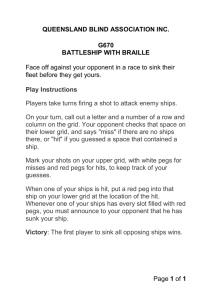

mersar

advertisement