Semiotics of Anime & Manga: Cultural Expression in Comics

advertisement

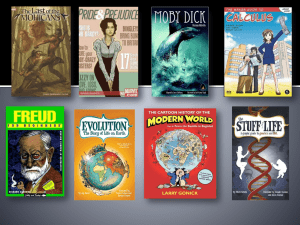

Semiotics of Anime and Manga Sydney Botts SUNY Oswego, CAS 444: Semiotics When it comes to expressing emotions and feelings, different cultures have different strategies. Some of these differences can seem strange to other cultures. However, especially in America, the forms of expression found in Japanese Anime and Manga have fascinated, and sometimes puzzled, many. The gestures and feelings are not only expressed in a different way, but the feelings that are culturally acceptable to express are also different. In this paper, we will discuss the culturally different forms of expression of Japan. Introduction Graphic novels, otherwise known as “comic books,” have been a delight to people of all ages and all cultures for hundreds, even thousands, of years. The origin of pictorial representations of stories goes back as far as ancient Egypt and the paintings of cavemen. While American comics have droves of followers all over the globe thanks to super hero genres, in more recent years, the popularity of Japanese comics (known as “Manga”) has grown to rival in popularity. Japanese manga has a completely different look and feel than American comics, due to the cultural differences between our two countries. These differences make it so that an American manga reader may not understand the denotation (or “intentional meaning”), or connotation (or “extended/symbolic meaning”), of many of the ideas being expressed, from facial expressions down to subtle familiar gestures that Americans wouldn’t normally pick up on. It is important to note that the opposite is also true. People of other cultures who would read our comics would also miss out on subtle cues that we would easily identify, possibly without even thinking. Most of the differences occur due to cultural differences in religion, language (which refers to means of communication, not specifically the spoken word), grammar (the rules by which we organize language), expressions, and what is deemed “acceptable” to the targeted reader. American culture tends to be very politically correct, and shields children from what is thought of to be “adult” subjects. However in Japan, children are exposed to these subjects at a much younger age. Because of this big cultural difference, manga can have a much heavier feel. Even some of the more cute and innocent stories will deal with very difficult issues, such as death, heartbreak, and nudity. This paper’s goal is to break down the meanings, from a semiotic (study of why things mean what they mean) perspective, of the various pictorial signs of graphic novels, focusing on manga and anime, and the differences between them and American cartoons and comics. A sign is something that stands for something else in some capacity. This can be anything from the things we call letters that make up words, to facial expressions and pictorial representations of various phenomena. Humans derive meaning from signs, in the sense that we take a conveyed or signified idea from whatever is being shown, such as tears indicating sadness, or a red light indicating “stop.” For the purposes of this paper, a culture refers to the interconnected system of meanings encoded by signs and texts, where a text is an arrangement of signs into what is sometimes called a “larger sign.” Japanese manga is a text, as are American comics, or any other country’s form ofnpictoral representation; as is language, prose, and any other subject you can think of. This paper wants to break down just what the meaning of the culture-specific signs of manga and anime are, and compare them to our familiar American culture. A Few Terms to Know Before diving into the comic book, it is important to know the difference between what properties a sign can have. All signs are a form of representation, where some “thing” has been captured and organized into a sign. Signs can be iconic, which means that the relationship it has with what it is trying to represent isn’t arbitrary; i.e. it looks like what it’s signifying. They can be indexical, which is when a sign indicates that something “exists” somewhere, such as a pointing finger. Finally, they can be symbolic, or a sign that means something conventionally, such as the eagle representing America. When it comes to comics, you are mostly dealing with iconic signs, as the story is depicted by drawings of people, places, and things. When you sit down and try to determine the meanings of the signs in graphical representation, you are participating in what is known as semiosis. You may not technically pick up a book and ask yourself “what does this mean?” but as you interpret the signs (especially in a comic book), you go through a process of deciphering each sign, as a whole or individually. Charles Pierce, a famous semiotician, described this process in three basic categories. Firstness is one’s tendency to interpret signs as simulations of the world (iconically). Secondness is relating a sign to other signs and objects in some way (indexically). Last, thirdness is learning to use signs in conventional ways (symbolically). Knowing all this, we can look at