The Amygdala and Depression

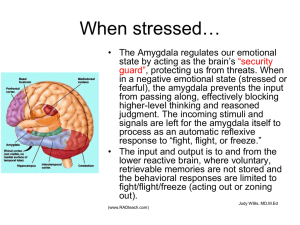

advertisement

Amygdala From Scholarpedia Joseph E. LeDoux (2008), Scholarpedia, 3(4):2698. revision #37515 [link to/cite this article] Curator: Dr. Joseph E. LeDoux, Center for Neural Science, NYU, New York, NY Image:Amygdala article by LeDoux.jpg Figure 1: Location of amygdala in the brain. Amygdala's Inner Workings Researchers gain new insights into this structure's emotional connections By Harvey Black The amygdala, an almond-sized and -shaped brain structure, has long been linked with a person's mental and emotional state. But thanks to scientific advances, researchers have recently grasped how important this 1-inch-long structure really is. Associated with a range of mental conditions from normalcy to depression to even autism, the amygdala has become the focal point of numerous research projects. Derived from the Greek for almond, the amygdala sits in the brain's medial temporal lobe, a few inches from either ear. Coursing through the amygdala are nerves connecting it to a number of important brain centers, including the neocortex and visual cortex. "More and more we're beginning to believe, and the evidence is pointing to the idea, that it's the circuits that are important, not just the structure per se," says Ned Kalin, professor of psychiatry, University of Wisconsin-Madison. "And in this particular case the circuitry between the frontal cortical regions of the brain may be critical in regulating emotion and in guiding emotion-related behaviors." Investigations detailing the amygdala's role date back more than 60 years. H. Kluver and P.C. Bucy reported that amygdala lesions transformed feral rhesus monkeys into tame ones.1 But these lesions were so large and, 1 compared to today's techniques, so crude, that researchers weren't sure of the structures responsible for the behavioral changes. Improved techniques, such as using the neurotoxin ibotenic acid to make more precise lesions; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); and positron emission tomography (PET) scans of the amygdala's activity, are partly responsible for renewed interest in the amygdala. A second reason, says John Aggleton, professor of cognitive neuroscience at Cardiff University, Wales, was rat research conducted by Joseph Ledoux, professor of neural science and psychology at New York University, and Michael Davis, professor of psychiatry at Emory University.2,3 This research, says Aggleton, has, in the past 10 years, "paid enormous dividends in understanding how fearful stimuli can control behavior." But Kalin notes that David Amaral, professor of psychiatry and neuroscience, University of California, Davis, has demonstrated a major difference between rats and monkeys in the links between the amygdala and the rest of the brain.4 "[Amaral's] work has pointed out that there are very strong connections between the amygdala and the neocortex, particularly the visual cortex and the prefrontal cortex. There's not much cross-talk in the rodents between the amygdala and the cortex," says Kalin. Amaral says he thinks that the amygdala is really playing a protective role. "It is a very phylogenetically old structure," he says. "Probably very early on in Phylogeny, [it] was primarily involved in protecting organisms, moving them away from obnoxious chemical milieu. As organisms evolved it got different kinds of sensory information in to evaluate stimuli in the environment, and that's one of the reasons why it's more highly connected with the neocortex as organisms evolved. It's getting more and more highlevel information to do an interpretation of what's going on in the environment." Kalin's recent monkey study5 shows how a lesioned amygdala can damage that potentially life-saving evaluative function. "We found that when we selectively lesioned the amygdala in 3-year-old animals, the animals' acute fear responses were blunted," he says. Amaral has found that lesioned adult monkeys abandon their normal caution and tendency to withdraw when confronted with a strange monkey. Instead, they approached the animal and showed "greater frequency and duration of 2 positive social behavior," such as grooming and cooing, than did nonlesioned monkeys. A Role in Autism? Lesioned infant monkeys, however, present a dramatically different picture. Jocelyne Bachevalier, professor of neurobiology and anatomy, University of Texas Health Science Center, found that 6-month-old monkeys, their amygdalas lesioned four months before,6 "will not initiate social approach as young babies normally do to play together. And they also seem to have ritualistic behavior, like rocking. These behaviors remained when they became adults," she says. Bachevalier believes that the damaged amygdala robs the young animals of their ability to interpret the social world around them. "I have the feeling that these animals have a hard time interpreting facial expressions or any type of gestures the monkeys can have. Thus they react as trying to avoid interactions," she says. So striking were these findings, says Bachevalier, that she examined literature on human emotional problems. "When I was starting to read about autism, the behavioral syndrome looked quite similar," she says. "Maybe the amygdala is important in the social deficits we see in this population of humans." She was following up on this hypothesis when Tropical Storm Allison, which hit the Houston area in early June, drowned her study animals. But Amaral questions whether amygdala lesions in neonatal animals can be used as an autism model. Based on Bachevalier's findings, Amaral lesioned infant monkeys to explore the possible connection,7 and placed them in a cage with an intact monkey. "We expected to see these neonatal monkeys not responding in a social way, like Jocelyne suggested.... We found that the animals did not engage in social interactions, but they are very vigilant and very attentive to the other monkey in the cage. If this was going to be a model of autism, they should show no interest in the other animal. You can get lack of social behavior in a variety of ways. If you're phobic, it's not that you can't read social signals; it's just that you're frightened. That's what our monkeys look like. They're frightened," he says. But Amaral doesn't dismiss the possibility that some amygdala dysfunction could play a role in autism. He is currently using magnetic resonance imaging to examine amygdala function in autistic children and adults. The Amygdala and Depression 3 Other researchers are exploring how the amygdala might affect people who suffer from bipolar or unipolar (depression-marked melancholy episodes) illnesses, which run in families. "We found that [such people] have an abnormal increase in blood flow and glucose metabolism," says Wayne Drevets, chief of mood and anxiety disorders in the National Institute of Mental Health's neuroimaging section. He also reports that in patients with unipolar depression, the amygdala's left side is smaller by about 12 percent to 15 percent than it is in normal controls.8 Why this is so is not fully certain, but Drevets notes that the amygdala is linked with other brain structures, including the orbital frontal cortex, the thalamus, the striatum, all of which have been "implicated in emotional processing," he says. The overactive amygdala could be a sign of excitotoxicity, a lethal kind of overactivity that kills cells. That, Drevets suggests, might be why a shrunken amygdala is seen in depressed patients. And, he says, some anti-depressive drugs, like lithium, increase biochemical production; these protect neurons from the ravages of overexcitation, thus giving researchers a good reason to continue developing anti-depressants. While the amygdala is involved in current emotional responses, it is also heavily involved in emotional memory, notes psychology professor Larry Cahill, University of California, Irvine. It gives a "critical boost for longterm memory of emotional events," he says, also noting that men's and women's amygdalas respond differently to emotional situations. The brain images of women and men were recorded while they were shown emotionally upsetting films, such as plane crashes or killer whales dismembering and eating baby seals. Men showed an increase in glucose metabolism on the amygdala's right side; women showed the increase on the structure's left side. The findings, notes Cahill, don't explain the difference, but they force researchers to explore the basis for it.9 "To my mind, it's saying we have to stop ignoring these kinds of variables [sex differences] when we try to figure out how the brain stores memory for emotional events. Though we only reported the amygdala, in the whole brain we found very different patterns," he says. "We have to now actively incorporate the influence of gender into our theorizing about how the brain stores memories for emotional events, because men and women on average, are probably not doing it in the same way." 4 Harvey Black (73773.2227@compuserve.com) is a freelance writer in Madison Wis. 1. H. Kluver, P.C. Bucy, "Preliminary analysis of the temporal lobes in monkeys," Archives of Neurological Psychiatry, 42:979-1000, 1939. 