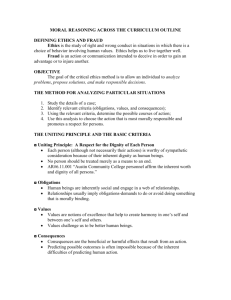

1.3 The content and function of rights

advertisement

Rights and Human Rights The UN Human Rights is arguably the most universally respected and widely discussed system of ethical principles in the world today. Few other ethical systems can aspire to the recognition and influence that Human Rights enjoy. But what, specifically, is a Human Right in the first place? What does it mean to have a moral right, and how are Human Rights defined as ethical instances of this norm? In the following I will sketch the fundamental characteristics that are a precondition for that one can interpret a given political or ethical claim as a human right. In light of the extent of this investigation, I shall limit myself to a fairly minimal definition of rights, focusing on a few uncontroversial and formal traits of rights, and the way that rights are defined in the UN declarations and conventions.1 This means that I will not discuss the more general status of Human Rights, including the question of their universal or relative status. I will assume their universal status, and review their character in so forth as this hypothesis is taken for granted. Initially, I shall emphasize five traits that characterize rights: The foundation or justification of the right, the identity of the rightsholder, the identity of the dutybearer, the content or claim of the right and finally the status of the right as absolute and XXX versus contingent. (Almond, in: Singer (ed.), 2005, p.261f)2 For each of these traits I shall endeavour to show how Human Rights are defined, and hint in which respects cultural rights distinguish themselves. As a result of this analysis I construct an analytical frame for Human Rights with three constitutive traits (preconditions) and three limitations (requirements). The understanding and conceptual clarification which I generate here will be useful in later sections when exploring the possible ways to limit duties and the problems that this occasions. 1 This means that I do not delve into attempts to establish alternative foundations for systems of rights, neither in the shape of concrete systems, e.g. the European conventions on human rights, nor the more theoretical, e.g. cosmopolitanism and discourse-ethics. 2 Note that the this does not mean that rights are defined with reference to a specific rightsholder, nor that all rights are absolute and XXX. It means only that there exists a group of parameters for rights as an ethical concept, which can be shaped differently in specific contexts. I shall limit myself to describing how the five traits that establish parameters have been defined in the UN HR. 1.1 The status of the UN Human Rights – Universal ethical system Exactly which status to attribute to the UN Human Rights, is the subject of intensive debate. The most prominent part of the discussion focuses on the issue of whether they should be considered universal or as an expression of a culturally subjective set of values, with the limited legitimacy and possible application implied thereby. Without going in depth with this debate, there are a few traits of the way that the foundation of the Human Rights is defined which it is necessary to emphasize: On the one hand the relation between the individual rights and their foundation in the inherent dignity of the human being, and on the other hand the overarching character of the system of rights as ethical, political and juridical. The most obvious interpretation of the foundation for Human Rights seems to be that they are: ”...literally, the rights that one has simply because one is a human being.” (Donnelly, 2003, p.10) But such a seemingly simple definition raises a number of questions: Why does being human equip one with rights as a moral agent? Which definition of “human being” is being employed here? And what is the connection between the distinct rights and their foundation? One can wonder why such important questions as these receive so little attention in the UN documents. The Universal Declaration on Human Rights, UDHR, argues along three different lines in the preamble: Firstly, it refers to the inherent dignity of man in a way which implies that this is a presupposition for the rights or a given. 3 Secondly, the preamble refers to the instrumental value of respecting human rights as means to liberty, justice and peace. 4 Finally, the declaration describes the rights as: ”the highest aspiration of the common people.” (UDHR, preamble) 5 In the two conventions, the foundation is somewhat more univocally defined, although not in much greater detail. In the preamble, it ”Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity […] of all members of the human family...”, UDHR, præambel. 4 This comes dangerously close to circular reasoning, because in the context of the document, the most obvious value of liberty, justice and peace is that it promotes respect for the rights described therein. Hence, in lieu of an alternative justification, Human Rights are attributed value because they promote liberty, justice and peace, and these are attributed value because the promote HR. 5 Defining the rights as an aspiration points, in ethical terms, in the direction of a consequentialist foundation, rather than a deontological one. This confusion is manifest several places in the UDHR specifically, and the UN approach to HR generally. Potentially, it could open for an interpretation of Human Rights as a type of rule-utilitarianism. In light of the constraints of this thesis however, I will limit myself to treating rights from a deontological perspective. See Kagan, 1998, p.172ff for an excellent analysis of the consequences of the implications of interpreting the rights in a consequentialist and deontological perspective, respectively. 