when I see people in distress. I am often reminded by daily events how dependent we are on one another. I have little compassion for people in need who are unwilling to take the first step to help themselves (Reversed) Cronbach’s Alpha for this scale is 0.55, compared with that of 0.72 achieved by Perry (1997) with all eight items. Commitment to public service is measured by summing four Likert-type items from the five-item Perry scale (1=Strongly Disagree to 5=Strongly Agree): I consider public service my civic duty. Meaningful public service is very important to me. I unselfishly contribute to my community. I would prefer seeing public officials do what is best for the whole community even if it harmed my interests. Cronbach’s Alpha for the scale is 0.68, compared to the 0.69 in the Perry study (1997). The independent variable of interest is gender, coded “0” for men and “1” for women. Five control variables are included. Education represents the highest level of education completed by the survey participant and is coded “0” for Some College, “1” for a Bachelor’s Degree, or “2” for a Graduate Degree. Professionalization, adapted from Aiken and Hage (1966), ranges from 0 to 4 and is the sum of dichotomous responses (“No”=0, “Yes”=1) to the following question: 13 Are you member of a professional society (e.g. ASPA, APHSA, APHA, AMA, ANA etc.)? and statements regarding the primary Professional Societies to which the respondent belongs: I attended most meetings of the professional society in the last 2 years. I am an officeholder in the professional society. I have made presentations at recent professional society meetings. Public Sector Experience represents a respondent’s experience working in the public sector, calculated by dividing the number of years experience in the public sector by the respondent’s age. Race is categorized as “0” for White or “1” for Hispanic, Black, Asia or “Other”. Income is a categorical variable measured as “1” for earnings of less than $50,000/year; “2” for earnings between $50,000 and $75,000/year, “3” for earnings between $75,000 and $100,000/year; “4” for earnings between “$100,000 and $150,000 per year; and “5” for earnings of $150,000/year and higher. Of these control variables, women and men differ statistically only on age and income. The women in the sample average 48 years of age versus the men’s average age of 52 years. Women on average indicate earnings closer to the $50,000 to $75,000 dollar range, vs. men who indicate average earnings closer to the $75,000 to $100,000 range. (It should be noted that an ordinary least squares regression on income indicates that gender does not significantly influence income when age and education are accounted for). Model and Results The statistical method used to examine these proposed hypotheses takes into account two unique features of these data. First, we utilize ordered logistic (or “ordered logit”) regression given that the dependent variables, which are additive indices of Likert scaletype survey responses, do not meet the key ordinary least squares (OLS) regression assumption of a continuous and normally distributed dependent variable. This is because the distances between adjacent categories on each survey item included in the indices (i.e. “agree” versus “strongly agree”) may not be considered equal by every survey respondent. Ordered logit addresses this problem by assuming the dependent variable 14 follows a latent continuous, rather than an actual continuous distribution (see Long 1997, 114-147). It was also necessary to correct for possible estimation bias given that these data include responses from multiple individuals from the same state agencies. This problem was mitigated by estimating the model with a version of robust standard errors in which individual responses are allowed to cluster on their respective agencies. A series of diagnostic checks including the correlation matrix presented in Table 1, and an examination of the individual variable distributions indicate these data adhere to the ordered logit model’s basic assumptions. Efficient estimation of ordered logit also demands that the data adhere to the “parallel regression assumption,” or the claim that the independent variables have roughly the same effect on the likelihood of each dependent variable outcome. The Brandt test was not significant for any of the independent variables except gender in any of the three proposed regression models, which provides both reassurance that these data adhere to that assumption and initial support for our hypotheses. Insert Table 1 here The ordered logit regression estimates of the three proposed models are reported in Table 2. While ordered logit does not produce a fit characteristic that is directly comparable to the R-Square measure associated with traditional OLS regression, the “pseudo R-square” measures suggest these models have modest explanatory power, and that the Compassion motivation model is the best fit of the three. The p values for race and income measures suggest these variables have no statistically significant effect in any of the models, and the same p values for “organizational age” measure show it is only marginally significant in the civic duty model. Although these are necessary control variables it is clear they have no notable