2. J. Ledoux et al., "Different projections of the central amygdaloid nucleus mediate autonomic and behavioral correlates of conditioned fear," Journal of Neuroscience, 8:2517-9, 1988. 3. M. Davis, "The role of the amygdala in fear and anxiety," Annual Review of Neuroscience, 15:353-75, 1992. 4. D.G. Amaral et al., "Anatomical organization of the primate amygdala complex." In: The Amygdala, J. Aggleton, ed., New York: Wiley-Liss, 1992, pp 1-67. 5. N.H. Kalin, "The primate amygdala mediates acute fear but not the behavioral and physiological component of anxious temperament," The Journal of Neuroscience, 21:2067-74, March 15, 2001. 6. J. Bachevalier, "Medial temporal lobe structures and autism: A review of clinical and experimental findings," Neuropsychologia, 32:627-48, 1994. 7. M. Prather et al., "Dissociation of fear to inanimate objects from social fear in macaque monkey with neonatal bilateral amygdala lesions," Neuroscience, in press. 8. W. Drevets, "Neuroimaging and neuropathological studies of depression: implications for the cognitive-emotional features of mood disorders," Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 11[2]:240-49, April 2001. 9. L. Cahill et al., "Sex related difference in amygdala activity during emotionally influenced memory storage," Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 75:1-9, January 2001. Refs and further reading 5 The amygdaloid region of the brain (i.e. the amygdala) is a complex structure involved in a wide range of normal behavioral functions and psychiatric conditions. Not so long ago it was an obscure region of the brain that attracted relatively little scientific interest. Today it is one of the most heavily studied brain areas, and practically a household word. This article will summarize the anatomical organization of the amygdala and its functions. Contents [hide] 1 Anatomical organization 2 Function 3 Conclusion 4 References 5 See Also Anatomical organization The existence of the amygdala was first formally recognized in the early 19th century. The name, derived from the Greek, was meant to denote the almond-like shape of this region in the medial temporal lobe. Much debate has since ensued, and continues today, about how the amygdala should be subdivided. Also controversial is how the subdivisions relate to other major regions of the brain. One long-standing idea is the amygdala consists of an evolutionarily primitive division associated with the olfactory system (the cortico-medial region) and an evolutionarily newer division associated with the neocortex (the basolateral region). The cortico-medial region includes the cortical, medial, and central nuclei, while the basolateral region consists of the lateral, basal and accessory basal nuclei. The almond shaped structure that originally defined the amygdala only included the basal nucleus rather than the whole structure now considered to be the amygdala. A proposal by Swanson and Petrovich (1998) challenges the idea that “the amygdala” exists as a structural unit. Instead, it proposes that the amygdala consist of regions that belong to other regions or systems of the brain and 6 that the designation “the amygdala” is not necessary. For example, in this scheme, the lateral and basal amygdala are viewed as nuclear extensions of the cortex (rather than amygdala regions related to the cerebral cortex), while the central and medial amygdala are said to be ventral extensions of the striatum. While this scheme has some merit, the present review focuses on the organization and function of nuclei and subnuclei that, while are traditionally said to be part of the amygdala, nevertheless perform their functions regardless of whether they are part of the cortex, striatum or the amygdala (for more information see Striatum and Cerebral cortex). Figure 2: Some areas of the amaygdala, as shown in the rat brain. The same nuclei are present in primates, including humans. Different staining methods show amygdala nuclei from different perspectives. Left panel: Nissl cell body stain. Middle panel: acetylcholinesterase stain. Right panel, silver fiber stain. Abbreviations of amygdala areas: AB, accessory basal; B, basal nucleus; Ce, central nucleus; itc, intercalated cells; La: lateral nucleus; M, medial nucleus; CO, cortical nucleus. Non-amygdala areas: AST, amygdalostriatal transistion area; CPu, caudate putamen; CTX, cortex. It is easy to be confused by the terminology used to describe the amygdala nuclei, as different sets of terms are used. This problem is especially acute with regards to the basolateral region of the amygdala. One popular scheme refers to the basolateral region as consisting of the lateral, basal and accessory basal nuclei. Another scheme uses the terms basolateral and basomedial nuclei to refer to the regions named as the basal and accessory basal nuclei in the first scheme. Particularly confusing is the use of the term basolateral to refer to both a specific nucleus (the basal or basolateral nucleus) and to the larger region that includes the lateral, basal and accessory basal nuclei (the basolateral complex). The major nuclei of the amygdala are shown in sections from the rat brain in Fig. 1. Figure 3: Some of the major input and output connections of the amygdala. Sensory abbreviations: aud, auditory; vis, visual; somato, somatosensory; gust, gustatory (taste); olf, olfactory. Modulatory arousal systems abbreviations: NE, norepinephrine, DA, dopamine, ACh, acetylcholine; 5HT, serotonin). 7 Figure 4: Inputs to some specific amygdala nuclei. Abbreviations of amygdala areas: basal; B, basal nucleus; Ce, central nucleus; itc, intercalated cells; LA: lateral nucleus; M, medial nucleus. Sensory abbreviations: aud, auditory; vis, visual; somato, somatosensory; gust, gustatory (taste). Figure 5: Outputs of some specific amygdala nuclei. Abbreviations of amygdala areas: basal; B, basal nucleus; Ce, central nucleus; itc, intercalated cells; LA: lateral nucleus. Modulatory arousal systems abbreviations: NE, norepinephrine, DA, dopamine, ACh, acetylcholine; 5HT, serotonin). Other abbreviations: parasym ns, parasympathetic nervous system; symp ns, sympathetic nervous system. Figure 6: Flow of sensory information to the lateral amygdala and through amygdala circuits to output systems. Abbreviations of amygdala areas: basal; B, basal nucleus; Ce, central nucleus; itc, intercalated cells; LA: lateral nucleus; M, medial nucleus. Modulatory arousal systems abbreviations: NE, norepinephrine, DA, dopamine, ACh, acetylcholine; 5HT, serotonin). The amygdala has a wide range of connections with other brain regions, allowing it to participate in a wide variety of behavioral functions. Some of the major connections are shown in Figure 3. Different nuclei of the amygdala have unique connections (Figures 4, 5, and 6), which is why each nucleus makes unique contributions to functions. A thorough discussion of all the connections is beyond the present scope. Therefore, a few key examples will be given. The lateral amygdala is a major site receiving inputs from visual, auditory, somatosensory (including pain) systems, the medial nucleus of the amygdala is strongly connected with the olfactory system, and the central nucleus connects with brainstem areas that control the expression of innate behaviors and associated physiological responses. In many instances, the subnuclei of a given nucleus also have distinct connections. The lateral nucleus, for example, includes dorsal, medial, and ventrolateral subnuclei, while the central nucleus contains lateral, capsular, and medial subnuclei. The dorsal subnucleus of the lateral nucleus receives much of the direct sensory flow to the amygdala, while the medial division of the central nucleus is the part that connects with response control regions. 