3 is stated explicitly that: ”these rights derive from the inherent dignity of the human person”. (CCPR og CESCR, preamble)6 The explicit foundation of the UN HR thus seems to draw upon a generic concept of culture: 7 Man is defined by a common human nature, which can be realized in certain sociocultural circumstances, more specifically those that allow a human life with dignity. But this type of justification is vulnerable on two accounts: First because it relies on a generic concept of culture that refers to a universal human nature, a premise which is far from uncontroversial; second because it leaves a massive gap in the argument between the foundation of the rights and the definition and interpretation of specific rights. How does one argue convincingly that a specific right is irrevocably tied to the inherent dignity of man? For a few rights the connection will be obvious and uncontroversial, e.g. the right to life: A dignified human existence is not possible if this right is violated, simply because no human existence, dignified or otherwise, is possible without life.8 But for the vast majority of the rights covered by the UDHR and the conventions, the implicit connection to the inherent dignity of man is far less obvious. In the end, as Donnelly points out, it depends centrally on which definition of human nature one adopts. And exactly at this point of anthropology the debate is wont to shipwreck because: ”...there are few moral issues where discussion typically proves less conclusive.” (Donnelly, 2003, p.16) This vaguely defined foundation opens one avenue from which relativist critics can launch their attack, and it can appear extraordinarily difficult to justify a properly universal foundation for Human Rights as a whole. 9 However, what does remain clear is that the explicit foundation of HR is the inherent dignity of man and the universal and absolute duty not to violate this, which are then interpreted in a number of rights attributed to man as a human being. This is an essential point, because it issues a challenge to those potential rights which are not obviously and intuitively justified in virtue of the inherent dignity of man: It 6 Covenant of Civil and Political Rights and Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural rights. See appendix 1 for a chronological list of the declarations and conventions that I refer to throughout the thesis, as well as their abbrevations. Note also that the paragraph here quoted is identical in the two conventions. 7 The generic concept of culture defines man as genus. See section 3.1 8 This, of course, does not imply that the specific formulation and implementation of the right to life, or the duties that it generates among other moral agents, is either uncomplicated or uncontroversial. 9 See e.g. Donnelly, 2003, p.18ff for a discussion of the complications involved in arguing for this type of foundation, and the problems raised by the vagueness and contestability of the foundation. needs to be argued convincingly that they either protect the human dignity in a way that is not immediately obvious and intuitive, or that they are justified in terms of another foundation that is relevant in connection with Human Rights.10 If, then, we allow ourselves for the sake of argument, to ignore the foundational problems and to simply define HR as something which the individual is equipped with in virtue of a humanity which he/she shares with other human beings, it also follows that they are both universal, i.e. apply to all members of the species Homo Sapiens, and XXX, because they are tied to a trait which it is possible neither to lose nor to relinquish, the very humanity of the individual.11 Furthermore, HR are at once both descriptive and constitutive: They define the limits of a properly human existence, the dignified life, and simultaneously establish the rights that are to ensure that such an existence is possible: “Human rights shape political society, so as to shape human beings, so as to realize the possibilities of human nature, which provided the basis for these rights in the first place.” (Donnely, 2003, p.16f) 1.2 Rightsholders and dutybearers The first and most obvious trait of a right is that it is attached to a rightsholder. This means that a right presupposes a moral agent who is equipped with the right, and who can use it to raise some type of demand, in some form or other, 12 against other moral agents. The natural rightsholder in an ethical system founded on the inherent dignity of man is the individual human being. The position of Donnelly in this respect is symptomatic: in the introductory part of his defense of universal HR he constructs an analytical model of rights as an ethical concept wherein he automatically assumes that rights are attached to individuals, as rights:”one has simply because one is a human being.” (Donnelly, 2003, 10 For a concise and well-rounded discussion of the difficulties involved in using the inherent dignity of man as the ethical foundation of universal Human Rights, see: Brudholm, in: Hastrup (ed.), 2001. 