Anatomy_and_Physiolo..

advertisement

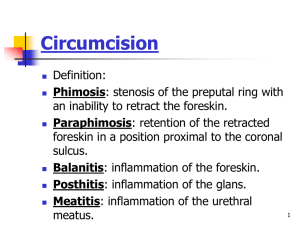

Male and Female Circumcision, edited by Denniston et. al Kluwer Academic I Plenum Publishers, New York, 1999. pp. 9-18. THE ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE HUMAN PREPUCE Steve Scott INTRODUCTION 1. IN UTERO DEVELOPMENT OF THE GENITALIA Until the seventh week of gestation, the genitalia of the embryo are female in appearance. Around the eighth week, male hormones initiate the development of the ma1e reproductive organs. Both male and female genitalia evolve from the same embryonic tissue (Figure 1). The genital tubercle becomes the glans clitoridis in the female and the glans penis in the male. The labioscrotal swellings become the labia majora in the female and the scrotum in the male. The urethral groove remains open in the female, creating the vaginal orifice. Around the fourteenth week, the urethral groove closes in the male as the urogenital folds fuse on the ventral aspect (underside) of the penis, creating the penile raphe. In the female, the urogenital folds become the labia minora. In 1992, I conducted a series of interviews with physicians in Salt Lake City, Utah. Among other questions, interviewees were asked what knowledge they had of the nature and function of the prepuce. Aside from the ability of a few to recite a passage from a pamphlet produced by the American Academy of Pediatrics1 (in which the prepuce is described as tissue that protects the glans penis), most physicians were ignorant of the anatomy and physiology of the genital structures they were routinely removing from infants and children. Subsequent research revealed the reason for their lack of knowledge. Most relevant medical texts contain no information regarding the anatomy and physiology of the prepuce. Some do not even include the prepuce in diagrams of the penis.2 Often, the only thing a medical student will learn about the prepuce is the manner in which it will be excised. Impelled by the logical premise that, if a body part exists, it may very well serve a purpose, I began my own research. Using MEDLINE, I collected information that identifies the prepuce as an exquisitely designed, highly innervated and vascularised complex of specialised erogenous structures that are vital to natural and normal sexual function. As this information finds its way into the hands of healthcare professionals, it is hoped that they will be able to inform parents more fully about what is lost to circumcision. Figure 1. Similarities in male and female genital anatomy. Adapted from Ritter TJ, Denniston GC.Say No to Circumcision! 2nd ed. Aptos: Hourglass. 1996;11-13. Used by permission of publisher. 1.1. Development of the Male Prepuce and Frenulum 2.1. Balanopreputial Membrane Around the twelfth week of gestation, the prepuce begins its development as a fold of tissue originating at the coronal sulcus (the groove that demarcates the shaft from the glans). The fold inverts (the outside becoming the inside) as it grows forward over the glans. 3 Shared epidermal cells of the glans and the advancing prepuce create a common balanopreputial membrane which firmly attaches the prepuce to the glans. The complete enfolding of the glans by the prepuce is accomplished by the twenty-fourth week (Figure 2). The fusion of the prepuce on the ventral aspect of the glans creates the frenulum, a bridge-like structure that joins the ventral prepuce to the glans.4 A common membrane binds the prepuce to the glans penis in the fetus and neonate. This is the same binding mechanism that fuses the eyelids of newborn kittens. This shared membrane inhibits the retraction of the prepuce and thereby protects the developing mucosae of the infantile glans and inner prepuce from faecal contamination. The desquamation of this membrane, resulting in the separation of the prepuce from the glans, is gradual and variable from individual to individual.6 Whorls of cells form in the membrane and die from the inside of the whorls out, creating hollows. Over time these hollows coalesce to form the preputial space, the zone between the prepuce and the glans. 7 2.2. Preputial Musculature One to two millimetres under the penile skin lies a smooth muscle sheath known as the dartos fascia.8 The muscle fibres of the dartos fascia form a mosaic pattern along the penile shaft skin and arrange themselves in a circular sphincter-like configuration at the tip of the prepuce. 