8 Most of the inputs to the amygdala involve excitatory pathways that use glutamate as a transmitter. These inputs form synaptic connections on the dendrites of excitatory principal neurons that transit signals to other regions or subregions of the amygdala or to extrinsic regions. Principal neurons are thus also called projection neurons since the project out. However, axons of principal neurons also give rise to local connections to inhibitory interneurons that then provide feedback inhibition to the principal neurons. In addition to terminating on projection neurons, some of the excitatory inputs to the amygdala terminate on local inhibitory interneruons that in turn connect with principal neurons, giving rise to feedforward inhibition. The scheme of connections just described applies to the neurons of the basolateral complex moreso than to neurons within the corticomedial group. For example, while the projection neruons of the basolateral group are excitatory, the projection neurons in the central nucleus tend to be inhibitory in nature. Thus, excitation of neurons in the central nucleus leads to inhibition of target neurons, while inhibition of these projection neruons gives rise to increased output of the target neruons. Whether central amygdala cells are activated by excitatory projection neurons or by way of connections from projection neurons to local interneurons thus influences the ultimate output state of the central amygdala. These connections are consistent with the notion described above that the basolateral gruoup is closely associated with the cerebral cortex and the corticomedial group with the basal ganglia. The flow of information through amygdala circuits is modulated by a variety of neurotransmitter systems. Thus, norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine released in the amygdala influences how excitatory and inhibitory neurons interact. Receptors for these various neuromodulators are differentially distributed in the various amygdala nuclei. Also differentially distributed are receptors for various hormones, including glucocorticoid and estrogen. Numerous peptides receptors are also present in the amygdala, including receptors for opioid peptides, oxytocin, vasopressin, corticotripin releasing factor, and neuropetide Y, to name a few. Function In the late 1930s, researchers observed that damage to the temporal lobe resulted in profound changes in fear reactivity, feeding, and sexual behavior. Around mid century, it was determined that damage to the amygdala 9 accounted for these changes in emotional processing. Numerous studies subsequently attempted to understand the role of the amygdala in emotional functions, especially fear. The result was a large and confusing body of knowledge about the functions of the amygdala because much of the research ignored the nuclear and subnuclear organization of the amygdala, which was not fully appreciated, and partly because the functions measured by behavioral tasks were not well understood. Figure 7: Auditory fear conditioning paradigm. Studies using this paradigm have helped elaborate the functional role of amygdala nuclei. Rats are habituated to the chamber on day 1 (no stimulation). On day 2, the rat receives a small number of training trials (typically 1-5) in which a tone CS is paired with a footshock US. Controls receive unpaired presentations of the CS and US. On day 3, the CS is presented in a novel chamber with a unique odor (peppermint) and fear responses (freezing) to the CS assessed. Animals receiving pairings on day 2 show high levels of freezing but animals receiving unpaired training show little freezing. The early studies of fear used avoidance conditioning tasks. These measure fear in terms of how well an animal leans to avoid shock. However, avoidance is a two stage process in which Pavolvian conditioning establishes fear responses to stimuli that predict the occurrence of the shock, and then new behaviors that allow escape from or avoidance of the shock, and thus that reduce the fear elicited by the stimuli, are learned. In the 1980s, researchers began to use tasks that isolated the Pavlovian from the instrumental components of the task to study the brain mechanisms of fear. This strategy allowed a focus on the fear reaction conditioned by the shock rather than on behaviors that avoid the shock. In Pavlovian fear conditioning a neutral conditioned stimulus (Cs) that is paired with a painful shock unconditioned stimulus (US) comes to elicit fear responses such as freezing behavior and related physiological changes (Fig 7). Studies in rodents have mapped the inputs to and outputs of amygdala nuclei and subnuclei that mediate fear conditioning. In particular, it is widely accepted that convergence of the CS and US leads to synaptic plasticity in the dorsal subregion of the lateral amygdala. When the CS then occurs alone later, it flows through these potentiated synapses to the other amygdala targets and ultimately to the medial part of the central nucleus, outputs of 10 which control conditioned fear responses (Fig 8). Much has been learned about the cellular and molecular mechanisms within lateral amygdala cells that underlie the plastic changes. In brief, convergence of the strong US inputs to cells that also receive CS inputs results in an elevation of intracellular calcium, and event that triggers a host of molecular responses leading to protein synthesis (Fig 9). The proteins then help strengthen stabilize the CS input synapses, allowing them to respond more strongly to the CS after conditioning. As a result, the CS flows through the amygdala circuits to elicit the fear responses controlled by the central nucleus. Amygdala areas, togehter with the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, is invovled in the reduction of learned fear through extinction and cogntive regualatory processes. Figure 8: Auditory fear conditioning pathways. The auditory conditioned stimulus (CS) and somatosensory (pain) unconditioned stimulus (US) converge in the lateral amygdala (LA). The LA receives inputs from each system via both thalamic and cortical inputs. CS-US convergence induces synaptic plasticity in LA such that after conditioning the CS flows through the LA to activate the central amygdala (CE) via intraamygdala connections. CE in turn controls the expression of behavioral (freezing), autonomic and endocrine responses that are components of the fear reaction. Other abbreviations: B, basal amygdal; CG, central gray; LH, lateral hypothalamlus; ITC, intercalated cells of the amygdala; PVN, paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamlus. Although fear is the emotion best understood in terms of brain mechanisms, the amygdala has also been implicated in a variety of other emotional functions. A relatively large body of research has focused on the role of the amygdala in processing of rewards and the use of rewards to motivate and reinforce behavior. As with aversive conditioning, the lateral, basal, and central amygdala have been implicated in different aspects of reward learning and motivation, thought the involvment of these nuclei differs somewhat from their role in fear. The amygdala has also been implicated in emotional states associated with aggressive, maternal, sexual, and ingestive (eating and drinking) behaviors. Less is known about the detailed circuitry involved in these emotional states than is known about fear. 11 Because the amygdala learns and stores information about emotional events, it is said to participate in emotional memory. Emotional memory is viewed as an implicit or unconscious form of memory and contrasts with explicit or declarative memory mediated by the hippocampus. In addition to its role in emotion and unconscious emotional memory, the amygdala is also involved in the regulation or modulation of a variety of cognitive functions, such as attention, perception, and explicit memory. It is generally thought that these cognitive functions are modulated by the amygdala's processing of the emotional significance of external stimuli. Outputs of the amygdala then lead to the release of hormones and/or neuromodulators in the brain that then alter cognitive processing in cortical areas. For example, via amygdala outputs that ultimately affect the hippocampus, explicit memories about emotional situations are enhanced. For example, glucocorticoid hormone released into the blood stream via amygdala activity travels to the brain and then binds to neurons in the basal amygdala. The latter then connects to the hippocampus to enhance explicit memory. There is also evidence that the amygdala can, through direct neural connections, modualte the function of cortical areas. Over the past decade, interest in the human amygdala has grown considerably, spurred on by the progress in animal studies and by the development of functional imaging techniques. As in the animal brain, damage to the human amygdala interferes with fear conditioning and functional activity changes in the human amygdala in response to fear conditioning. Further, exposure to emotional faces potently activates the human amygdala. Both