Residence / Family Group N. 1 - Comisión Interamericana de

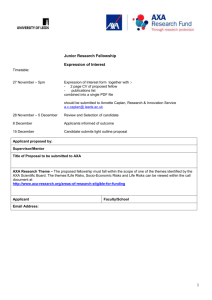

advertisement