Shmos73 - Internet Parsha Sheet

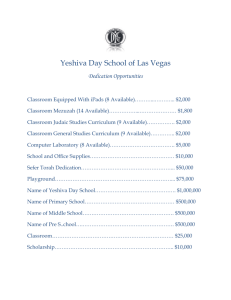

advertisement