9 The sphincteric action of this muscle can inhibit preputial retraction. This should be seen as normal physiology rather than a pathological condition. This sphincteric closing mechanism, beyond the urinary meatus, allows for the passage of urine while guarding against the entrance of foreign pathogens into the preputial space. Figure 2. Embryological development of the male prepuce. 2. THE EVOLUTION OF THE PREPUCE FROM INFANCY TO MATURITY Only 4% of newborn males have a fully retractable prepuce.s The remaining 96% are non-retractable due to two normal physiological conditions. 2.3. Preputial Development in Adolescence and Maturity The tubular, tapered, and elongated prepuce of the young boy should not be seen as "hypertrophic" or "redundant" tissue that requires "trimming." (Figure 2F) As the corpora cavernosa (the bodies that fill with blood to create an erection) develop in adolescence, the penis will enlarge to "take up the slack."10 A prepuce that in childhood appears long, may, at maturity, fail to completely cover the glans. A recent study published in the Journal of Urology finds that by ages 8 to 10, fifty percent of boys will have a fully retractable prepuce.l1 3. BLOOD SUPPLY 5.2. The Mucocutaneous Junction The blood supply to the prepuce arises from the inferior external pudendal artery.12 There are four branches of this artery. Two enter the superficial fascia dorsolaterally (upper sides) and two enter ventrolaterally (lower sides). These arteries are reflected towards the coronal sulcus where they anastomose (connect) with collaterals of the dorsal arteries. The blood supply to the frenulum arises from the dorsal arteries, which at this point have become dorsolateral13 Venous drainage is accomplished by way of multiple small veins that join the superficial dorsal veins, which, in turn, drain into the saphenous vein. The area where the outer prepuce meets the inner mucosa is known as the muco- cutaneous junction. Like the junctional regions of the eyelids and lips, the quantity and specia1isation of nerve endings increase in these transitional zones.17 4. HISTOLOGY The mucosa of the inner prepuce is lined by stratified squamous epithelium, similar to the frictional mucosa of the vagina. As with other frictional mucosae, such as the lining of the inner eyelid, the mouth, and the esophagus, the mucosal aspect of the prepuce has a great capacity for selfrepair. The neural and vascular networks of the preputial mucosa rise higher in the dermis, thereby favouring more acute sensation.14 5.3. Nerve Endings Numerous specialised nerve endings have been identified in the prepuce.l3-22 Among them are: paccinian corpuscles (responsible for sensing pressure); Ruffini's corpuscles (mechanoreceptors); end-bulbs of Krause (most likely responsible for sensing cold); free nerve endings (pain receptors); and, perhaps the most important in terms of erogenous sensation, Meissner's corpuscles, which are sensitive to light touch. 6. ADULT PREPUTIAL MORPHOLOGY Most of the skin that covers the human body is attached to underlying structures. The skin covering the eyes and the penis are exceptions (Figure 3). 5. INNERVATION The dorsal and lateral aspects of the prepuce are innervated by the dorsal penile nerve. The ventral prepuce and frenulum are innervated by the perinea1"nerve.15 The dorsal and perineal nerves are branches of the pudendal nerve, which derives from the second, third, and fourth sacral plexus. 5.1. Neonatal Innervation There is an extensive network of nerves within the prepuce at birth. Newborns appear to have a higher density of preputial nerves than adults.16 Figure 3: Anatomy of the penis and prepuce. 6.1. The Penile Skin System The penile skin's proximal (toward the body) point of attachment occurs at the base of the penile shaft. The skin extends distally covering the shaft, riding up and over the corona glandis and the glans. At a point, usually near the distal (away from the body) extremity of the glans, the skin doubles back under itself. In this area, the skin trans-itions into a mucous membrane, which runs proximally in contact with the mucous membrane of the glans. It continues up and over the corona glandis, ultimately finding its circumferential point of attachment at the coronal sulcus. 6.2. The Preputial Mucosa The mucosa of the inner prepuce is comprised of two distinct dermatological zones: the ridged mucosa; and the smooth mucosa. 