direct effect on individual attitudes toward these particular public service motivators. Insert Table 2 here Education and professionalism, by contrast, have notable effects on public service motivation. One of the most intuitive methods of interpreting those effects is to examine how changes in the independent variables affect the likelihood a respondent will report a higher value for the dependent variables. Those effects are presented in Table 2, which reports how an increase in each independent variable from its mean to one standard 15 deviation above its mean affects the odds a respondent will provide a higher category response for each aspect of public service motivation. Odds above 1 suggest a higher motivation score is more likely, and odds below 1 suggest stronger motivation is less likely. In the political affinity model, for example, an increase in the professionalism index from just over 1 to just over 3 increases the likelihood a respondent will report a stronger political affinity by 29%. For the compassion model that change is an even stronger 34%. By comparison, an increase in education from its average of 1.38 to its highest value of 2 results in a 9% increase in the likelihood a respondent will report a stronger political affinity. Somewhat surprisingly, that same increase in education decreases the likelihood of a stronger compassion motivation by approximately 6% (or 1 minus the reported change in odds of .94). The findings for the effects of gender generally support our hypotheses. A respondent’s gender is shown to be a significant predictor of their reported levels of both political affinity and compassion. The strongest results are for compassion, where gender is statistically significant and its coefficient suggests women are 57% more likely than men to report a higher level of compassion. These results are further explicated in Table 3, which presents a comparison, by gender, of the predicted probabilities of each compassion outcome. These probabilities were calculated by examining the ordered logit model’s predictions when each independent variable is held at its mean value and gender is assigned a value of either 0 or 1. As Table 3 shows, the general trend for compassion is that males are more likely to report lower levels of compassion where females are more likely to report higher levels of compassion. Those effects are strongest at both the “weak moderate” level, which males are 8% more likely to report, and the “strong moderate” level,” which females are 7% more likely to report. Insert Table 3 here There is also evidence of gender-based differences in attraction to politics, although those differences both contrary to our expectations and not nearly as sharp as the findings for compassion. In this case the regression coefficient suggests females are 28% more likely to report a stronger political affinity than men, although that coefficient is “marginally” significant at the .052 level. In terms predicted probabilities, females are only 3% more likely to report a “strong attraction to politics” and males are only 1-2% 16 more likely to report a weaker attraction to politics. Therefore, although these differences are statistically significant and contrary to our expectations, they are generally overshadowed by the strength of the findings in the expected direction for compassion. Discussion Various scholars have suggested that public administration discourse is dominated by male imagery, particularly in the language that defends public administration’s existence (Stivers 2002), maintains its hierarchical power relationships (Ferguson 1984) and characterizes Weberian bureaucracy (Duerst-Lahti and Johnson 1990, 1992). This study sought to explore gender dimensions in the most sophisticated measure of public service motivation, a research scale developed by Perry (1996) that is being increasingly used for practical and scholarly purposes. We expected, based upon gender studies in a variety of social science fields, to find differences by gender in how public managers respond in a survey questionnaire to three of Perry’s public service motivation dimensions: compassion, for which we expected to women to score more highly, attraction to policymaking, for which we expected men to score more highly, and commitment to the public interest/civic duty, for which we also expected higher scores from men. Ordered probit modeling supports the compassion hypothesis, but fails to support the civic duty hypothesis and contradicts the attraction to policymaking hypothesis, with women scoring more highly than men on that measure. That public managers who are women register higher compassion scores supports both stereotype and scholarship on women’s proclivities towards concern for others. But one must wonder whether the compassion result indicates that public managers who are women are really on average more compassionate than their male counterparts. Or could it be that male public managers are simply more reluctant to register such motivations given their feminine nature? As Stivers notes: “Theorists may extol the virtues of the unresponsive, caring bureaucrat who serves the public interest, but the argument will face uphill sledding until we recognize that responsiveness, caring, and service are culturally feminine qualities and