Chapter 14 The White God Quetzalcoatl

advertisement

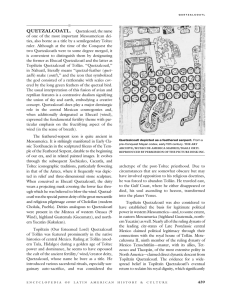

FOURTEEN The White God Quetzalcoatl And it came to pass, as they understood they cast their eyes up again towards heaven; and behold, they saw a Man descending out of heaven; and he was clothed in a white robe; and he came down and stood in the midst of them .... (3 Nephi 11:8) INTRODUCTION Virtually all 16th-Century writers wrote about a white god called Quetzalcoatl (KATESALL-CO-OUGHT-ALL). This tradition is strong and repetitive. Every school child in Mexico studies Quetzalcoatl and knows the importance of his role. The symbol of the serpent has long been associated with deities of Mexico and Guatemala. In the Aztec language, the word "coati" means serpent. By placing the Aztec word "quetzal" in front of the word "coatl," we have the word "Quetzalcoatl." The word "quetzal" means feathers. A beautiful bird, native to Guatemala, carries the name quetzal. Quetzalcoatl, therefore, means "feathered serpent," or serpent with precious feathers. (See Figure 14-1.) The word quetzal is the name of the coin in Guatemala and also is the national symbol of the country. Throughout pre-Columbian Mexican history, scores of individuals, both mythological and real, were given the name or title of Quetzalcoatl. Attempts also have been made to attribute the name Quetzalcoatl to only one person. The following quotations are indicative of what is said about Quetzalcoatl: In all of America's past no figure is more exciting, more tantalizing, or more frustrating than that of the Fair God Quetzalcoatl. (Irwin 1963:33) Quetzalcoatl was a man of comely appearance and serious disposition. His countenance was white, and he wore a beard. His manner of dress consisted of a long, flowing robe. (Ixtlilxochitl:45) Just as our era began with Christ, so that of the Aztecs and their predecessors began-approximately at the same time-with Quetzalcoatl. His image, the plumed serpent, had for pre-Columbian people the same evocative force as has the Crucifix for Christianity. (Sejoume 1957:25) The story of the life of the Mexican divinity, Quetzalcoatl, closely resembles that of the Savior; so closely indeed, that we can come to no other conclusion than that Quetzalcoatl and Christ are the same being. (Taylor 201) We should, however, exercise caution as we correlate Jesus Christ and Quetzalcoatl as identical personages because of the fact that a 10th-Century culture hero called Ce Acatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl took upon himself the title of the deity Quetzalcoatl. Nevertheless, the deity Quetzalcoatl apparently had its origin in the visit of Jesus Christ to the American continent. (See Allen 1970.) Similarities of Christ and Quetzalcoatl include the following: 1. Both Christ and Quetzalcoatl were recognized as creator of all things. (Mosiah 4:2; Saenz 1962:19, 40) 2. Both Christ and Quetzalcoatl were born of virgins. (Alma 7:10; Gamiz 95) 3. Both Christ and Quetzalcoatl are described as being white or as wearing a white robe. (3 Nephi 11:8; Torquemada 47) 4. Both Christ and Quetzalcoatl performed miracles. (3 Nephi 26:15; Sejoume 136-137) 5. Both Christ and Quetzalcoatl taught the ordinance of baptism. (3 Nephi 11:23; Irwin 1963:170) 6. Both Christ and Quetzalcoatl prophesied of future events. (Ixtlilxochitl:40) 7. Both Christ and Quetzalcoatl were universal as opposed to just being recognized as local gods. (3 Nephi 16:1; Sejoume 1962) 8. A great destruction was associated with both Christ and Quetzalcoatl at exactly the same time period in history. (3 Nephi 8:5; Ixtlilxochitl:40) 9. The cross was a symbol to both Christ and Quetzalcoatl. (3 Nephi 27:14; Irwin 1963:165) 10. Both Christ and Quetzalcoatl sent out disciples to preach their word. (3 Nephi 12:1; Wirth 1978:55) 11. Both Christ and Quetzalcoatl promised they would come a second time. (2 Nephi 6:14; Sahagun 1:40) 12. A new star is associated with both Christ and Quetzalcoatl. (3 Nephi 1:21; Anales de Cauhtitlan 7) 13. The children of both Christ and Quetzalcoatl will become lords and heirs of the earth. (4 Nephi 1:17; Ixtlilxochitl:40) Question: If the parallels are so strong between Christ and Quetzalcoatl, why do some people question that they are one and the same? Answer: From the time of Christ to the Conquest of Mexico, many priests and royalty were given the name of Quetzalcoatl. This practice suggests that Quetzalcoatl became a title in much the same way that Nephi became a title: Wherefore, the people were desirous to retain in remembrance his name. And whoso should reign in his stead were called by the people, second Nephi, third Nephi, and so forth, according to the reigns of the kings; and thus they were called by the people, let them be of whatever name they would. (Jacob 1:11) One such culture hero, named Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl and born c935 AD, left a trail from the Mexico City area to the Yucatan. The great Temple of Kukulcan was dedicated to this Toltec Quetzalcoatl. Kukulcan is the Maya word for feathered