conditioned stimuli and emotional faces produce strong amygdala activation when presented unconsciously, emphasizing the importance of the amygdala as an implicit information processor and its role in unconscious memory. Studies of humans and non-human primates also implicate the amygdala in soical behavior. Findings regarding the human amygdala are mainly at the level of the whole region rather than nuclei. Figure 9: Intracellular signal transduction pathways underlying auditory fear conditioning in LA cells. Structural and/or functional changes in the amygdala are associated with a wide variety of psychiatric conditions in humans. Included are various 12 anxiety disorders (PTSD, phobia, and panic), depression, schizophrenia, and autism, to name a few. This does not mean that amygdala causes these disorders. It simply means that in people who have these disorders alterations occur in the amygdala. Because each of these disorders involves fear and anxiety to some extent, the involvement of the amygdala in some of these disorders may be related to the increased anxiety in these patients. Conclusion The rise in popularity of the amygdala as a research topic should not overshadow the fact that much remains to be learned. Especially important for the future will be studies that attempt to understand whether the importance of the amygdala in fear reflects the importance of fear to the amygdala or whether fear is just the function that has been studied most. References Aggleton J, ed (2000) The Amygdala: A Functional Analysis, 2nd Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Amaral DG (2003) The amygdala, social behavior, and danger detection. Ann NY Acad Sci 1000:337-47. Balleine BW, Killcross S (2006) Parallel incentive processing: an integrated view of amygdala function. Trends Neurosci 25: 272-279. Cardinal RN, Parkinson JA, Hall J, Everitt BJ (2002) Emotion and motivation: the role of the amygdala, ventral striatum, and prefrontal cortex. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 26: 321-352. Davis M (2006) Neural systems involved in fear and anxiety measured with fear-potentiated startle. Am Psychol. 61:741-56. Davis M, Walker DL, Myers, KM (2003) Role of the amygdala in fear extinction measured with potentiated startle. NeuroRx 3: 82-96. Dolan RJ (2007) The human amygdala and orbital prefrontal cortex in behavioural regulation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 362(1481):78799. 13 Everitt BJ, Cardinal RN, Parkinson JA and Robbins TW (2003) Appetitive behavior: impact of amygdala-dependent aspects of emotional learning. Ann NY Acad Sci 985: 233-250. Fanselow MS, Gale GD (2003) The amygdala, fear, and memory. Ann NY Acad Sci. 985:125-34. Holland P and Gallagher M (2004) Amygdala-frontal interactions and reward expectancy. Curr Opin Neurobiol 14: 148-155. LeDoux JE (1996) The Emotional Brain. New York: Simon and Schuster. Maren, S (2005) Synaptic mechanisms of associative memory in the amygdala. Neuron 47: 783-786. McDonald A (1998) Cortical pathways to the mammalian amygdala. Prog Neurobiol 55: 257-332. McGaugh JL (2003) Memory and Emotion: The making of lasting memories. London: The Orion Publishing Group. Paré D, Quirk, GJ, LeDoux JE (2003) New vistas on amygdala networks in conditioned fear. J Neurophysiol 92: 1-9. Phelps EA, LeDoux JE (2005) Contributions of the amygdala to emotion processing: from animal models to human behavior. Neuron 48:175-187. Pitkänen A, Savander V, LeDoux JE (1997) Organization of intraamygdaloid circuitries in the rat: an emerging framework for understanding functions of the amygdala. Trends Neurosci 20:517-523. Quirk GJ, Mueller D (2008) Nerual mechanisms of extinction learning and retrieval. Neuropsychopharmacology 33: 56-72. Rauch SL, Shin LM, Wright CI (2003) Neuroimaging studies of amygdala function in anxiety disorders. Ann NY Acad Sci 985:389-410. Rodrigues SM, Schafe GE, and LeDoux JE (2004) Molecular mechanisms underlying emotional learning and memory in the lateral amygdala. Neuron 44: 75-91. 14 Rolls, ET (1999) The Brain and Emotion. Oxford, Oxford University Press. Shinnick-Gallagher P, Pitkanen A, Shekhar, A, and Cahill L, eds (2003) The Amygdala in Brain Function: Basic and Clinical Approaches. New York, New York Academy of Sciences. Swanson LW, Petrovich GD (1998) What is the amygdala? Trends Neurosci 21:323-331. Internal references Peter Redgrave (2007) Basal ganglia. Scholarpedia, 2(6):1825. Valentino Braitenberg (2007) Brain. Scholarpedia, 2(11):2918. Nestor A. Schmajuk (2008) Classical conditioning. Scholarpedia, 3(3):2316. Joseph E. LeDoux (2007) Emotional memory. Scholarpedia, 2(7):1806. William D. Penny and Karl J. Friston (2007) Functional imaging. Scholarpedia, 2(5):1478. Howard Eichenbaum (2008) Memory. Scholarpedia, 3(3):1747. Peter Jonas and Gyorgy Buzsaki (2007) Neural inhibition. Scholarpedia, 2(9):3286. Wolfram Schultz (2007) Reward. Scholarpedia, 2(3):1652. Marco M Picchioni and Robin Murray (2008) Schizophrenia. Scholarpedia, 3(4):4132. + نوشته شده توسط11:21 و ساعت1387 نظر بدهید | در یکشنبه یکم اردیبهشت Peter Robinson and I still have a bet about the efforts to which the Clintons will go to pull out the election. We forget that even today, Sen. Clinton leads in both Ohio and Texas. 15 If she were to win both, and carry that momentum to Pennsylvania, again she will have won the key states in play in the November election — California, Florida, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas. It would be no small thing to end the primary season with the biggest states and the most recent victories. It might not be. Fear and the Amygdala Whether you are ecstatic, dejected or frightened, emotions certainly can have a grip on your life. In the world of science, however, emotions did not have such a hold. In the past they took a back seat to more clear-cut scientific topics. But now an increasing amount of evidence is showing that the emotion of fear is decipherable. The identification of a specific brain system that processes fear is spurring a great interest in the field. New discoveries could explain the mystery behind many mental disorders and prompt the development of new treatments. A bang against the window draws you out of a snooze. Clunk. Clunk. Clunk. You bolt upright. A shadow dances outside the window. Is it the serial killer you read about in the paper? An almond-shaped area of the brain, the amygdala (uh-mig-dah-la) receives signals of the potential danger and begins to set off a series of reactions that will help you protect yourself, according to an increasing number of studies. Clunk. Clunk. Clunk. Additional messages sent to the amygdala determine that the wavering image is only a branch. This time there is no need to bolt. The fear response is snuffed out and you return to sleep. Research is revealing the brain areas and mechanisms that are involved in this amygdala-based fear circuit. There is hope that the detailed understanding of how the brain processes fear will lead to: New methods to treat fear-related disorders such as phobias, where specific fears are taken to an extreme. Insights on how gender, age and illness affect fear interpretations. Researchers began to find evidence that the amygdala was involved in the emotion of fear in the late 1930s. Monkeys with damage to the brain cluster and surrounding areas had a dramatic drop of fearfulness. Later, studies showed that rats with targeted amygdala damage would snuggle up 16 to cats. For years, however, an understanding of how the amygdala fit into a brain system to process fear was unclear. Then starting in the 1970s some scientists began using precisely controlled study designs to systematically map the brain's fear system. Research in rodents revealed brain pathways, centering on the amygdala, that were preprogrammed to respond to danger. Accumulating revelations about this fear system led researchers recently to examine the human brain's response to fear with imaging studies. One study showed that pictures of frightening faces initiate a quick rise and fall of activity in the amygdala. In the future, scientists believe imaging techniques may help determine the course of treatment for disorders involving a malfunction in fear processing. For example, a person with an extreme fear of germs who continuously washes, known as an obsessivecompulsive disorder, often goes through months of behavioral therapy. The idea is to train the person to learn to overcome their fear. But what if imaging tests show that the amygdala is continuously active and does not diminish its activity over time as it normally would to a fearful stimulus? This could signify that the area is defective and a lifetime of therapy designed to alter behavior would