that, in public administration, we are ambivalent about them for that very reason” (2002, 57-58). Despite the lack of room for compassion in public administration theory, significant outcomes in street level bureaucracy are determined by 17 the level of compassion a caseworker feels for the client (Scott and Pandey 2000; Roth 1972). Better understanding of the gender dimensions of compassion and greater acceptance of compassion can be used fruitfully to improve bureaucratic responsiveness. Regarding the civic duty dimension of PSM, perhaps the original hypothesis was antiquated in its assumption that female public managers would feel reluctant to perceive work outside the home as a central life focus and primary duty. After all, rigid sex roles are on the decline with the increase in double-income families (McGlen 2002). Beyond the division of household chores, gender norms are gradually loosening, with more traits being considered gender-neutral (Duerst-Lahti and Johnson 1992: 143). However, it was not long ago that Perry detected female respondents scoring lower on the measure than their male counterparts (1997). Additional research is needed to determine whether civic duty is a truly a gender-neutral motivation. That women scored more highly on attraction to policymaking is both surprising and intriguing, and contradicts the construal of politics as a defining feature of masculinity (Stivers 2000: 89).3 Maybe cultural norms that dictate against women’s attraction to policymaking have faded over time more rapidly than recognized. Alternatively, attraction to policymaking may resonate with women more so than men because it requires “responsiveness”, a culturally feminine quality (Stivers 2002). It should be borne in mind that our sample is drawn from redistributive agencies. While these agencies are more rule-bound than others and thus do not provide as many opportunities for policymaking (Newman 1994; Ripley and Franklin 1987), they operate in policy realms of providing health and social services, historically viewed as a female preserve. It is also possible that our results corroborate Newman’s (1994) findings based on a Florida sample: “The Florida findings support Lowi’s thesis; the most highly qualified female respondents worked in redistributive agencies, where their representation was the highest.” To sum up, given the proportionately larger number of women in these agencies and agency focus on issues of interest to women, perhaps one should expect women to assert themselves more in addressing policy issues. 3 Attraction to policymaking is a curious dimension of public service motivation given that the public administration field was launched (arguably, Svara 1998) from the assumption of a “politics-administration dichotomy” that separated the workings of elected officials from bureaucrats. And while the politicsadministration dichotomy has been long been empirically discredited, there is still evidence that professional and highly educated public servants desire to be buffered from the fickle winds of politics (). 18 At a minimum, these results suggest that the public service motivation concept devised by Perry and Wise contain gender dimensions that should be acknowledged when used by scholars and practitioners alike. But if PSM is to be used as others have suggested – including predicting candidates for public service and evaluating organization effectiveness -- much research is needed to continue this line of inquiry. For example, the results need replicating in public settings beyond state health and human service agencies and beyond managers working in information technology. Also, a fuller set of PSM measures should be used, including the self-sacrifice items and all civic duty measures, not just a subset. Conclusion What is the value of our findings on gender dimensions of the public service motivation concept? Duerst-Lahti and Johnson suggest that public organizations may actually be more masculine than other organizational types, given the influence of the “manly” Weberian bureaucracy and its undervaluation of the cultural feminine. Therefore, a conceptualization of public service motivation, encompassing both male and female dimensions, provides an opportunity to redress this imbalance. For these findings to matter, however, it is necessary to further explore and better understand the substantive importance of the public service motivation concept. There is some emerging evidence suggesting that PSM matters to the performance of organizational roles. PSM is important to organizations serving public purposes because it provides opportunities to connect individual motivation with broader organizational purposes (Moynihan and Pandey forthcoming; Perry and Wise 1990). Moreover, research about the positive effects of PSM on a variety of individual and organizational outcomes is beginning to cumulate (e.g. Brewer and Selden 1998; Crewson 1997; Scott and Pandey 2005). Despite the accumulation of evidence to this effect, our understanding of underlying mechanisms is at best in a preliminary stage. For example, Scott and Pandey (2005) note that there is little reason to believe that any given dimension of PSM has similar effects on street-level personnel who must interact with clients on a day-to-day basis and middle managers who