serpent. (Allen 1970:8694) The priest Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl set about to establish a new golden age, a reincarnation of a utopia that existed centuries earlier under the reign of the deity Quetzalcoatl. (Florescano 1964:164-166) Furthermore, many pagan attributes became associated with Quetzalcoatl over the years, either by another individual's being named Quetzalcoatl or by the people's entering into apostasy. A case in point is the Temple of Quetzalcoatl located by the pyramids of Teotihuacan. These stone serpents with feathers around their necks well represent a distorted view of Christ. (See Figure 14-2.) Question: If the parallels are so strong between Christ and Quetzalcoatl, why would Christ be associated with the serpent? Is not the serpent a symbol for Satan? Answer: In the Book of Mormon, the serpent is a symbol of Christ. (1 Nephi 17:41; 2 Nephi 25:20; Alma 33:19-21; Helaman 8:14-15) However, the event is couched in Old Testament history and recorded in the Book of Numbers. The children of Israel were residing in the wilderness. Being plagued with poisonous serpents, Moses prayed to the Lord for his people. The Lord instructed Moses to make a bronze serpent and attach it to a pole. The Lord promised Moses that anyone looking upon that serpent, made of brass, after having been bitten by a poisonous serpent, would live. (Numbers 21:6-9) Nephi, the son of Helaman in the Book of Mormon, provides an explanation of the meaning of the brazen serpent Moses lifted up on a pole: As he lifted up the brazen serpent in the wilderness, even so shall he be lifted up who should come. And as many as should look upon that serpent should live, even so as many as should look upon the Son of God with faith, having a contrite heart, might live, even unto that life which is eternal. (Helaman 8:14-15) John the Beloved portrayed the same type of symbolism as he wrote: And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of Man be lifted up. (John 3:14) SYMBOLISM OF THE QUETZAL AND THE SERPENT WITH CHRIST The symbolic association of Jesus Christ with the tradition of the white god, Quetzalcoatl, is indeed impressive. The fact that the serpent is associated with Satan in the Garden of Eden may suggest that Christ was originally associated with the serpent and that in the Garden of Eden, Satan, as the great counterfeiter, took upon himself the identity of Christ to deceive Eve. In that sense, Christ is the serpent, as illustrated in the Book of Mormon: And now, my brethren, I have spoken plainly that ye cannot err. And as the Lord God liveth that brought Israel up out of the land of Egypt, and gave unto Moses power that he should heal the nations after they had been bitten by the poisonous serpents, if they would cast their eyes unto the serpent which he did raise up before them, and also gave him power that he should smite the rock and the water should come forth; yea, behold I say unto you, that as these things are true, and as the Lord God liveth, there is none other name given under heaven save it be this Jesus Christ, of which I have spoken, whereby man can be saved. (2 Nephi 25:20) Behold, he was spoken of by Moses; yea, and behold a type was raised up in the wilderness, that whosoever would look upon it might live. And many did look and live. But few understood the meaning of those things, and this because of the hardness of their hearts. But there were many who were so hardened that they would not look, therefore they perished. Now the reason they would not look is because they did not believe that it would heal them. (Alma 33:19-20) A further symbolic representation of Christ with the quetzal bird and the coatl (serpent) may be as follows. The beautiful quetzal bird is symbolic of the heavens, and the serpent is symbolic of the earth. Christ is God over both heaven and earth. Christ descended, or condescended, to the level of man as He took upon himself flesh. As the serpent crawls along the ground, so was Christ humiliated as He was scourged and hung upon the cross. Like the quetzal, Christ ascended to heaven. Through the atonement of Christ and through our faith in Christ, we may also resurrect and have eternal life. In simple terms, if we were living at the time of Christ's appearance to the Nephites and if we were familiar with both the culture of Mesoamerica and the recorded prophecies of Christ in the scriptures, we might say: As Christ descended, His coming was like the beautiful quetzal bird. And after having taught us, He, again like the quetzal, ascended to heaven. And like the coatl (serpent), He came to earth and crawled through the dust of life and suffered death for us to gain eternal life. He was QUETZALCOATL. CHRIST IN THE BOOK OF MORMON The impact that the image of Quetzalcoatl has played in the history of Mexico is overwhelming. Of the pantheon of gods celebrated by the ancient Mexicans, only Quetzalcoatl reached all cultures. An author by the name of Laurette Sejoume of the University of Mexico was so impressed with this concept that she wrote