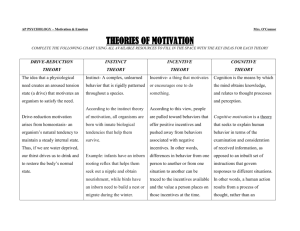

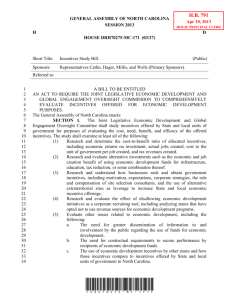

internal and external incentives

advertisement