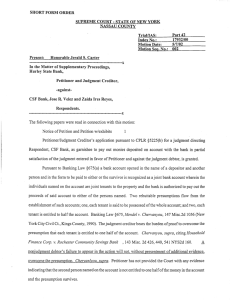

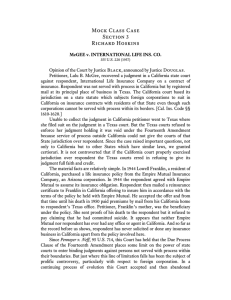

SUPREME COURT DECISIONS

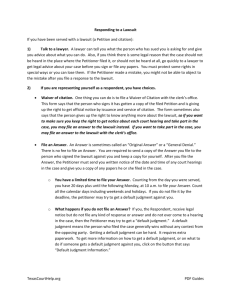

advertisement