a book called The Universality of Quetzalcoatl. Although the concept of god became polluted throughout the centuries and although other people took upon themselves the name or symbolism of Quetzalcoatl, the Book of Mormon itself sets the stage for the beginning of the Mesoamerican legend of Quetzalcoatl: And it came to pass that while they were thus conversing one with another, they heard a voice as if it came out of heaven; and they cast their eyes round about, for they understood not the voice which they heard; and it was not a harsh voice, neither was it a loud voice; nevertheless, and notwithstanding it being a small voice it did pierce them that did hear to the center, insomuch that there was no part of their frame that it did not cause to quake; yea, it did pierce them to the very soul, and did cause their hearts to bum. And it came to pass that again they heard the voice, and they understood it not. And again the third time they did hear the voice, and did open their ears to hear it; and their eyes were towards the sound thereof; and they did look steadfastly towards heaven, from whence the sound came. And behold, the third time they did understand the voice which they heard; and it said unto them: Behold my Beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased, in whom I have glorified my name-hear ye him. And it came to pass, as they understood they cast their eyes up again towards heaven; and behold, they saw a Man descending out of heaven; and he was clothed in a white robe; and he came down and stood in the midst of them; and the eyes of the whole multitude were turned upon him, and they durst not open their mouths, even one to another, and wist not what it meant, for they thought it was an angel that had appeared unto them. And it came to pass that he stretched forth his hand and spake unto the people, saying: Behold, I am Jesus Christ, whom the prophets testified shall come into the world. (3 Nephi 11:3-10) Every Book of Mormon prophet from Lehi to the coming of Christ prophesied of this singular, important event. Figure 14-3 is an illustration of Christ drawn by Cliff Dunston. It emphasizes the characteristics of the bearded god as spoken of by the Spanish chroniclers. QUETZALCOATL IN TRADITION Not all statements about Quetzalcoatl refer to Christ. The following poem, however, reflects the stature that the symbol of Quetzalcoatl played in the lives of the ancient Mesoamericans: The Prophet All the glory of the godhead Had the prophet Quetzalcoatl; All the honor of the people. Sanctified his name and holy; And their prayers they offered to him In the days of ancient Tula. There in grandeur rose his temple; Reared aloft its mighty ramparts, Reaching upward to the heavens. Wondrous stout and strong the walls were; High the skyward-climbing stairway, With its steps so long and narrow, With its many steps so narrow That there scarce was room for setting, Room for placing of the footsteps. There he lies full-length extended; Lies outstretched and ever mantled, With his features closely covered. Glory he of all the nations; And his face is like unto a Mighty echo-sounding fire-flame That has just been fully muffled; Pitilessly been extinguished. See, his beard is very lengthy; See, exceeding long his beard is; Yellow as the straw his beard is! And his people, they the Toltecs, Wondrous skilled in all the trades were, All the arts and artifices, So that naught there was they knew not; And as master workmen worked they. Fashioned they the sacred emeralds; Fashioned they the precious turquoise; Smelted they both gold and silver. Other arts and trades they mastered; In all crafts and artifices Skilled were they as wondrous workmen. And in Quetzalcoatl all these Arts and crafts had their beginning; In him all were manifested. He the master workman taught them All their trades and artifices. Houses had he wrought of emeralds; Dwellings made of gold and silver; Edifices worked from coral; Had his palace built of sea-shells And his wondrous habitations Fashioned in artistic woodwork And adorned with precious feathers. And his people, they the Toltecs, Called he from the distant places. Swiftly came they running to him; Very swiftly came they running; Wondrous fast of foot the racers. And they named them for their swiftness The tlancuacemilihuime, They whose legs are never wearied Running from sunrise to sunset. And nearby there was a mountain Called the Hill of Tzatzitepec; Called the Hill of Loud-outcrying. Still unchanged today its name is. Thereto went the public crier; Thereon stood he when they called him. Far o'er all the land he shouted Such commands as there was need of, Called so very loudly that his Every word was heard afar off. All commands from there he thundered; Every mandate there he issued; Every order there he sent forth. Quickly running came the Toltecs: Swiftly came they from afar off, Wondrous fast to hear the orders, Know the will of Quetzalcoatl. Very rich was Quetzalcoatl. Nothing pleasing to the palate; Nothing helpful to the body Ever lacked they there in