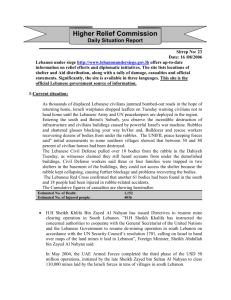

I- Introduction - Human Rights in Lebanon website, human rights

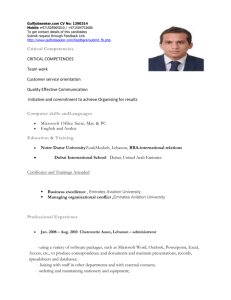

advertisement