E-Learning Report - Office of the Vice

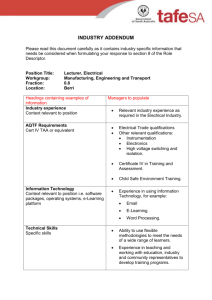

advertisement