11 This seems overly simplistic. First, it is of course possible to lose this trait, the most obvious way of doing so being dying. Secondly, discussions of who, exactly, possesses it are notoriously tricky, with euthanasia and abortion the two most obvious examples of moral dilemmas where the definition comes into play. 12 Almond distinguishes, as we shall see below, between ”claims”, ”powers”, ”liberties” and ”immunities” as different types of demands that a rightsholder can raise. Almond, in: Singer (ed.) 2005, s.262 p.10)13 A pertinent question, however, is whether it is also possible to ascribe rights to other kinds of entities by virtue of the inherent dignity of man? With the connection between rights and dignity left vague, there is no reason to assume that this should be an a priori impossibility; if a moral agent can potentially be offended in a way which leads directly to the violation of human dignity, then this agent will be able to claim a right on a par with those ascribed to individual human beings. Similarly, a right implies that there be one or more dutybearers, i.e. moral agents with an obligation to act upon the imperatives generated by the right endowed to the rightsholder. The most important dutybearers defined in the context of Human Rights are the states, which are under an: ”obligation [...] to promote universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and freedoms”. (CCPR and CESCR, preamble)14 But the individual is also placed under a duty, in that the conventions require individuals to assume: ”a responsibility to strive for the promotion and observance of the rights”. (CCPR og CESCR, preamble)15 Individual obligations also feature in article 29 of the UDHR, in which it is stated that: ”1. Everyone has duties to the community in which alone the free and full development of his personality is possible.” 2. In the exercise of his rights and freedoms, everyone shall be subject only to such limitation as are determined by law solely for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others and of meeting the just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare in a democratic society.” (UDHR, artikel 29) 13 Donnelly later discusses the possibility of defining communal rights, but this analysis too builds on the premise that Human Rights are fundamentally individual, an assumption which does not seem to be properly substantiated. 14 The passage is identical in the two conventions. 15 The passage is identical in the two conventions. Alternatively, one could consider the state as being under an obligation to protect the individual from violations committed by other agents. This would correspond to the second level of commitments described by Eide, what he calls the duty to respect (see below), and is also pointed out by Donnelly: ”A state that does no active harm itself is not enough. The state must also include protecting individuals against abuses by other individuals and private groups.” Donnelly, 2003, p.37. But this type of limitation must be considered a type of violation, if only a minor one. If the state can legitimately limit the rights of individuals, and is even under an obligation to do so in order to protect the rights of other individuals, then the legitimacy must rest on a justified demand of the individuals whose rights are being limited, in the shape of a their duty to respect the rights of others. That is, only by enforcing an existing duty can the limitation be understood as a limitation which does not violate the rights of individuals. The limitations in the exercise of one’s individual rights, we must assume, are ethically justifiable precisely because the individual is under an individual obligation respect the rights of other individuals. It is much harder to see what justification could be given for section one of the article, in which the duties of the individual towards the community is defined. 16 The problem of potential rightsholders is particularly relevant for the discussion of cultural rights, because cultural rights introduces cultures as moral agents with rights. I shall return to this, with a more thorough analysis of the problems that the introduction of a communal agent creates, in section 5.5. 1.3 The content and function of rights One way to distinguish between different types of rights is to divide them into four classes: ”claims”, ”liberties”, ”immunities” and ”powers”. (Almond, in: Singer (ed.), 2005, p.262) A claim allows the rightsholder to raise a demand which must be respected by the relevant dutybearer, e.g. the right to education, which allows the rightsholder demand that the state supply free access to such. (CESCR, article 13) Liberties free the rightholder from an obligation that the individual would otherwise fall under, i.e. they function as limitations of the demands that other rightsholders can raise. An example could be the rights of the child to not be held prisoner in an institution alongside adults. (CCPR, article 10, section 2 (b) and 3)17 Immunities are rights that protect the rightsholder from the actions of other agents, e.g. the right to freedom of religion. (CCPR, article 18) Finally, powers grant the rightsholder the right to perform certain actions. The right to vote and thereby grant powers to elected leaders is one of the relatively few examples of this type of right in Human Rights. (CCPR, article 25) The four classes described above illustrate the complicated nature of rights and the different roles that they can play. But it is doubtful whether it is really possible to separate and categorize universal rights along these lines. Most HR can reasonably be interpreted in ways 16 The duties of the individual to the community is in itself a controversial part of Human Rights. They seem to often generate obligations which come into conflict with or justify limitations of the individual rights. See e.g. Kjærum, in: Hastrup (ed.), 2001. 