comics in a broad perspective, and then zero in on the key differences between Japanese manga and American comics. Comic Book Overview The book “Understanding Comics” by Scott McCloud is an excellent source of a general comic book interpretation. One of the key thoughts in his book that is important to understand with comics of any culture or form is the use of line, shade, background, emotion, progression of time, motion, etc. to convey the invisible. The style of these various elements of a graphic novel can vary from culture to culture and text to text, however the principles behind them are the same (McCloud). According to the semiotician Roman Jakobson, there are six possible communicative functions to expression. Each of these plays an important role in any one artist’s representation of their story. The emotive function is most important to the artist themselves; it is the intent of the addresser in communication. Basically, what are they trying to say? Many graphic novels are simply telling a story, but there are also many which try to convey certain emotions, and attempt to teach morals, or make readers aware of tragic events. The tools for this include the various uses of line, background, and contrast. If the artist’s intent is to show anger, they may include sharp lines, or flames in the background of a particular frame. The conative (effect message has on the audience) function is also closely tied to these tools, as well as referential function, which is when a message is constructed to convey information. The other three functions, when they show up, have more to do with the actual words a graphic novel will employ rather than the art, whereas the first three could go either way. Poetic function is any message delivered poetically. Phatic is when a message is used to reinforce social relations, usually a part of habit (such as a greeting). Finally, metalingual function is a message that refers to the code being used, where a code is the system in which signs are organized, and determines how those signs relate to one another and are used in communication. In any kind of narrative (story being told), these six functions help us interpret the meaning, whether we are conscious of them or not. However in the graphic novel, these functions become immersed in the drawings, rather than in the words describing the scene. Graphic novels have the opportunity, and ability, to make us see what we feel. Novels tend to follow a very structured system, whereas structuralist (the study of the usual structures in texts and signs) views can be all but lost in the graphic novel. It is because of this, especially in more recent years, that so many epic graphic novels have been able to give us a new perspective on the past, present and the future. According to Paul Gravett’s book, “Graphic Novels: Stories to Change Your Life,” the web has also opened new doors for comics. Webcomics have been able to branch out and explore “unique avenues for hyperlinks, limited animation, and multiple paths through stories” (Gravett). Graphic novels, whether on the web or in hand, open up a whole world of possibilities that regular novels can’t touch on, because while a novel can at best describe a person’s expressions and gestures, we may not get the whole picture. With graphic novels, we see the expressions, we see the movements, and we are able to decipher each element on our own, developing our own interpretations of the story. However, when we come to the split between American comics and Japanese manga, we can see that different interpretations will surface, according to the culture in which one was raised. Language, as already mentioned, is also a huge difference maker between American comics and manga. This may seem very obvious, however it is important to realize that much of the reason cultures are so different are in the ways their languages developed. Ferdinand de Saussure once suggested that language, of all sign systems, was the most complex. Humans developed language for communication, and the different ways our cultures communicate influence the way a comic strip would be written. In Japan, the language heavily revolves around an honor system, where you speak a certain way to someone you don’t know, which is completely different from someone who has authority over you, which is also different from someone you are close friends with. “Reading” Graphic Novels When you pick up a graphic novel and begin to read it, you’re taking part in more than just reading the word balloons. You not only decipher what it is the characters are saying, but you interpret their movements and body language along with their words. In a novel, if the author wanted to convey that a person was being sarcastic, they would have to describe the tone of voice in order for us to understand. However in a graphic novel, we could easily discern if someone was being sarcastic simply by the look on their face, or even the script in which the words were written. Graphic novels involve the literary code along with art, which makes them part of the interconnectedness principle, which is when different domains overlap. Just by looking at a panel in a comic, we can discern what a character