not be able to stifle the fear response. In this case, drug treatment alone potentially may hold more benefits. Currently, researchers are further deciphering the fear process in humans. They hope to determine the effects of age, gender and illness on the system. In addition, scientists are uncovering the biochemical reactions that run the fear response and are searching for the brain regions that modify the response in the amygdala. They also are hunting for the brain structures that help store dreadful memories over time. Insight on the fear system also is motivating researchers to untangle the possible differences between fear and anxiety. Fear involves a quick hit-andrun process in the brain. Anxiety stirs a slower reaction that lasts a while. This suggests that the processing of the two emotions may be different. Indeed, early studies show that different parts of the amygdala may process anxiety versus fear. It also appears that some illnesses result from defects in these anxiety areas while others are more linked to fear paths. Researchers also are examining the role of the amygdala in less distressing types of emotions, such as happiness. Of course, after Pennsylvania votes on April 22, Indiana and North Carolina will vote on May 6, West Virginia will vote on May 13, Oregon and 17 Kentucky will vote on May 20, and South Dakota and Montana will end the caucus/primary season on June 3, six weeks after Victor Davis Hanson, Very Wise Man, thinks it does. For his sake, I hope someone else plans his trips for him. And his course schedule. Read The Rest Scale: 2 out of 5. (Obama is apt to win all of those elections I name.) Hanson's utterly shocking, and sure to be absolutely correct, conclusion: [...] I think this will continue to drag on, and the wounds among Democrats will deepen and fester to the extent that the real question by June is not whether McCain's base will stay with him (it probably will), but how many scarred and hurt Democrats won't cross over to a perceived moderate. Or maybe not. 2/21/2008 02:46:00 PM |permanent link| | Main Page | Other blogs commenting on this post | 0 comments I THINK NOT. The NY Times and veteran Thom Shanker, who should know better, tells us: [...] Completing a mission in which an interceptor designed for missile defense was used for the first time to attack a satellite, the Lake Erie, an Aegis-class cruiser, fired a single missile just before 10:30 p.m. The Lake Erie, as anyone who knows anything about U.S. Navy ships knows, is a Ticonderoga class cruiser. A common error: [...] Because the Aegis system dominates the ship's architecture, ships equipped with it are sometimes mistakenly called Aegis class ships. Correct. Thank you, Times! (I expect a correction will be forthcoming.) Read The Rest Scale: 4 out of 5. ADDENDUM, 2/21/08, 3:39 a.m.: Compare and contrast Gail Collins making the same points about how absurd the government story is that a gazilion other people have made, to the two lines in the news article coverage that: 18 [...] Separately, a Pentagon spokesman, Bryan Whitman, dismissed suggestions that the operation had been designed to test the nation’s missile defense systems or antisatellite capabilities or that the effort had been to destroy secret intelligence equipment. “This is about reducing the risk to human life on Earth, nothing more,†Mr. Whitman said. There's no lack of space experts available for quotes that this is beyond belief. But heaven forfend the news department question a Bush government spokesperson. 2/21/2008 01:11:00 AM |permanent link| | Main Page | Other blogs commenting on this post | 0 comments Wednesday, February 20, 2008 THEY'VE CARVED THE LETTERS "CHA" ONTO THE FACE OF THE MOON. Just look up tonight and see. Bring your own flashlight. Read The Rest Scale: 3.5 out of 5. 2/20/2008 01:18:00 PM |permanent link| | Main Page | Other blogs commenting on this post | 0 comments MONEY AND POLITICS, and the undue influence of wealth on politics, or, in other words, "campaign finance reform," is an issue I've long struggled to find good policy ideas about. Mark Schmitt helps greatly to clarify my thinking about it here. Read The Rest Scale: 3.75 out of 5, more if interested. Hey, better I post at all, even if I don't say more, right? Right? ADDENDUM, 6:57 p.m.: Another non-value-added link, the astute Henry Jenkins on the linguistic aspects of Obama's approach. RTR Scale: 4 out of 5. Via ObWi commenter Malixe here. 2/20/2008 01:06:00 PM |permanent link| | Main Page | Other blogs commenting on this post | 2 comments 19 Saturday, February 16, 2008 WHAT I CAN. Maya Soetoro-Ng, Barack Obama's half-sister talks about her brother. I SEE NO FUTURE AS A TRAVEL AGENT for Victor Davis Hanson, which is good for him, given his mad skilz at reading a schedule. He writes: Peter Robinson and I still have a bet about the efforts to which the Clintons will go to pull out the election. We forget that even today, Sen. Clinton leads in both Ohio and Texas. If she were to win both, and carry that momentum to Pennsylvania, again she will have won the key states in play in the November election — California, Florida, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas. It would be no small thing to end the primary season with the biggest states and the most recent victories. It might not be. Of course, after Pennsylvania votes on April 22, Indiana and North Carolina will vote on May 6, West Virginia will vote on May 13, Oregon and Kentucky will vote on May 20, and South Dakota and Montana will end the caucus/primary season on June 3, six weeks after Victor Davis Hanson, Very Wise Man, thinks it does. For his sake, I hope someone else plans his trips for him. And his course schedule. Read The Rest Scale: 2 out of 5. (Obama is apt to win all of those elections I name.) Hanson's utterly shocking, and sure to be absolutely correct, conclusion: [...] I think this will continue to drag on, and the wounds among Democrats will deepen and fester to the extent that the real question by June is not whether McCain's base will stay with him (it probably will), but how many scarred and hurt Democrats won't cross over to a perceived moderate. Or maybe not. 2/21/2008 02:46:00 PM |permanent link| | Main Page | Other blogs commenting on this post | 0 comments 20 I THINK NOT. The NY Times and veteran Thom Shanker, who should know better, tells us: [...] Completing a mission in which an interceptor designed for missile defense was used for the first time to attack a satellite, the Lake Erie, an Aegis-class cruiser, fired a single missile just before 10:30 p.m. The Lake Erie, as anyone who knows anything about U.S. Navy ships knows, is a Ticonderoga class cruiser. A common error: [...] Because the Aegis system dominates the ship's architecture, ships equipped with it are sometimes mistakenly called Aegis class ships. Correct. Thank you, Times! (I expect a correction will be forthcoming.) Read The Rest Scale: 4 out of 5. ADDENDUM, 2/21/08, 3:39 a.m.: Compare and contrast Gail Collins making the same points about how absurd the government story is that a gazilion other people have made, to the two lines in the news article coverage that: [...] Separately, a Pentagon spokesman, Bryan Whitman, dismissed suggestions that the operation had been designed to test the nation’s missile defense systems or antisatellite capabilities or that the effort had been to destroy secret intelligence equipment. “This is about reducing the risk to human life on Earth, nothing more,†Mr. Whitman said. There's no lack of space experts available for quotes that this is beyond belief. But heaven forfend the news department question a Bush government spokesperson. 2/21/2008 01:11:00 AM |permanent link| | Main Page | Other blogs commenting on this post | 0 comments Wednesday, February 20, 2008 THEY'VE CARVED THE LETTERS "CHA" ONTO THE FACE OF THE MOON. Just look up tonight and see. Bring your own flashlight. 21 Read The Rest Scale: 3.5 out of 5. 2/20/2008 01:18:00 PM |permanent link| | Main Page | Other blogs commenting on this post | 0 comments MONEY AND POLITICS, and the undue influence of wealth on politics, or, in other words, "campaign finance reform," is an issue I've long struggled to find good policy ideas about. Mark Schmitt helps greatly to clarify my thinking about it here. Read The Rest Scale: 3.75 out of 5, more if interested. Hey, better I post at all, even if I don't say more, right? Right? ADDENDUM, 6:57 p.m.: Another non-value-added link, the astute Henry Jenkins on the linguistic aspects of Obama's approach. RTR Scale: 4 out of 5. Via ObWi commenter Malixe here. 2/20/2008 01:06:00 PM |permanent link| | Main Page | Other blogs commenting on this post | 2 comments Saturday, February 16, 2008 WHAT I CAN. Maya Soetoro-Ng, Barack Obama's half-sister talks about her brother. Click To Play A good piece on some of Obama's earlier years, by Todd Purdum. View The Rest Scale: 5 out of 5; read the rest: 4 out of 5. 