17 ”Liberties” er, som menneskerettigheder, kontroversielle, fordi deres funktion er at give rettighedshaveren et privilegium som ikke nydes af flertallet, enten i kraft af særlige omstændigheder eller i kraft af rettighedshaverens særlige karakter. ”Liberties” er således per definition anti-universelle. which lend them aspects of several of the these classes, leaving them in a grey-zone. The value of these distinctions is thus that they serve to enhance our understanding of the different ways that rights can work, rather than that they provide a tool whereby we can definitively classify and distinguish between different rights. In addition to the analysis of the rights that the rightsholder is equipped with it is important to consider the types of obligations rights generate towards the dutybearer.18 A traditional distinction in the discussion of Human Rights is the division between positive and negative rights. Negative rights generate duties not to interfere with the actions of the rightsholder in the relevant sense. A common example is the right to free speech. Positive rights, conversely, generate duties to actively intervene on behalf of the rightsholder, and include e.g. the right to education. (Source!) The division is manifest in the way that the two conventions CCPR and CESCR are constructed, with CCPR supposedly containing the negative rights and CESCR the positive. To further underline the difference, the phrasing of the obligations entailed by the two types of rights is different in the two conventions. The articles of the CCPR attribute to every human being a number of immediately and indefinitely valid rights, detailed in the individual articles. CESCR, on the other hand, merely proclaims the obligations of states to gradually realize the rights that the convention specifies, with no time limit for this goal defined. (Eide, in: Eide et al, 1995, p.22f)19 However, there are good reasons to be critical of the traditional division into positive and negative rights. Eide argues that a better distinction is to focus on the duties entailed by rights, and distinguish between three levels of commitments, all of which should apply to both conventions. The first level of commitment concerns the obligation of the state to 18 Hastrup discusses the complicated relationship between rights and duties in Human Rights in the article ”To Follow a Rule: Rights and Responsibilities revisited”. In that connection, she warns against assuming that they are isometric. One right can, in theory at least, generate several distinct duties that apply to several distinct types of agents. Consider the right to education and the different duties it generates for the state, parents and fellow citizens. In this context I shall limit myself to pointing out the necessary relationship between rights and duties, in that a right presupposes a dutybearer, just as a duty presupposes a rightsholder. By limiting the analysis to this relatively basic level, I necessarily exclude a number of interesting observations. I recommend the article for a more thorough analysis. Hastrup, in: Hastrup (ed.), 2001. 19 Also compare article two of the two conventions, which specifies the duties that apply to states in connection with the rights defined by the conventions. respect the rights of the rightsholder,20 e.g. by not practicing censorship, discrimination or imprisonment without trial. The second level concerns the obligation of the state to protect the rights of the rightsholder from violations by other agents, e.g. by maintaining a just and efficient police force, ensuring equal protection of all by the law and securing standards of safe practices in the workplace. The third level concerns the obligation of the state to promote or guarantee the rights of the rightsholder, e.g. by developing the production and distribution of food so as to meet CESCR article 11, 2. (Eide, in: Eide et al, 1995, p.36ff)21 1.4 Summing up I believe that the traits describe in the past sections can be summed up in the shape of an analytical framework for universal rights, which will apply even though we leave aside the task of filling it out with a substantial definition of rights. I suggest that a total of three constitutive and three limiting criteria apply to rights, all of which must be met for something to be properly definable as a right. 22 The constitutive traits for a universal right are: 1. The right must be attributed to a moral agent, the rightsholder, who can raise the legitimate demand defined by the right. 20 Note that although Eide assumes that the duties in question are those of the state, there is no reason why the three-tiered model can not be applied to duties in general, including duties of individuals towards other individuals. 21 Eide’s argument is developed in the context of his discussion of CESCR and is applied in the first instance to this group of rights. However, it is implied by the argument and the examples he uses that it is equally applicable in other contexts, such as those of the rights defined in the CCPR. I thus describe Eide’s method of classifying the obligations of the dutybearer without limiting it to the particular context of rights in which it was developed. Thornberry has a similar argument in: Thornberry, 1992, p.181f. 22 Baehr refers a similar list of criteria produced by a working group under the Dutch foreign ministry in connection with an analysis of communal rights: ”The advisory report contains six criteria that are considered of importance for the recognition of collective rights: (1) they must have an object which determines the substance of the right; (2) they must have a subject (bearer) who can invoke the right; (3) they must be addressed to a duty-bearer against whom they can be invoked; (4) the claim must be essential to a dignified existence; (5) the claim should not be one which can be individualized and (6) the claim must reinforce the exercise of individual human rights, and in any event should not undermine existing