Lecture: The Election of 1912

advertisement

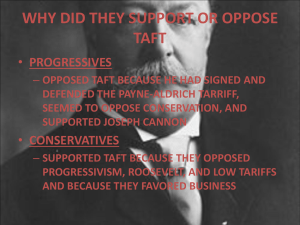

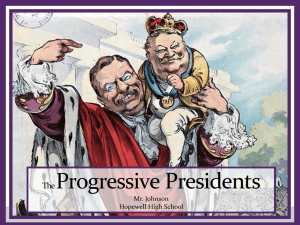

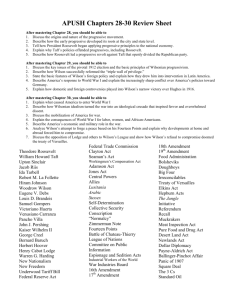

The Election of 1912 Having launched Progressive Reform at the national level, Theodore Roosevelt went on safari in Africa seeking big game. After harvesting several select specimens, he toured Europe. He missed the presidency and discovered himself suffering from the anticlimax of being such a young has-been. Still vigorous, he returned to the United States to tremendous fanfare and launched a new crusade and eventually a new third party. The story of his falling out with William Howard Taft is behind this political tantrum. The nation careened toward the showdown that was the Election of 1912, perhaps the most important presidential election in all our history. The Progressive Reform Movement had promised much, but the second decade of the 20th century asked whether the federal government could solve all the problems of an increasingly diverse society. The results of the 1912 contest revealed hope that Progressivism was up to the challenge. Incredibly, TR picked one of the most out-of-the-way places imaginable to launch his crusade. He delivered a speech in Osawatomie, Kansas, and coined the new phrase for his new Progressive program—New Nationalism. He had read Herbert Croly’s The Promise of American Life one day, and he came to believe the federal government must solve problems that even states “could not” solve for themselves. The major economic assertion of New Nationalism was that trusts were not inherently evil or harmful as long as they were subject to the federal regulation of watchdog agencies. Then he said something quite startling for an American ex-president, “Every man holds his property subject to the general right of the community to regulate its use to whatever degree the public welfare may require it.” If that quote does not immediately cause you to shudder, I wonder at which word that follows you will get a cold chill—consider the implications of your “property” being your land, your business, your inventions, or your children. In the shadows cast by the glare of TR’s popularity, the reform Governor of New Jersey began to formulate another progressive agenda he called New Freedom. Formerly a professor of political science and President of Princeton University, Woodrow Wilson was another historian and the intellectual match of Theodore Roosevelt. Wilson’s famous book was a history of politics in America, and he believed he was the one man who knew what America needed. He said all trusts were evil and should be eliminated. Furthermore, he was a Democrat born in the South (Virginia), so he embodied American political progress beyond the animosities resulting from the Civil War and Reconstruction. A brief look at the other branches of the federal government is in order before we watch the reform titans clash over the presidency. TR had created bipartisan conservatism in the Congress as the legislative branch tried to balance the power of the most powerful president the country had yet seen. Furthermore, TR had placed a Chief Justice on the Supreme Court that was a harbinger of change. The Gilded Age presidents had created a Court that was anti-labor, anti-welfare, and pro-business. That Court was so conservative that when the idea of an income tax was first raised they struck it down as unconstitutional. Roosevelt’s appointment, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., would join forces with Justice Louis Brandeis (the first Jew on the Supreme Court) to one day move the Court toward Progressivism. These two new justices admonished their fellow judges to leave laissez-faire conservative preferences out of the interpretation of laws passed by the states. They said, piously, that “law is above personal values.” They said to “Go to the Constitution,” statements that belied the fact that they were inserting their personal values and their interpretation of the Constitution just as their predecessors had. Progressives were elected to Congress and joined with the new justices in bickering with the Old Guard, the conservative Republicans left over from the days before TR transformed the presidency and launched Progressive Reform. One other candidate for the presidency in 1912 needs examination, the incumbent William Howard Taft. The reason TR eventually repudiated Taft and ran in 1912 is that his hand-picked successor had dropped his crusader legacy and more and more sided with the Old Guard. Even their personalities and temperaments were in sharp contrast. Whereas TR made speeches off the back of his presidential train as it left Washington even if the only one there to hear him was the man sweeping up after the crowd had dispersed, Taft would already be asleep in his “reinforced” berth before the train even began to move. Taft weighed around 350 lbs. throughout his adult life and did not