6.3. The Ridged Mucosa The ridged mucosa is a pleated band that occurs near the mucocutaneous junction. It contains 10 to 12 transverse ridges, whose collective width is 10 to 15cm.23 Clusters of the tactile nerve endings of Meissner (Meissner's corpuscles) are found in abundance in the crests of these ridges. They are not present in the sulci (furrows) between the ridges.24 6.4. Smooth Mucosa The smooth mucosa constitutes the remainder of the inner pre-puce, from the ridged band to the coronal sulcus. frenulum, which connects the tongue to the floor of the mouth, frenula tether movable structures to non-movable structures. The lingual frenulum, for example, not only prevents the tongue from being swallowed, but also restricts movement of the tongue in the distal direction. The preputial frenulum restricts proximal movement of the ridged band and assists in returning the prepuce to its distal position over the glans. 7. LANGUAGE Originally, the word prepuce (or foreskin) referred to the skin in front of the glans penis. In fact, the style of circumcision practised by the ancient Hebrews until 140 CE involved only the removal of the skin that protruded beyond the tip of the glans.25 A style of circumcision promoted in 1917 involved the excision of a large section of the penile shaft skin and subsequent suturing of the distal and proximal skin remnants.26 Given individual differences in penile skin length, the ongoing variability in circumcision techniques, and the ability of the penile skin to change shape under differing circumstances, it may benefit our understanding of this penile skin system and facilitate a more accurate means of describing its physiology if we were to abandon the notion of fore skin and instead view the penile integument as a continuous sheath. 8. PHYSIOLOGY The penile skin system is unique in its form and function. No other part of the human anatomy possesses the ability to evert and invert like the movable penile skin sheath. 8.1. Protection 6.5. The Frenulum On the ventral aspect of the glans, the point of attachment of the prepuce is advanced towards the meatus and forms the frenulum, a bridgelike structure that is continuous with the ridged band. Like the labiogingival frenulum, which connects the upper lip to the upper gum and the lingual It has been noted that the prepuce protects the sensitive glans in infancy, and that this protection lasts throughout life.27 Given the limited sensitivity of the glans in relation to the highly innervated inner prepuce,28 one could argue that the outer layer of the prepuce protects the inner layer, while the glans serves the prepuce by giving it form. The ridged mucosa of the prepuce is so highly vascularised that a vascular blush is often apparent at this site.29 This high degree of vascularisation combined with the ability of the dartos fascia to contract and draw the penis closer to the body in the presence of cold adds another element of protection. 8.2. Lubrication The glans penis, like the glans clitoridis, is designed as an internal organ. This internalisation insures that both the epithelia of the inner prepuce and the glans remain smooth and moist. This enclosed environment maintains the suppleness of both of these structures. 8.4. Intercourse Upon full erection, there is ample play in the penile skin to allow the glans to glide in and out of the prepuce. During the inward motion of intercourse (Figure 5), the ridged mucosa, positioned now near the midpenile shaft, glides along and in contact with the vaginal wall. The Meissner's corpuscles in the crests of the ridged mucosa are stimulated by this contact and by the restraint of the frenulum, with which the ridged mucosa is continuous. In the outward motion of intercourse, the prepuce inverts over the distal portion of the penis. The Meissner's corpuscles are again stimulated, this time by contact with the corona glandis. 8.3. Erection Upon erection, the prepuce everts, supplying the penis with ample integument to accommodate its increased size, while deploying the ridged mucosa in an oblique circumferential position on the penile shaft (Figure 4). Figure 4. Eversion of the prepuce upon erection, with exposure of ridged band along shaft. Figure 5. Action of the prepuce in sexual intercourse. Adapted from Ritter TJ, Denniston GC. Say No to Circumcision! 2nd ed. Aptos:Jurglass. 1996;12-14. Used by permission of the publisher. 