Tula. Very large there grew the squashes; Wondrous big and stout the squashes So that one could scarcely span them With the outstretched arms embracing. Very long and thick the com ears So that in their arms they bore them. Stoutly grew the amaranth stocks; Wondrous tall the amaranth stocks; And like trees they used to climb them. Ready colored grew the cotton, Red and yellow, rose and purple, Green and bluish, verdigris, Black and orange, gray and crimson, Blushing like the ripening berry. Ready colored grew the cotton And no need was there to dye it. Variegated, many-colored Were the birds in ancient Tula. There the bluish xiutotol; There the quetzal and zacuan; There the red-necked Tlauhquechol; Birds of every hue and color; Birds that sang with wondrous sweetness Songs that gladdened all the listeners. Wealth untold there was in Tula; Emeralds and gold uncounted; Treasures unsurpassed they guarded. And they grew the chocolate berry; Grew the flowering cacahuate. Far o'er all the land extended Stood the chocolate plantations. Wondrous rich were all the Toltecs; Masters they of wealth uncounted; Every need was satisfied them; Nothing lacked they in their households; Hunger never dwelt among them; And the small com never used they Save to heat their thermal baths with. Quetzalcoatl offered penance And with thorns his legs he punctured Till the blood came oozing outward. Ever bathed he in the night-time; Bathed he in the Xippacoyan, In the Bathing Place of Xipe. And thus custom imitated They the sacred fire expenders; They the priests officiating Kept the mode of Quetzalcoatl, Master of their organization And creator of their being; Kept the usages of Tula, Even as today we keep them; Here in Mexico observe them. (Cornyn 1931:78-85) THE 10TH-CENTURY QUETZALCOATL Apparently,just as a Mexican tradition today prescribes that children be named after great people, such as Jesus or Moses, the title or name of Quetzalcoatl was adopted by other people. Hence, "Quetzalcoatl," as stated earlier, became a title much in the same way that "Nephi" became a title after the death of Nephi, the son of Lehi. (Jacob 1:11) That apparent tradition has caused a great deal of confusion and even a great deal of misinformation. (See Figure 14-4.) So the reader will not be confused, a treatise is given below about a 10th-Century Mexico culture hero who took upon himself the title, or the name, of Quetzalcoatl. This Quetzalcoatl is the one who migrated from the Mexico Valley to the Yucatan where he built the Temple of Kukulcan at Chichen Itza. Kukulcan is the Maya word for Quetzalcoatl. Quetzalcoatl is Aztec. Most written material about Quetzalcoatl today refers to the 10th-Century Quetzalcoatl. The material that follows under this heading is derived from Chapter 3 of "A Comparative Study of Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered-Serpent God of Meso-America, with Jesus Christ, the God of the Nephites" (Allen 1970:75-80). In the past number of years and among all the pre-Spanish themes, there has been an over abundance of literature relative to the great Mesoamerican myth or legend of Quetzalcoatl. Nevertheless, in spite of the abundant amount of literature that has reference to this fascinating American myth or legend, the ancient figure of Quetzalcoatl continues to be developed in an inextricable mythological and legendary cord that creates a desire to want to know the real history. Perhaps the obscurity and confusion that is current today regarding the myth or legend of Quetzalcoatl can be attributed to the great exaggerated mythological subjectivity that is prevalent in a study of this type, and perhaps the problem lies with the myth or legend itself. According to Florescano (1964:121-122), every person who has studied the Quetzalcoatl legend has elaborated on it and has inculcated his own personal myth. Apparently, all students of Quetzalcoatl work from the hypothesis that he was the great god of the Aztecs as well as other ancient Mesoamerican tribes. Therefore, we need not be surprised that everyone has taken a little information from one source and another to develop a personal myth. There are a number of reasons that may suggest that any treatise on the personality of the feathered serpent would have subjective overtones. Paramount among these is the type of source material available for a study of this nature. All that is known about Quetzalcoatl comes in the form of secondary sources. All of the written information about Quetzalcoatl that is available today has an origin in the writings ofthel6th-Century Spanish chroniclers. As mentioned earlier, the Spanish chroniclers were those Spanish conquerors, Catholic missionaries, or natives, like Ixtlilxochitl, who had to use as source material the Aztecs and Mayas who were living at the time of the Conquest. They, in turn, had to relate those things which they could remember from the oral and written traditions passed on to them from centuries back. As a result, we can assume logically that the vast majority of material written in the 16th Century has