may operate almost entirely within an organizational context. In this paper, we provide additional evidence 19 about differences between women and men on public service motivation. These differences matter to the extent that they become manifest in the work setting. Therefore, if attraction to policymaking dimension is deemed valuable for certain organizational roles, efforts to better understand the organizational and social factors that interact with gender can only help in improving individual and organizational effectiveness. Obtaining such understanding and perhaps acting on it is after all a far better alternative than letting intended or unintended gender segregation in occupations and organizations play out unhindered. Despite our “activist” inclinations, we recognize that the state of knowledge about gender dimensions of PSM is rudimentary at best. Thus, any future developments and real world application in human resource or other organizational functions, it seems wise to first focus on developing a better and more nuanced understanding of the role gender plays. We hope that such developments will be forthcoming in the near future. 20 References Alonso, Pablo, and Gregory B. Lewis. 2001. Public Service Motivation and Job Performance: Evidence From the Federal Sector. American Review of Public Administration 31 (4):363-380. Bardach, Eugene. 1977. The Implementation Game: What Happens After A Bill Becomes Law. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Blum, Lawrence. 1982. Kant's and Hegel's Moral Rationalism: A Feminist Perspective. Canadian Journal of Philosophy 12 (2):287-302. Brewer, Gene A., and Sally Coleman Selden. 1998. Whistleblowers in the Federal Civil Service: New Evidence of the Public Service Ethic. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 8 (3):413-430. Brewer, Gene A., Sally Coleman Selden, and Rex L. II Facer. 2000. Individual Conceptions of Public Service Motivation. Public Administration Review 60 (3):254-264. Buchanan, Bruce II. 1975. Red Tape and the Service Ethic. Administration & Society 6 (4):423-444. Chodorow, Nancy. 1974. Family Structure and Feminine Personality. In Woman, Culture and Society, edited by M. Z. Rosaldo and L. Lamphere. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ———. 1978. The Reproduction of Mothering. Berkeley: University of California Press. Crewson, P.E. 1997. Public Service Motivation: Building Empirical Evidence of Incidence and Effect. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 7 (4):499-519. Dillman, Don A. 2000. The Tailored Design Method. New York: J. Wiley. Duerst-Lahti, Georgia, and Cathy Marie Johnson. 1992. Management Styles, Stereotypes, and Advantages. In Women and Men of the States: Public Administrators at the State Level, edited by M. E. Guy. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. Duerst-Lahti, Georgia, and Cathy Marie Johnston. 1990. Gender and Style in Bureaucracy. Women & Politics 10 (4):67-120. Elder, Laurel. 2004. Why Women Don't Run: Explaining Women's Underrepresentation in America's Political Institutions. Women & Politics 26 (2):27-56. Ferguson, Kathy E. 1984. The Feminist Case Against Bureaucracy. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. 21 Fox, Richard L., and Jennifer L. Lawless. 2003. Family Structure, Sex-Role Socialization, and the Decision to Run for Office. Women & Politics 24 (4):19-48. Fox, Richard L., and Robert A. Schuhmann. 1999. Gender and Local Government: A Comparison of Women and Men City Managers. Public Administration Review 59 (3):231-242. Frederickson, H. George, and David K. Hart. 1985. The Public Service and the Patriotism of Benevolence. Public Administration Review 45 (5):547-553. Gilligan, Carol. 1993. In A Different Voice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Guy, Mary Ellen, and Meredith A. Newman. 2004. Women’s Jobs, Men’s Jobs: Sex Segregation and Emotional Labor. Public Administration Review 64 (3):289-298. Helgeson, Sally. 1990. The Female Advantage: Women's Ways of Leadership. New York: Doubleday Currency. Kelly, Rita Mae, and Mary Boutilier. 1978. The Making of Political Women: A Study of Socialization and Role Conflict. Chicago: Nelson-Hall. Kerr, B., W. Miller, and M. Reid. 2002. Sex-Based Occupational Segregation in U.S. State Bureaucracies: 1987-97. Public Administration Review 62 (4):412-423. Kim, Sangmook. 2004. Individual-Level Factors and Organizational Performance in Government Organizations. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 15 (2):245–261. Knoke, David, and Christine Wright-Isak. 1982. Individual Motives and Organizational Incentive Systems. Research in the Sociology of Organizations 1:209-254. Kohlberg, Lawrence. 1969. Stage and Sequence: The Cognitive-Development Approach to Socialization. In Handbook of Socialization Theory and Research, edited by D. A. Goslin. Chicago: Rand McNally. Lever, Janet. 1976. Sex Differences in the Games Children Play. Social Problems 23:478-487. Lewis, G.B., and D. Nice. 1994. Race, Sex, and Occupational Segregation in State and Local Governments. American Review of Public Administration 24:393-410. Loden, Marilyn. 1985. Feminine Leadership or How to Succeed in Business Without Being One of the Boys. New York: Times Books. Long, J. Scott. 