A CRITICAL HISTORY by Lewis - Friends of the Sabbath Australia

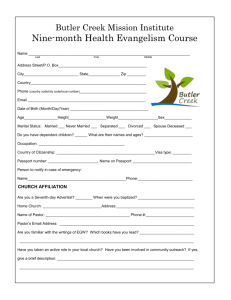

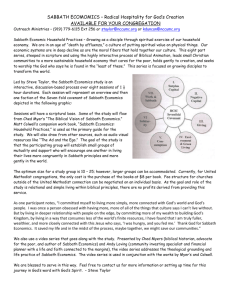

advertisement