is feeling, but we also gain clues from what they say. We also use various literary tools to decipher meaning, including the use of metaphor. Metaphors are when one thing is related to another something by means of connecting them somehow. In literary works, this is usually used in sayings like “Angry as a lion.” However in graphic novels, metaphors can be made visual; rather than someone being described as lion-like in their anger, an artist could draw the character with a mane, or sharp teeth. Similar to this is the use of metonymy, which is when related objects are used to refer to one another. Because of the comic’s ability to show us what’s going on, not just tell us, it also becomes easier to recognize some of the subtexts involved. Hidden meanings behind the text can be more obvious when “reading between the lines” means looking at what the drawing is depicting on the page. It is also very useful to see how a text changes over time (diachronically). Stories have a natural ebb and flow, and in the graphic novel, one will be able to literally see if a story is becoming darker, or more ridiculous as the panels go on by the way the lines and shapes begin to change. Also, the synchronic (present) meaning of the text is visually expressed. The differences between American comics and Japanese comics make the idea that language, culture, and thought are bonded together seem very evident. This idea is known as the Whorfian Hypothesis, named for Benjamin Lee Whorf. The differences in our cultures spurned very different means of expression and interpretation. Martin Goodman’s article in the online magazine “Animation World,” states “1) Animation is a specific form of communication arts that 2) Is inseparable from the culture that produces and consumes it” (Goodman). American Comics Most people, when they think of comic books, automatically picture the likes of Superman, Batman, and Spiderman in their minds. American comics are almost completely overshadowed by the super-hero genre. The popularity of these comic books have given inspiration in recent years for movie makers to systematically go through and cinematize many of the most popular American super heroes. Most of our stories are centered around the super hero myths (a story which attempts to explain some part of life through super-human or god-like characters) due to the nature of our society. According to semiotician Claude Levi-Strauss, myth plays a key role in narratives, as they showcase the various oppositions built into meanings. Typical of super-hero stories is the contrast between good and evil, right and wrong, light and dark, etc.. Saussure also pointed out that signs only have meaning in differential relation to other signs. How does one know what is good, without understanding what is bad? Especially in recent years the lines between good and evil in comic books begin to blur, and sometimes may even overlap, with a hero having to do something “wrong” in order to make something “right.” Americans are always striving to do things better and faster. To do the “right” things as opposed to the wrong. We are strongly tied to our beliefs in freedom, and when we come across something that attempts to do wrong, or take away that freedom, there is a need for a hero to emerge. Many of the super-hero stories have taken darker turns over the years, and pushed the envelope of just how far one will go to do what is “right.” Many American comics have taken a very post-modern viewpoint, which is the belief that the here and now is all that matters. This view is evident in comics which feature the “anti-hero.” This type of character typically will act in a way that is best for them; if they feel it is in their interest to save a life, they will do so, however they can walk a very dark line as well. In “The Quest for Meaning” by Marcel Danesi, he writes that “lines, points, and shapes are the basic visual signifiers that we use to assemble visual texts. Other visual signifiers include value, color, and texture” (Danesi). American comics are characterized by strong, defined lines, and vivid colors, with a wide range in values. By using these key elements of visual text, American comics are able to convey a wide range of looks and feels, from the already mentioned super hero genre, full of loud colors, and sometimes dark values, to the moralistic and comical genres, with softer colors and simple lines. However, it is still important to note that comics in general are still looked at as a young boy’s reading in American standards, not something for adult minds. While in more recent years, many heavier stories aimed at a more mature audience have surfaced, the vast majority of the American comic book market is teenage boys. This is drastically different from Japan, where manga is popular with almost any age group for both genders. How is Japan Different? As already mentioned, Japanese children are exposed to what Americans think of as “adult” concepts at a much younger age than Americans are used to. Blood and gore, swearing, death, destruction, and many other heavy concepts are not shielded from young minds as it is in our culture. Because of this, manga and anime has a very, very wide range of