1997. Models for Categorical and Dependent Variables, Advanced Quantitative Techniques in the Social Sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. 22 Markus, Maria. 1987. Feminism as Critique. In Feminism as Critique, edited by S. Benhabib and D. Cornell. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. McGlen, Nancy. 2002. Women, Politics, and American Society. 3rd ed. New York: Longman. Moynihan, Donald P., and Sanjay K. Pandey. Forthcoming. The Role of Organizations in Fostering Public Service Motivation. Public Administration Review. Mumby, Dennis K., and Linda L. Putnam. 1992. The Politics of Emotion: A Feminist Reading of Bounded Rationality. Academy of Management Review 17:465-486. Newman, Meredith Ann. 1994. Gender and Lowi's Thesis: Implications for Career Advancement. Public Administration Review 54 (3):277-284. Perry, James L. 1996. Measuring Public Service Motivation: An Assessment of Construct Reliability and Validity. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 6 (1):5-22. ———. 1997. Antecedents of Public Service Motivation. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 7 (2):181-197. Perry, James L., and Lois Recascino Wise. 1990. The Motivational Bases of Public Service. Public Administration Review 50:367-373. Rainey, Hal G. 1982. Reward Preferences among Public and Private Managers: In Search of the Service Ethic. American Review of Public Administration 50 (3):374-382. Reid, M. F., J. B. Kerr, and W. Miller. 2000. A Study of the Advancement of Women in Municipal Government Bureaucracies: Persistence of Glass Ceilings? Women and Politics 21 (1):35-53. Reid, M., W. Miller, and B. Kerr. 2004. Sex-Based Glass Ceilings in U.S. State-Level Bureaucracies, 1987-97. Administration & Society 36 (4):377-405. Riccucci, N. M., and J. R. Saidel. 1997. The Representativeness of State-Level Bureaucratic Leaders: A Piece of the Representative Bureaucracy Puzzle. Public Administration Review 57 (5):423-430. Ripley, Randall, and Grace Franklin. 1987. Congress, the Bureaucracy and Public Policy. Chicago: Dorsey Press. Romzek, Barbara. 1990. Employee Investment and Commitment: The Ties That Bind. Public Administration Review 50 (3):374-382. Roth, J. 1972. Some Contingencies of the Moral Evaluation and Control of Clientele: The Case of the Hospital Emergency Service. American Journal of Sociology 77 (5):839–856. 23 Ruddick, Sara. 1989. Maternal Thinking: Toward a Politics of Peace. New York: Ballantine. Scott, Patrick G., and Sanjay K. Pandey. 2005. Red Tape and Public Service Motivation: Findings from a National Survey of Managers in State Health and Human Services Agencies. Review of Public Personnel Administration 25 (2):155-180. Scott, Patrick G., and Sanjay K. Pandey. 2000. The influence of red tape on bureaucratic behavior: An experimental simulation. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 19 (4):615-633. Stivers, Camilla. 2000. Bureau Men, Settlement Women. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ———. 2002. Gender Images in Public Administration: Legitimacy and the Administrative State. 2nd. ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Svara, James. 1998. The Politics-Administration Dichotomy Model as Aberration. Public Administration Review 58 (1):51-58. Thomas, Sue. 1994. How Women Legislate. New York: Oxford University Press. Wise, Lois Recascino. 2000. The Public Service Culture. In Public Administration: Concepts and Cases, edited by R. J. Stillman. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ———. 2004. Bureaucratic Posture: On the Need for a Composite Theory of Bureaucratic Behavior. Public Administration Review 64 (6):669-680. 24 Table 1: Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations Mean SD Min. Max. 1. Political Affinity 9.66 2.74 3 15 2. Compassion 10.99 1.77 4 15 3. Civic Duty 15.38 2.56 5 20 4. Gender .47 0 1 5. Education 1.38 .68 0 2 6. Professionalism 1.18 1.41 0 4 7. Race .16 .37 0 1 8. Income 3.68 .90 1 5 9. Org. Age .30 .20 .01 .64 1 1 -.03 .20 .10 .16 .17 .02 -.05 -.10 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 .30 .18 .01 .14 .01 -.04 .04 1 -.03 .18 .23 .04 -.04 -.10 1 -.06 -.08 -.08 .07 .01 1 .21 -.19 -.03 -.05 1 -.00 -.02 .01 1 .12 -.03 1 .12 1 Table 2: Ordered Logit Estimates of Public Service Motivators Gender Education Professionalism Race Income Org. Age Wald χ2 (df, p > χ2) Political Affinity Coef. Avg. ∆ p > |z| (std. error) in Odds .453 1.28 .052 (.233) .535 1.09 .003 (.180) .184 1.29 .007 (.068) .209 1.07 .524 (.328) -.121 .90 .334 (.126) -.740 .85 .174 (.544) 24.71(6, .000) Compassion Coef. Avg.∆ (std. error) in Odds .720 1.57 (.236) .113 .94 (.210) .226 1.34 (.086) .151 1.42 (.250) -.110 .92 (.091) .398 .99 (.516) 17.66(6, .007) p > |z| .002 .589 .009 .547 .227 .441 Civic Duty Coef. Avg. ∆ (std. error) in Odds .063 1.04 (.197) .395 .76 (.197) .325 1.59 (.089) .172 1.07 (.387) -.085 .94 (.117) -1.06 .80 (.543) 27.23(6, .000) Pseudo R2 (McKelvey & Zavonia) .083 .066 .105 N 261 262 262 25 p > |z| .748 .045 .000 .657 .468 .051 Table 3: Predicted Probabilities of Public Service Motivation Outcomes by Gender Males Females Attraction to Politics Weak 14% 12% Weak Moderate 13% 12% Moderate 15% 15% Strong Moderate 9% 11% Strong 12% 15% Very Strong 6% 8% Compassion Weak 5% 2% Weak Moderate 19% 11% Moderate 19% 14% Strong Moderate 21% 21% Strong 19% 26% Very Strong 8% 13% 26