the probability of being biased. Perhaps it would be biased from an Indian point of view in an attempt to protect the religious beliefs or biased on the part of the Spaniard in an attempt either to correlate the Mexican history with Christianity or to present the opposite point of view and to equate the history of the Mexicans with workings of the devil. A second problem that occurs in an attempt to be objective in a study of Quetzalcoatl arises from the fact that on many occasions it is difficult, if not impossible, to determine whether the Spanish chroniclers were writing about human beings who were named Quetzalcoatl or whether the chroniclers were indeed referring to the myths and legends that date back to the god Quetzalcoatl. The major problem that arises in the study of Quetzalcoatl originates from the discussion of two distinct personalities, neither one having an apparent relationship with the other. On the one hand, Quetzalcoatl is seen as a human being existing in the 10th Century, filled with passions, fighting with his people, and finally exalted to the position of a god. The god Quetzalcoatl, on the other hand, seems to have a long life span with information about him beginning prior to the time of the Christian era and proceeding forward. The latter is considered in the annals as the Creator God of the earth and even man himself. Sejourne (1962:15-16), commenting on the extreme difficulty of separating the divine from the human in Quetzalcoatl, suggested that this is because Quetzalcoatl jumps from one time period to another and from one city to another. In reality, his giant figure fills the scene during hundreds of years without any interruption. We must, therefore, consider Quetzalcoatl in all of his fabulous amplitude, accepting what he must have been, perhaps more profound than a personal king, to the extent that the Nahuatl nation declared him as their creator. Armillas (1947:163) proposed a solution to the problem in his writings. He said that in the Mexican myth and tradition, Quetzalcoatl presents distinct human and divine characteristics. We must, therefore, examine each separately to determine the age of the different individual concepts and to verify when and how they were integrated to constitute the complete figure of the 16th Century. Modem writers and archaeologists have amplified the Quetzalcoatl dilemma. Krickburg (1964:135) wrote, "Quetzalcoatl ... had ... the function of a cultural hero character which resembled that of the Supreme Deity." Coe explained: They (the Toltecs) were ruled by a great king who took on the title of the mighty Mesoamerican god Quetzalcoatl (Feathered Serpent), and the doings of this man have been forever mixed up with those more properly ascribed to the god. (Coe 1962:13) Leon-Portilla recorded: In the firm relationship with the worship of the ancient supreme deity, Quetzalcoatl, it is known that among the Toltecs there was a priest by the name of Quetzalcoatl who sought to maintain the purity of the traditional worship. (Leon-Portilla 1968:36) Leonard also analyzed the Quetzalcoatl problem and t mistaken identity by modem historians: As a youth, Topiltzin studied for the priesthood and eventually became a high priest of Quetzalcoatl, or the Feathered Serpent, the very ancient god of Teotihuacan and the patron of learning and civilized skills. When Topiltzin ascended the Toltec throne, he changed his own name to Quetzalcoatl. This was not an act of self-deification; high priests of the time were often called by the names of the gods they worshipped. But the change of name caused endless confusion. Both ancient Indian legend- makers and modem historians have often mistaken Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, the man, for Quetzalcoatl, the god. (Leonard 1967:59) In addition, Bushnell affirmed the Quetzalcoatl problem he wrote: The god who is most prominent in the art of Tula is the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl.... Confusion has been caused by the adoption of the name by the ruler who founded the city ... around whom many legends have gathered. (Bushnell 1965:53-54) The human characteristics are interwoven with the divine attributes of Quetzalcoatl to the extent that writers are forced to exclude one or the other or to create two or more Quetzalcoatls. Dr. Daniel Brinton wrote at the close of the last century and interpreted Quetzalcoatl as follows: This ... national hero ... was often identified with the supreme deity and the creator of the world.... He personally appeared among the ancestors of the nation, and taught them ... framed the laws which governed their social relations, and ... he left them, not suffering death but disappearing in some way from their view. Hence it was nigh universally expected that at some time he would return. (Brinton 1882:27) A single summary statement as recorded by Peterson (1959:68) is ample to synthesize the Quetzalcoatl problem: "History seems to become infused with legend, and confuses the individual Ce Acatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl with the deity Quetzalcoatl whom he served." To add more confusion to the picture, I should point out that the culture hero, about whom the above authors wrote, existed centuries earlier, stemming from the featheredserpent motif or perhaps even adopting the feathered-serpent motif. The 10thCentury culture hero has been labeled by several titles. These titles are Topiltzin, Ce Acatl, Nacxipi, and some have associated him with Ehecatl. All of these names appear with the appendage of Quetzalcoatl. Topiltzin, translated, means "Our Lord," and only Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, of all of the gods of Mesoamerica, is called Lord, and there is even evidence to indicate that men swore by him. (Spence 1923:127) The Quetzalcoatl problem is intensified because Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl is attributed a virgin birth. He is depicted as wearing a long robe and of having the appearance of a white and bearded man. He also left Mexico with the promise he would return. Ce Acatl is another name used to identify the 10th-Century Mesoamerican culture hero; and the name is synonymous with Topiltzin-that is, both names appear to refer to the same individual. Ce Acatl is simply the day on which Topiltzin was born.1 1 Ancient kings or leaders rather commonly adjusted their birthdays to correlate with the birthday of a great previous leader. Thus, Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl not only may have adopted the name of Quetzalcoatl but also may have adopted his birthday-not the same year but the same month and day. From almost all of the accounts dealing with Quetzalcoatl, agreement is reached that Topiltzin Ce Acatl took upon himself the name of the deity whom he and his people worshipped. CONCLUSIONS The following conclusions regarding the life of the culture hero Topiltzin Ce Acatl Quetzalcoatl seem appropriate: Topiltzin translated into the English means "Our Lord." This name carries suggestive overtones of supreme deity. Ce Acatl is the date given as the birth of Quetzalcoatl and corresponds to the Christian dating period of AD 935-947. Topiltzin Ce Acatl has been described as having a virgin birth, wearing a long robe, and of being white and bearded. Topiltzin Ce Acatl is refer-red to as a Toltec king who reigned in Tula, Cholula, and other parts of Mesoamerica. Topiltzin Ce Acatl is portrayed as having succumbed to adultery and taking his own life. Topiltzin Ce Acatl is referred to in other accounts as having left toward the east, with a promise to return some day to reconquer his domain. Montezuma is recorded as having expected the return of Topiltzin Ce Acatl and indeed thought he had returned when the Spaniards came in the year Ce Acatl [1519] and realized the Conquest. A great deal of confusion still seems to rest among the scholars of Mesoamerica as they attempt to unravel the life of Topiltzin Ce Acatl from that of the deity Quetzalcoatl who existed centuries earlier and whose name Topiltzin Ce Acatl took upon himself. An attempted correlation between Jesus Christ and Quetzalcoatl referred to above does not present itself as a serious problem for two reasons: First, this Quetzalcoatl apparently had no reference to the deity Quetzalcoatl, and second, in referring to an earlier quote, we must expect the deity Quetzalcoatl to become paganized throughout the centuries even as the characteristics of Jesus have been changed. During the period of more than one thousand years' time that elapsed between the close of the Nephite history (A.D. 421) and the discovery of America in 1492, no doubt the polluting of the true gospel continued to in crease, resulting in corrupted, apostate, and untrue pagan practices. The worship of numerous gods, with religious beliefs and practices ranging from witchcraft to rather noble and true spiritual expressions, prevailed through out the Americas. The peculiar thing is that such extremes in religious beliefs and practices could have existed side by side in the religious expressions of the same peoples. Enough perverted truths remained, however, in clearly defined forms to make possible the identification of Quetzalcoatl and his religion as adulterated forms and counterfeits of Christ and the true gospel which he established in ancient America shortly following his resurrection. (Hunter 113) SUMMARY The symbolism of Christ associated with the serpent motif is indeed strong throughout Mesoamerica. This symbolism manifests itself in the Tree-of-Life Stone at Izapa and in the stepped-fret motifs in the ruins of Mitla. The temple of Kukulkan at Chichen Itza is associated with a 10th-century Toltec hero, Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl. (See Figure 14-5.) The origin of the name or title of Quetzalcoatl in all probability came about as a result of the visit of Christ to the Nephites. As time elapsed, other people took upon themselves the title or name of Quetzalcoatl. This practice is common today among the Mexican people as parents name their children after important people, including Jesus.