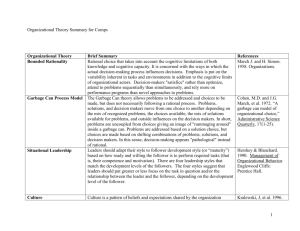

Relationally-Embedded Network Ties

advertisement