human rights.” Baehr, 1999, p.43f See also Donnelly, 2003, p.209ff for a nearly identical list of demands to potential communal rights. In both instances, I believe that the criteria can, with minimal modifications, apply to potential rights in general rather than communal rights specifically. a. This means that it is not possible to define a right without being able to distinguish the appropriate entity which holds the right in an uncontroversial way. 2. The right must generate a duty upon one or more moral agents to respect, protect and promote/guarantee the right, depending on the right and the context of its application. a. This means that it is not possible to define a right without a dutybearer. E.g. the right not to be exposed to natural disasters is meaningless, because although these could perhaps be said to violate human dignity, it is not possible to define a dutybearer capable of preventing these. (Almond, in: Singer, 2003, p.265)23 3. The right must be justified by an ethical principle that provides the foundation of the right in question. The function of Human Rights is to prevent violations of the inherent dignity of the human being. It is only possible to define rights whose contents are legitimized by the ethical principle in question. a. Thus there is reason to be skeptical if the right is not intuitively justified by the ethical principle at the foundation of the system of rights, and there is no convincing argument that it is necessary and justified by this principle. In addition to the above, three limiting criteria constrain the types of rights that can meaningfully be added to a system of rights. There is reason to be skeptical of defining some ethical demand as a right if: 1. The right does not address a relevant issue. One pragmatic limitation of rights in this context is that it is pointless to try to define rights to cover every conceivable situation involving the ethical principle. For practical purposes, it is necessary to focus on those rights that involve a relevant level of risk of being violated. E.g. in the context of HR, those situations in which there is a real risk that the inherent dignity of human beings will be violated.(Donnelly, 2003, p.8f)24 An important correlative to 23 In contrasts with e.g. the right to aid to the victims of such disasters which could, at least theoretically, be a right. 24 Donnelly, in this context, disthinguishes between three different ways to raise the demand defined by the right: ”assertive exercise”, ”active respect” and ”objective enjoyment”. He draws attention to the fact that the borders determining which rights it is worthwhile to define are fluid, in so far as a number of rights will this point is that this means that rights will by necessity define a minimal standard rather than the optimal standard. Or put differently, there will be situations not covered by rights, in which moral agents are free to act as they choose. 25 (consequentialism!) E.g. in the context of HR, the right fo education extends only to basic education, while states are under no requirement to offer advanced education, or to do so for free.26 2. The right addresses an issue that is already covered by an existing right (or rights). This will only needlessly complicate the system of rights, without serving the ethical principle underlying it. 3. The right conflicts with existing rights, particularly if it conflicts with a right that is better defined and more clearly justified by the ethical principle. E.g. in the context of HR, this would be the rights attributed to human agents, and among them particularly those that protect the physical freedom and well-being of the individual.27 These are formal criteria which rights must meet if they are to be considered rights in the first place. Together they constitute an analytical framework that I will employ later in the thesis to evaluate the consistency of various attempts to limit the responsibility of dutybearers for certain rights. But before then, I shall turn now to.... typically be enjoyed without being explicated. He further points out that the ultimate aim of any system of rights is to ensure that all the rights definable by the system have the status of objective enjoyment. Donnelly, 2003, p.8f. 25 This is true even if rights are interpreted as some form of rule-consequentialism, because by moving into rule-formulation the initial premise of utility-maximising has already been relaxed: There will of necessity be some situations not covered by the rules, and barring the introduction of the consequentialist principle on this level, which would take the normative system again into the realm of consequentialism proper, the individual will be free to act as it pleases in the situations ungoverned by rules. 26 Cf. CESCR article 13, section 2 (c): ”Higher education shall be made equally accessible to all, on the basis of capacity, by every appropriate means, and in particular by the progressive introduction of free education”. The contents of the article concern equal access to higher education, i.e. non-discrimination, and formulates the ambition to supply free higher education, but is in stark contrast to the clearly defined right in 2 (a): ”Primary education shall be compulsory and available free to all”. See also Donnelly, 2003, 10f. 27 Note that this is more a guiding principle than a clear-cut rule. It is possible, in principle at least, that an ethical principle can generate conflicting rights, typically by anchoring them in several rightsholders. Indeed, one of the most common ways to criticise deontological ethics is to point out its inherent difficulty in resolving the ethical dilemmas produced by such conflicting claims.