move quickly to reform anything. He lacked TR’s personal appeal and was even more stubborn and uncompromising than Roosevelt (who always thought he was right and anyone who disagreed with him an idiot or an enemy). In a flashback to the Gilded Age, Taft’s Administration produced scandals. In the Ballinger-Pinchot Affair, Gifford Pinchot, the chief of the US Forest Service, accused Secretary of the Interior Richard Ballinger of neglect. Pinchot said Ballinger allowed unscrupulous coal mining on the 65 million acres of coal reserves TR had set aside. In an investigation Ballinger was proven innocent, but he was smeared in the Progressive press. Then he did the worst possible thing after being exonerated, he resigned in exhaustion at all the criticism. Taft was smeared because he supported Ballinger through the whole affair. Taft didn’t help his own image after having promised a lower tariff by sitting idly by while Nelson Aldrich of the Old Guard actually increased it. To the amazement of all, Taft pronounced the Payne-Aldrich tariff, “The best tariff ever passed.” A faction within the Republican Party developed because of Taft’s backsliding. TR was at the center of the formation of the Progressive Republican League, the goals of which were to either oust Taft or start a new party along the lines of New Nationalism. By 1910, TR was openly challenging Taft, his own protégé. Taft stood pat. As the Republican National Convention got under way, “Battling Bob” La Follette tried for the nomination, but TR disliked La Follette and decided to run again himself. The Old Guard, however, chose Taft, and TR and the Progressive League walked out of the convention. They fatally split the Republican Party. A rather naïve journalist asked Theodore Roosevelt if he thought he was fit to run again for the presidency. I am surprised that TR did not deck the young man, but apparently all he did was snap his teeth together and bellow, “I am as fit as a bull moose.” Again, he had coined a political slogan. The third party became known as the “Bull Moose” Progressive Party. While standing up in an open car on his way to deliver a campaign speech, TR was shot in the chest by a deranged man who had been ruined by the liquor laws TR had enforced as New York City’s Chief of Police. The impact of the bullet knocked the expresident-turned-candidate down. Then he jumped back up, spat into his hand to see if blood would come out indicating that his lung had been pierced. Amazingly, the bullet had passed through TR’s folded-up speech as well as his metal eyeglasses case that were in his inner breast pocket. Then the bullet hit a rib! Despite the outcry of his supporters, TR stood at the podium and gave his whole speech while blood slowly soaked his white shirt. He said, “I came to give a speech, and I am going to give a speech.” Even when shot in the chest he knew how to seize a political opportunity! Such histrionics did not secure him the presidency even though the Democrats were no more united at first. William Jennings Bryan, William Randolph Hearst, and Woodrow Wilson all vied for the Democratic nomination, Wilson winning on the 46th ballot at the convention! His New Freedom platform condemned Republican centralization of power, called for a lower tariff, pledged to break all trusts, and promised to destroy all privilege in government. Wilson viewed himself as the educator of the nation that would teach America what government should be. He said the US should no longer be ruled by big government and big business. The election results clearly revealed the Republicans’ self-destruction. Wilson received only 41% of the popular vote, little more than did Lincoln. TR garnered 27% while Taft won 23%. Their splitting of the Republican vote gave 435 electoral votes to Wilson, 88 to TR, and only 8 to Taft. Interestingly, the Socialist Party candidate, Eugene V. Debs, received 6% of the popular vote. Since Socialism is an even more extreme form of Progressivism, it can be said that 74% of Americans voted for a Progressive candidate in the Election of 1912 which marks its true significance. Wilson won the presidency in 1912, but Progressivism achieved a revolution in American politics that has continued with minor setbacks until our own day. This turn of events is the reason why a laissez-faire government seems so alien to us—we have never known one. Progressives came from both political parties and consolidated control over American political and economic life. One cannot say social changes were revolutionized. Wilson was foremost a Southern gentleman, and blacks did not figure into the political equation he was trying to teach America to solve. He viewed the first feature-length motion picture in America, The Birth of a Nation. The movie dramatized the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, and Wilson pronounced it a fine film. The plight of blacks was only one of the problems this crusade failed to solve.