2/16/2008 05:26:00 PM |permanent link| | Main Page | Other blogs commenting on this post | 0 comments Thursday, February 14, 2008 NIXON DID IT. Since I didn't blog it the first time around, Ron Rosenbaum's 2005 account of why it's clear that Nixon ordered the Watergate burglary. 22 Read The Rest Scale: 4 out of 5. 2/14/2008 05:12:00 PM |permanent link| | Main Page | Other blogs commenting on this post | 0 comments NO EDIBLE DARTH VADER ON A STICK? Actual items proposed to George Lucas for Star Wars merchandising. There are 15 more, plus their story. Read The Rest Scale: 3 out of 5, but I won't Force you. Incidentally, Steve Brust has written a Firefly novel. Free professional fanfic is shiny! 2/14/2008 12:26:00 AM |permanent link| | Main Page | Other blogs commenting on this post | 3 comments Wednesday, February 13, 2008 ACTUALLY, WE THINK HE'S A NICE BOY WHO MADE GOOD. In Tennessee: If you thought race was an uncomfortable issue in the Democratic presidential primary, wait 'til you get a load of what's going on in the Democratic primary in the Memphis area's 9th District of Tennessee, where a shockingly worded flier paints Jewish Rep. Steve Cohen (DTenn.) as a Jesus hater. "Memphis Congressman Steve Cohen and the JEWS HATE Jesus," blares the flier, which Cohen himself received in the mail -- inducing gasps -- last week. Circulated by an African-American minister from Murfreesboro Tenn., which isn't even in Cohen's district, the literature encourages other black leaders in Memphis to "see to it that one and ONLY one black Christian faces this opponent of Christ and Christianity in the 2008 election." 23 Cohen's main opponent in the August 5 Democratic primary in his predominantly African-American district is Nikki Tinker, who is black. The Commercial Appeal wrote an editorial in Wednesday's paper condemning Tinker for not speaking out against the anti-Semitic literature. "What does Nikki Tinker think about anti-Semitic literature being circulated that might help her unseat 9th District Congressman Steve Cohen in the Democratic primary next August?" the editorial asked. "The question goes to the character of the woman who wants to represent the 9th District, and 9th District voters deserve an answer. But Tinker declined to return a phone call about the flier." If Jesus moved next door, we'd invite him over for dinner, actually. Really. Read The Rest Scale: 2.5 out of 5. 2/13/2008 01:45:00 PM |permanent link| | Main Page | Other blogs commenting on this post | 1 comments Tuesday, February 12, 2008 LET US ALL PAY ATTENTION TO HENRY KISSINGER, because he is most wise in the ways of the world. When Kissinger offers advice on policy and the future, who shouldn't listen? Gather round: [...] As Mr. Kissinger said in his remarks: “I don’t know what a blog is. I don’t know how to find a blog.†His computer, he said, is used to read newspapers. [...] Mr. Kissinger said he was skeptical about the digitalization of media, for if his words and sentences “get shortened for cyberspace, there is no telling what will come out.†[...] The world is undergoing three types of transformation, Mr. Kissinger argued: the collapse of the state system, the shift of the global center of gravity from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and an emerging set of problems that can only be dealt with on a global basis. And he largely 24 agreed with Mr. Podhoretz’s assertion that the most important global conflict, which was once the cold war, is now the struggle against terrorism by Islamic radicals. “This is a war against radical Islam that has to be won,†said Mr. Kissinger, who was national security adviser and then secretary of state in the Nixon and Ford administrations, from 1969 to 1977. Let me get this straight: this is a world in which radical Islamists, who certainly do exist, have a large worldwide web of jihadi internet sites, on which they post war videos, and exhorations. This distributed network, and its nature, both as an internet presence, and as a form of asymmetric warfare and propagand is absolutely key to the nature of the actual terrorist threat, and we're supposed to listen to the advice of someone who doesn't even know what a blog is? The thing about cyberspace is the way we're forced to shorten everything, because unlike traditional media, we have a finite limit on how much we can quote, unlike newspapers, radio, and tv? That's Henry Kissinger's keen insight into the flaws of "digital media"? Definitely the man with the key to understanding 21st century international politics and relations. Read The Rest Scale: 2 out of 5 unless you wish to contemplate details of the prestigious Power Line book award, or somesuch, and note who shows up for it. Oh, and of course the award went to Norman Podheretz: who else? ADDENDUM, 2/14/08, 3:11 p.m.: A Times blog ended up quoting this: Here’s an interesting trackback to City Room’s Kissinger post from Tuesday [....] Thanks, City Room! 2/12/2008 06:27:00 PM |permanent link| | Main Page | Other blogs commenting on this post | 0 comments Monday, February 11, 2008 RIP, Tom Lantos and Roy Scheider. Read The Rest Scale: 4 out of 5. ADDENDUM, 6:15 p.m.: Steve Gerber, too. 25 2/11/2008 05:53:00 PM |permanent link| | Main Page | Other blogs commenting on this post | 0 comments WRITE THIS DOWN. Today: [...] On whether Obama's momentum could impact Ohio and Texas: "I don't think it does. I think those are independent electorates and everybody knew, you all knew what the likely outcome of these recent contests were and, you know, my husband didn't win any of these caucus states. You know, he didn't win Maine. He didn't win Colorado. He didn't win Washington. This is about making a strong case. You know, before Super Tuesday, you all were reporting the same thing about all of the momentum. It didn't turn out to be true. Let's have the election. You know, instead of talking about them and pontificating about or punditing about them. Let's let people actually vote, and I think in Texas and Ohio, I will do very, very well, and I intend to run very competitive winning campaigns there." Italics mine. Noting for the record. As I noted here, here is how Texas divides its delegates. Here is a more detailed explanation which makes clear that the caucuses matter greatly in getting delegates, no matter the primary vote. Formal rules here. Obama will get either a majority of delegates, or be closely competitive in Texas, I bet, and Clinton is fooling herself. Ditto in Ohio, Pennslyvania, and quite possibly in Wisconsin. Read The Rest Scale: 2 out of 5. ADDENDUM, 7:58 p.m.: Also: [...] “She has to win both Ohio and Texas comfortably, or she’s out,†said one superdelegate who has endorsed Mrs. Clinton, and who spoke on condition of anonymity to share a candid assessment. “The campaign is starting to come to terms with that.†Campaign advisers, also speaking privately in order to speak plainly, confirmed this view. I really need to overcome my depressed inertia and write up my caucus experiences, and about my awesome new elected powers. ADDENDUM, 2/12/08, 12:30 a.m.: Publius has the lengthy version. ADDENDUM, 2/12/08, 1:46 a.m.: Another explanation of Texas rules 26 here. (Via Tsam.) A much more detailed analysis. (Via Adam.) ADDENDUM, 2/12/08, 2:53 p.m.: Another analysis here and and here. 2/11/2008 05:38:00 PM |permanent link| | Main Page | Other blogs commenting on this post | 0 comments Sunday, February 10, 2008 MAYBE I SHOULD READ THE CORNER MORE OFTEN. As a rule, mostly I only read an occasional entry when someone points it out incredulously to me. I was doing that, and decided to glance at the blog generally, and immediately ran into this: Meanwhile [Kathryn Jean Lopez] Rasmussen has stopped doing Huckabee polling. 