subject matter, from the afore mentioned “heavy” concepts, to “bubble-gum” stories, and everywhere in between. But while differences in Japan’s subject range are important, the true differences between American comics and manga lie in the codes in which they are written, which are culturally different. In Japan, there is an entirely different code of respect and honor. Much of this is reflected in the Japanese language in its variety of what is called “honorifics,” which is placed at the end of one’s name, and depends on the relationship of the person who is referring to them. A person who is talking to an acquaintance, or a superior (someone not a close friend), they would use “-san” when speaking about them. Younger people when speaking to close friends would use “-chan,” and so on. In America these respect lines are blurred. While we do have the common “Mr., Mrs., etc.” titles, they are our only honorifics, and there is no variety for certain cases. Americans have gotten used to a familiar social system where respect is not thought of automatically. While the honorifics are purely a language code difference, there are other codes which Japan and America differ on drastically. Micheal Mosley’s “A Semiotic Analysis of Anime” says: “A reading of sign systems is organized by recognizing that signification, or the relationship between signifier and signified, occurs along two axes of meaning; paradigmatic and syntagmatic. At a paradigmatic level, one must consider the metaphoric implication of the entire set of signs from which the one used is chosen. At the syntagmatic, the message into which the chosen signs are combined is subject to examination. The cybernetic world of Anime brings forth a convoluted morass of semiotic representations. Signifiers and signifieds disconnect and reconnect; simultaneously rejecting and supporting dominant ideology” (Mosley). Japanese anime and manga tends to confuse the American reader due to the sometimes zany antics of the characters in the story. One must keep the context in mind. A context is the environment (both physical and social) in which signs are produced and interpreted. Therefore, we cannot simply write off a sign or gesture which we don’t recognize without discovering the cultural meaning behind it. The Meanings in Manga and Anime As in any kind of visual storytelling, both American and Japanese comics have a certain style they adhere to. Some of these styles can overlap across the cultures, by influence (intertextually) or coincidence. However much of the manga style itself is the key features that make it so different from other visual representations. Emotions are expressed differently. Line and background has a different feel. Facial expressions are different. Even the use of scenic panels versus character panels is different. In Carey Goldberg of the Boston Globe’s article, “To use a camera analogy, ‘the Americans are more zoom and the East Asians are more panoramic,’ said Dr. Denise Park of the Center for Brain Health at the University of Texas in Dallas. ‘The Easterner probably sees more, and the Westerner probably sees less, but in more detail’” (Goldberg). Marc Hairston’s essay in the book “Mechademia” picks a perfect example of this use of scenic panels versus dialogue heavy panel-by-panel storytelling. He describes the “mono no aware (‘sensitivity to things’), the classic Japanese aesthetic sense of melancholy and an acceptance of beauty inherent in the impermanence of things” (Lunning, 256). A contrary instance of this is pointed out in Neil Cohn’s Essay, “Cross-culture Space.” He points out observations that had been made between American and Japanese children’s drawings. The observations made were that Japanese children tend to draw more “zoomed in” pictures than other viewpoints. He states “Given that both American and Japanese children are exposed to the same visual culture in video games and television, she attributes these differences to the pervasive role that manga plays in Japanese culture in comparison to American children’s readings of comic books” (Cohn) However, Cohn’s website points out that this tendency to “zoom in” on elements of a scene doesn’t necessarily mean that they aren’t focusing on the whole. It is possible that the Japanese tendency is to recognize the whole by focusing on the parts. By analyzing each of the elements of a scene, a panoramic view can be taken. Facial Expressions When it comes to physical cues from human to human, we recognize what are called gestures, or representation by the hands and arms (sometimes head), that indicate certain feelings or emotions. Also, a gesticulant is any movement of the hands that comes naturally during speech. A thumbs up or thumbs down to when telling that something is good or bad is an example. These gestures and gesticulants tie in heavily to language use, and also reaffirm the honor code in Japan, where bowing to one’s superiors is considered highly important. Sometimes even a subtle bow of the head while talking to someone who has authority over someone else is often seen. In Japan, the gestures and facial expressions used would catch most American readers offguard. Take the following picture for example: Picture