9. THE ANATOMICAL AND PHYSIOLOGICAL CONSEQUENCE OF CIRCUMCISION Circumcision diminishes the penis, removing approximately half of the penile skin.30 One study found that the amount of tissue lost to living adult males ranged from 64 to 90 square centimetres.31 Circumcision results in the excision of both the outer and inner prepuce. The circumferential line of excision usually occurs near the coronal sulcus, and in many cases may involve penile shaft skin. In the United State, the standard techniques of neonatal circumcision almost always result in the excision of the frenulum. The resultant ablation of the specialised nerve endings found in these regions irreversibly desensitises the penis, rendering it incapable of experiencing the full range of sensual and sexual sensations afforded the intact male. Circumcision externalises the glans, thereby exposing it to the abrasive friction of clothing. The inevitable keratinisation, drying, and callousing of the mucosal lining of the glans further erodes penile sensitivity. The unique ability of the penis to glide in and out of itself is dependent on a complete penile integument. The diminution of this integument limits or precludes the important role of penile skin mobility in sexual foreplay. During sexual intercourse, the penile skin sheath enfolds the distal portion of the penis, thereby conserving coital lubrication (Figures 5). In the absence of penile skin mobility, a relatively static structure is created. The resulting dowel-like penis with its mushroom-shaped head draws lubrication from the vagina with each outward motion of intercourse, increasing abrasion and loss of lubrication. 10. CONCLUSION Historically, certain parts of human anatomy have been deemed redundant or superfluous. The adenoids, mastoids, and tonsils fell into this category. It was not until researchers identified the functions of these organs that they were spared indiscriminate excision, and given their due respect. Even the appendix, by its very name considered an appendage to the body, is now known to be part of the immune system, producing large numbers of lymphocytes. The fact that routine circumcision in America has become institutionalised may explain why some people find it difficult to ascribe any value or function to the prepuce. An overwhelming body of primary research, however, demonstrates that the prepuce does, in fact, have a wide range of valuable functions. The prepuce is not a redundant part of human anatomy. It is, rather, a complex of specialised erogenous structures that work in sympathy with adjacent penile structures. It is not a "superfluous tag of skin," as some would describe it, but a large platform for the reception and expression of sensual and sexual sensation. The prepuce is not an appendage to the penis, but a continuum of the specialisation that distinguishes male genital anatomy. REFERENCES 1. American Academy of Pediatrics. Newborns: Care of the Uncircumcized [sic] Penis. Evanston: American Academy of Pediatrics. 1984. 2. See: Snell RS. Atlas of Clinical Anatomy. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. 1978:136. 3. Glenister TW. A consideration of the processes involved in the development of the prepuce in man. Br J Urol 1956;28:243-9. 4. Hunter RH. Notes on the development of the prepuce. J Anat 1935;70:68-75. 5. Gairdner D. The fate of the foreskin. BMJ 1949;2:1433-7. 6. Gairdner D. The fate of the foreskin. BMJ 1949;2:1433-7. 7. Hunter RH. Notes on the development of the prepuce. J Anat 1935;70:68-75. 8. Jefferson G. The peripenic muscle: some observations on the anatomy of phimosis. Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics 1916;23:177-81. 9. Woolsey G. Applied Surgical Anatomy. New York: Lea Brothers. 1902:405-7. 10. Jefferson G. The peripenic muscle: some observations on the anatomy of phimosis. Surgery, Gynecology, and Obstetrics 1916;23:177-81. 11. Kayaba H, Tamura H, Kitajima S, Fujiwara Y, Kata T, Kata T. Analysis of shape and retractability of the prepuce in 603 Japanese boys. J Urol 1996;156:1813-5. 12. Hinman F. The blood supply to preputial island flaps. J Urol 1991;145:1232-5. 13. Juskiewenski S. A study of the arterial blood supply to the penis. Anatomia Clinica 1982;4:1017. 14. Winkelman RK. The erogenous zones: their nerve supply and its significance. Proceedings of the Staff Meetings of the Mayo Clinic 1959;34:39-47. 15. Kaneko S. Penile Electrodiagnosis penile peripheral innervation. Urology 1987;30:210--2. 16. Winkelmann RK. The cutaneous innervation of human newborn prepuce. J Invest Dermatol 1956;26:53-67. 17. Winkelman RK. The erogenous zones: their nerve supply and its significance. Proceedings of the Staff Meetings of the Mayo Clinic 1959;34:39-47. 18. Ghmori D. Uber die Entwicklung der Innervation der Genitalapparate als Peripheren Aufnahmeapparat der Genitalen Reflexe. Zeitschrift far Anatomie und Entwicklungsgeschichte 1924;70:347410. 19. De Girolano A, Cecio A. Contributo alla conoscenza dell'innervazione sensitiva del prepuzio nell'uomo. Bollettino della Societa Italiana de Biologia Sperimental. 1968;44:1521-2. 