02/09 07:03 PM So I go to the link and read: [...] In the race for the Republican Presidential Nomination, Mike Huckabee had a good day on Saturday. He won the caucuses in Kansas handily, narrowly won the Louisiana Primary, and narrowly lost in Washington State’s caucuses. As a result, Rasmussen Reports will continue to track this race for the time being. Polling since Mitt Romney left the race shows John McCain with 49% of the vote, Mike Huckabee with 29%, and Ron Paul with support from 8%. Excellent reading skills. Read The Rest Scale: 1 out of 5. Incidentally, Lopez also found this part of that Rasmussen entry too uninteresting to mention, but that's utterly unsurprising: [...] This environment is obviously challenging for the Republicans, a challenge highlighted by new data showing that campaigning in the month of January was very good for the Democratic Party Brand—the number of people considering themselves to be Democrats hit a fouryear high. The entire piece was, after all, entitled: Partisan Trends Number of Democrats In Country Hits Four-Year High During First Month of Election 2008 27 It's easy to overlook that sort of thing when it's in a big headline. Trust The Corner to not quote selectively, and to get it right! + نوشته شده توسط11:13 و ساعت1387 نظر بدهید | در یکشنبه یکم اردیبهشت Amygdala From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search Brain: Amygdala corpus Latin amygdaloideum hier-219 NeuroNames Amygdala MeSH Dorlands/Elsevier c_56/12260351 III. AMYGDALA CONNECTIONS Two major bundles of fibers connect the amygdala with other areas of the brain: the stria terminalis and the ventral amygdalofugal pathway. The centromedial amygdala projects through the stria terminalis primarily to the hypothalamus and through the ventral amygdalofugal tract to the brain stem, where it can influence hormonal and somatomotor aspects of behavior & emotional states (eg, eating, drinking & sex). Projections from the lateral and central amygdala go to the lateral hypothalamus through the ventral amygdalofugal pathway. The functioning of the basolateral amygdala is more like the cerebral cortex -- with which it is closely in communication. The basolateral amygdala has direct connections (shown in the figure as bidirectional arrows) with many cerebral areas so that it can receive and modulate sensory and polysensory processing. The strongest connections are with the insular cortex, orbital cortex and the medial wall of the frontal lobe. These connections (like cortical pyramidal connections) use glutamate and/or aspartate as the neurotransmitter. Like the cerebrum, the basolateral nuclei project to the striatum (caudate nucleus, putamen and nucleus accumbens of the basal ganglia) and receives direct cholinergic (ie, acetylcholine neurotransmitter) input from the basal nucleus of Meynert. The basolateral group also projects to the mediodorsal thalamus (which 28 projects to the prefrontal cortex). Within the amygdala itself, connections primarily begin in the basolateral division and terminate in the centromedial division. Projections in the opposite direction are much weaker. It is the lateral nucleus that receives most of the sensory information arriving at the amygdala from the cerebrum. The lateral nucleus receives highly processed visual (recognition) information from the TE region of the temporal cortex. This information is projected into the magnocellular basal nucleus of the amygdala, which returns project- ions to every level of the visual information-processing hierarchy of the temporal & occipital cortex. Recordings of individual neurons in the amygdala have found neurons that respond specifically to auditory, taste, smell or somatosensory as well as visual stimuli, but the visual neurons are the most plentiful. Some amygdala neurons respond primarily to faces. In general, the lateral portion of the amygdala is regarded as inhibitory & reflective of the external environment, whereas the medial amygdala is regarded as facilitatory & reflective of the internal environment. Stimulation of the basolateral amygdala reduces feeding behavior, whereas stimulation of the corticomedial amygdala increases food intake. Stimulation of the basolateral nuclear group results in arousal and attention. Amygdala outputs tend to originate in the central nucleus, the most peptide-rich region of the brain, and are carried by peptide-containing fibers in the stria terminalis & ventral amygdalofugal pathway. There are many more projections from the amygdala to the hippocampus than in the opposite direction. The strongest projection is from the lateral nucleus to the entorhinal cortex (ie, the cortical area from which the hippocampus receives most sensory input). Secondary projections arise primarily from the parvicellular division of the basal nucleus, which receives most of the return connections (from the CA1/subiculum border zone and the entorhinal cortex). (return to contents) IV. INDICATIONS OF AMYGDALA FUNCTION 29 Monkeys without amygdalas have difficulty learning to associate a lightsignal with an electric shock -- and also have difficulty associating a neutral stimulus with a food reward. It has been suggested that the amygdala functions to associate sensation with reward or punishment. Amphetamine injections to the ventral striatum enhance the effects of a conditioned reinforcing stimulus only if the amygdala is intact. Neurons in the lateral, basal and central nuclei of primate amygdalas have been found to respond to visual stimuli associated with a food reward. But when the reward was changed to an aversive food (saline) the response of these neurons did not change -- in contrast to neurons in the orbitofrontal cortex and basal forebrain which show a rapid reversal in response to a positive reinforcement becoming a negative one. This implies that the amygdala neuron response corresponds to whether a stimulus has reward/punishment significance (and merits attention), rather than associating the stimulus with a reward or punishment. Signals from the thalamus, co-ordinated with signals from the visual cortex, evidently allow the amygdala to assist in focusing attention in response to fear [SCIENCE 300:568-569 (2003)]. Fearful images -- notably other humans with fearful facial expressions -- apparently increase attention, arousal and cortical processing through amygdala mediation. LTP (Long-Term Potentiation) can occur in amygdala brain slices. The basal nucleus has high levels of NMDA receptors. Infusion of NMDA antagonists into the amygdala blocks the acquisition, but not the expression, of conditioned fear. However, infusion of NMDA has no effect on the acquisition of conditioned taste aversion. Lesions or electrical stimulation of the amygdala impair aversion taste learning without affecting maze learning (which is dependent on the hippocampus). Conversely, lesions or electrical stimulation of the hippocampus impairs maze learning, but not taste aversion learning. Human patients with amygdala lesions show impaired immediate visual recognition, while visual memory is normal. Like the hippocampus, the amygdala is rich in receptors for cortisol (hydrocortisone, ie, stress hormone). While prolonged stress (prolonged cortisol exposure) impairs LTP in the hippocampus, the same stresses facilitate LTP in the amygdala [NEUROCHEMICAL RESEARCH 28(1):1735-1742 (2003)]. 30 Both the hippocampus and the amygdala (particularly the lateral nucleus) contain high concentrations of receptors for the benzodiazepine anti-anxiety drugs. Microinjections of benzodiazepines into the amygdala reduces fear & anxiety, but this effect is not seen upon microinjection into the hippocampus. Humans with amygdala lesions show a decrease in "emotional tension". It has been postulated that benzodiazepines may act on the lateral nucleus to prevent the linkage of emotional significance to sensory stimuli -- prior to conscious processing. Electrical stimulation of the amygdala increases plasma levels of corticosterone -- and human subjects nearly always report experiencing fear. Lesions to the cortical and centromedial nuclei markedly reduce the fearresponse of wild rats to a cat. Both the amygdala and the hippocampus contain many receptors for neurotransmitters. The central nucleus of the amygdala is the most strongly modulated: by dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine and serotonin. The basal nuclei receive moderately high inputs of dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin. There is evidence for differences in the amygdala of males & females. The posterior medial amygdala is densely populated with estrogen and androgen receptors, and this area is about 20% larger in male rats than in females. Stimulation of the corticomedial amygdala may cause ovulation in the female, but cutting the stria terminalis abolishes this effect. Lesions to rat amygdalas which include the medial nucleus eliminates male libido, but not female libido. In humans, temporal lobe epilepsy has been associated with sexual arousal in women -- and even orgasms -- but there are no reported cases of this happening for men. There may be species differences in amygdala function as well. Removal of the amygdala from female monkeys eliminate maternal behavior (resulting in infant neglect), but amygdalectomy actually increases the maternal behavior of female virgin rats (although this has been interpreted as reduced xenophobia or fear). Lesions to the amygdala of other primates disrupt social communication, but this does not occur in humans. The converse is true for lesions near Wernicke's area on the cerebral cortex -- humans are rendered verbally incoherent, but social communication of other primates is unaffected. Inputs to the human amygdala tend to be much more cognitive, whereas for other primates the inputs are more sensory. 