from http://www.emaki.net/essays/japanese_vl.pdf Some of these expressions Americans would still recognize, such as Anger, or Relief (albeit they may not be familiar with the puff of air coming from the mouth, most Americans would recognize this as a visual representation of the breath one usually exhales when relieved). However many would not understand the nosebleed for Lust, or the droplet for shock, or the other signs here. The cultural differences here are plain. Americans aren’t familiar with the old wives tale that if a boy stares at a beautiful woman for too long, that their nose will bleed. This is a perfect example of a difference of context. Since Americans are not in the same context that the Japanese are, many of these usual forms of expression fly right past us as odd or awkward. However if a Japanese person were to see a boy with hairy palms in an American comic, the opposite would happen. Almost every American understands what such a depiction implies, but out of context, someone from another culture would not understand at all. Body in (E)motion Dramatic physical reactions to certain phenomena are common in manga and anime. These hugely exaggerated reactions are usually linked to some emotion, and, like the facial expressions, are drastically different from what Americans are familiar with. Gremlin’s World (a website) has a wonderful article on many of these reactions, including the nosebleed mentioned before. Other common physical reactions include falling down on the ground, which usually is a reaction to another character acting stupidly or an anticlimactic occurrence. Also, a very common physical reaction depicted above is the super-deformation of a character, whether of their entire body, or parts (usually the head). Super deformed style is often very simplistic (loss of defined fingers, nose, and usually very simple eyes) and seen as “cute,” and usually indicates an innocence, or lack of seriousness. Sometimes character’s faces will become super deformed when extreme emotions are being felt, and not just innocent ones. Often times when a character feels extreme anger, their head will be drawn hugely with most of their face becoming a wide mouth with sharp teeth as they yell at whatever it is upsetting them. Many of these physical reactions are seen as utterly ridiculous to Americans, and may see them as out of place in darker stories, however it is simply another example of cultural and contextual differences. Conclusion We have seen many of the differences between comics and manga, however there are still many not mentioned. The only real way to see them is to pick up a copy of each type and see for oneself. The study of visual texts is still relatively new, introduced to semiotic theory in the early 70’s by Rudolf Arnheim and John Berger. Their books introduced the idea that visual representation plays a crucial role in human understanding. However we cannot forget that graphic novels are still telling a story. Despite the cultural differences between the art and means of communication, many of the stories being written are similar to one another. The idea that stories cross-culturally differ only in detail is called “narratology,” coined by Tzvetan Todorov and first conceptualized by Algirdas Greimas. Through the differences between comics and manga, we can still see that the narrative code is still in effect for both styles. And it is important to realize that there are many, many other cultures who have their own graphic novels that adhere to their own cultural codes. Language barriers notwithstanding, since all these graphic novels will still follow the basic narrative code, anyone could look at a comic strip and determine some feel for what was going on, even if they can’t understand what is being said. A truly excellent relation of emotions in comics requires no lines to read, but a visual interpretation of signs to convey the meaning. Bibliography 1. Carrier , David - “The Aesthetics of Comics” - 2000 2. Danesi, Marcel - “The Quest for Meaning: A guide to semiotic theory and practice” - 2007 3. Gravett, Paul - “Graphic Novels: Stories to Change Your Life” - 2005 4. Lunning, Frenchy, ed. - “Mechademia, Vol. 3: Limits of the Human” - 2008 5. McCloud, Scott - “Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art” - 1993 Web Sources 1. Cohn, Neil - “Japanese Visual Language: The Structure of Manga” – Emaki.net http://www.emaki.net/essays/japanese_vl.pdf 2. Cohn, Neil - “Cross-Cultural Space…” – Emaki.net http://www.emaki.net/essays/spatial.pdf 3. Goldberg, Carey - “Cultural Insights” – The Boston Globe http://www.boston.com/news/science/articles/2008/03/03/cultural_insights/ 4. Goodman, Martin - “Deconstruction Zone 1…” – Animation World Magazine http://mag.awn.com/index.php?ltype=acrmag&category2=&article_no=2005&page=1 5. “Gremlin” - “Is that a nosebleed…” – Gremlin’s World http://zageek.wordpress.com/2008/02/22/is-that-a-nosebleed-or-are-you-just-happyto-see-me/ 6. Lima, Rafael - “History of Comic Books” – The Comic Book Home Page http://www.geocities.com/soho/5537/hist.htm 7. Mosley, Micheal - “A Semiotic Analysis of Anime” – Micheal Mosley http://www.corneredangel.com/amwess/papers/semiotic_anime.html