20. Winkelmann RK. The cutaneous innervation of human newborn prepuce. J Invest Dermatol 1956;26:53-67. 21. Bazett HT, McGlone B, Williams RG, Lufkin HM. Depth, distribution and probable identification in the prepuce of sensory end-organs concerned in sensations of temperature; thermometric conductivity. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry 1932;27:484-515. 22. Taylor JR, Lockwood AP, Taylor AJ. The prepuce: specialized mucosa of the penis and its loss to circumcision. Br J Urol 1996;77:291-5. 23. Taylor J. The prepuce: specialized mucosa of the penis and its loss to circumcision. Transcript of Presentation at the Second International Symposium on Circumcision. May 1, 1991. 24. Taylor JR, Lockwood AP, Taylor AJ. The prepuce: specialized mucosa of the penis and its loss to circumcision. Br J Urol 1996;77:291-5. 25. Kohler K. Circumcision. In: Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: KTAV Publishing House, Inc. 1964:93. 26. Austin FD, Sharpe TG. Circumcision. New York Medical Journal 1917;106:787-88 27. American Academy of Pediatrics. Newborns: Care of the Uncircumcized [sic] Penis. Evanston: American Academy of Pediatrics. 1984. 28. Halata Z, Munger BL. The neuroanatomical basis for the protopathic sensibility of the human glans penis. Brain Res 1986;371:205-30. 29. Taylor JR, Lockwood Ap, Taylor AJ The prepuce: specialized mucosa of the penis and its loss to circumcision. Br J Urol 1996;77:291-5. 30. Taylor JR, Lockwood AP, Taylor AJ. The prepuce: specialized mucosa of the penis and its loss to circumcision. Br J Urol 1996;77:291-5. 31. Werker PM, Terng AS, Kon M. The prepuce free flap: Dissection feasibility study and clinical application of a super-thin new flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;102:1075-82. The following quote relating to the “circumcision decision” is from an interview with Dr. John R. Taylor, co-author of “The prepuce: specialized mucosa of the penis and its loss to circumcision.” British Journal of Urology 1996;77:291-295. The prepuce is a structure in its own right and it has to be given a value before you make any decision. This is specialized skin and mucous membrane. It's built very much like the lips, or the vulva in the female; it's a junction between skin and the inner lining. It contains highly specialized nerve endings, which are only found in a few places in the body, and we only find this sort of tissue in areas where it has to perform specialized function, and this specialized function has to do with sex. This is sexual tissue, and there's no way you can avoid the issue. Most people look at the child and the prepuce, and say that, well, the prepuce isn't much use for a child. Well, the prepuce isn't designed for a child, it's designed for an adult and you can't look at it in childish terms. FOR MORE INFORMATION: www.doctorsopposingcircumcision.org/video/prepuce.html www.cirp.org/pages/anat/ www.coloradonocirc.org/anatomy www.cirp.org/library/anatomy/taylor Fine-touch pressure thresholds in the adult penis Morris L. Sorrells, James L. Snyder, Mark D. Reiss, Christopher Eden, Marilyn F. Milos, Norma Wilcox, Robert S. Van Howe. Finetouch pressure thresholds in the adult penis. British Journal of Urology (BJU) International, April 2007, Volume 99, Issue 4, pages 864-9. In April 2007, a landmark study was published in the British Journal of Urology, which demonstrates conclusively that circumcision harms the sensitivity of the penis. It contains a literature review of other evidence relating to the effects of circumcision on sexuality. This is the first study to measure the sensitivity of the foreskin itself compared to other parts of the penis; previous studies have only compared the glans of the circumcised penis vs. the glans of the intact penis. It is also the first to map multiple anatomical points instead of testing just one point each on the glans or shaft. CONCLUSIONS: The transitional region from the external to the internal prepuce is the most sensitive region of the uncircumcised penis and more sensitive than the most sensitive region of the circumcised penis. Circumcision ablates the most sensitive parts of the penis. Full study article available for download at: http://www.nocirc.org/touch-test/bju_6685.pdf Comparative fine-touch sensitivity of selected regions of the penis and foreskin (adapted from Semmes-Weinstein testing data in Sorrells et al., 2007). Taller bars indicate greater fine-touch sensitivity. The most sensitive parts of the intact penis are missing from the circumcised penis. Key: Light (front bars): circumcised penis Dark (rear bars): intact penis