31 Sensory inputs to the amygdala mainly terminate in the lateral nucleus. Damage to the lateral nucleus interferes with Pavlovian fear conditioning associated with specific stimuli. If an animal has been given Pavlovian fear conditioning (eg, association of a sound with an electric shock) in a distinctive environment, placing the animal in that environment can also elicit fear (contextual conditioning). Projections from the CA1 & subiculum areas of the hippocampus to the basal nucleus & accessory basal nucleus mediate contextual conditioning. Damage to these nuclei interfere with contextual conditioning. The central nucleus mediates expression of conditioned fear responses. The "defensive response" to a threatening stimulus consists of elevated heart rate (mediated by the lateral hypothalamus) and a "freeze state" (mediated by the central gray), both of which receive input from the central nucleus of the amygdala. Lesions to the lateral hypothalamus eliminate the effect on heart rate, but not the "freeze state", whereas lesions to the central gray have the opposite effect. Both responses can be evoked by amygdala stimulation. The bed nucleus of the stria terminalis mediates the release of pituitary-adrenal stress hormone (Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone, CRH) in response to fear. CRH causes the adrenal gland to release epinephrine & cortisol. Chronic stress causes cortisol-induced release of epinephrine from the locus coeruleus to the amygdala -- creating a viscious cycle. One experimenter cut the optic chiasm and forebrain commissures of monkeys after lesioning the amygdala on one side of the brain. These monkeys reacted in a wild fashion when shown threatening sights to the eye connected to the intact amygdala, but were tame when they viewed the same sights through the other eye. A monkey will normally become excited at the sight of a banana, but becomes indifferent upon bilateral amygdalectomy. Food preferences based on visual appearance are eliminated. Nonetheless, animals show no change in the motivating power of food as a reward for work, even though the animals appear to be emotionally indifferent. It has been suggested that sensory input is given emotional & motivational significance by transmission to the amygdala. Removal of both amygdalea from monkeys leads to tameness, loss of fear, "excessive" examination of objects (often with the mouth) and the eating of previously rejected foods. These symptoms are similar to those of the 32 "Kluver-Bucy syndrome" produced in monkeys by removing the anterior temporal lobe (including the amygdala), except that the Kluver-Bucy monkeys also exhibit "hypersexuality". The amygdala seems to be responsible for a kind of "food xenophobia" because rats also more readily eat unknown substances if their amygdalae are damaged. Brains of human schizophrenics show a significant reduction of the hippocampus and amygdala (especially the central and basolateral nuclei). PET scans show increased amygdala blood flow in depressed patients and in experimental subjects experiencing anticipatory anxiety prior to a mild shock. (return to contents) V. SOME INTERPRETATIONS The results of experimental science can be somewhat unsatisfying when it contains many fragmentary bits of data which have no simple explanation. But this reflects our current state of knowledge about the amygdala. The amygdala does seem to be closely associated with the feeling of fear, but removal of the amygdala seems to disinhibit feelings of lust and curiosity. Hunger and thirst are feelings centered more in the hypothalamus, whereas pure pleasure seems to be concentrated in the nucleus accumbens and the septal nuclei. Stimulation of the globus pallidus can produce an experience of joy. Interests qualify as feelings also, and are likely associated with the cingulate cortex. Guilt, anxiety and paranoia may be associated with the orbitofrontal cortex. Neurophysiology still has little to say about boredom, hope, jealousy, love and sadness, but it wouldn't surprise me if these emotions were found in different neural structures. The amygdala itself is a highly complex collection of nuclei, so it could conceivably support different emotions in different areas -- as it does appear to do in the case of fear & anger. Nonetheless, just as the processing of visual information has moved from the tectum in amphibians to the occipital lobe of species with a more developed cerebral cortex, emotional experience in humans may not have remained entirely sub-cerebral, as indicated by the right/left brain dichotomy and by the emotional effects of prefrontal lobotomy. The evidence indicates multiple centers of feeling in the brain, associated with various aspects of self (self-image, conscience, will, etc.). 33 Locating all brain functions related to feeling & self in a single "circuit" not only entails the fallacy of the homunculus, it doesn't leave much for the rest of the brain to do. This article is about part of the human brain. For the comic book character, see Amygdala (comics). Human brain viewed from the underside, with the front of the brain at the top. Amygdalae are shown in dark red. The amygdalae (Latin, also corpus amygdaloideum, singular amygdala, from Greek αμυγδαλή, amygdalē, 'almond', 'tonsil')[1] are almond-shaped groups of neurons located deep within the medial temporal lobes of the brain in complex vertebrates, including humans.[2] Shown in research to perform a primary role in the processing and memory of emotional reactions, the amygdalae are considered part of the limbic system.[3] Contents [hide] 1 Anatomical subdivisions o 1.1 Connections 2 Emotional learning 3 Memory modulation 4 Neuropsychological correlates of amygdala activity 5 See also 6 References 7 External links Anatomical subdivisions The regions described as amygdalae encompass several nuclei with distinct functional traits. Among these nuclei are the basolateral complex, the centromedial nucleus and the cortical nucleus. The basolateral complex can be further subdivided into the lateral, the basal and the accessory basal nuclei. [3][4] 34 Connections The amygdalae send impulses to the hypothalamus for important activation of the sympathetic nervous system, to the reticular nucleus for increased reflexes, to the nuclei of the trigeminal nerve and facial nerve for facial expressions of fear, and to the ventral tegmental area, locus coeruleus, and laterodorsal tegmental nucleus for activation of dopamine, norepinephrine and epinephrine.[4] Coronal section of brain through intermediate mass of third ventricle. The cortical nucleus is involved in the sense of smell and pheromoneprocessing. It receives input from the olfactory bulb and olfactory cortex. The lateral amygdalae, which send impulses to the rest of the basolateral complexes and to the centromedial nuclei, receive input from the sensory systems. The centromedial nuclei are the main outputs for the basolateral complexes, and are involved in emotional arousal in rats and cats.[4][5] Emotional learning In complex vertebrates, including humans, the amygdalae perform primary roles in the formation and storage of memories associated with emotional events. Research indicates that, during fear conditioning, sensory stimuli reach the basolateral complexes of the amygdalae, particularly the lateral nuclei, where they form associations with memories of the stimuli. The association between stimuli and the aversive events they predict may be mediated by long-term potentiation, a lingering potential for affected synapses to react more readily.[3] Memories of emotional experiences imprinted in reactions of synapses in the lateral nuclei elicit fear behavior through connections with the central nucleus of the amygdalae. The central nuclei are involved in the genesis of many fear responses, including freezing (immobility), tachycardia (rapid heartbeat), increased respiration, and stress-hormone release. Damage to the amygdalae impairs both the acquisition and expression of Pavlovian fear conditioning, a form of classical conditioning of emotional responses.[3] 35 The amygdalae are also involved in appetitive (positive) conditioning. It seems that distinct neurons respond to positive and negative stimuli, but there is no clustering of these distinct neurons into clear anatomical nuclei.[6] Different nuclei within the amygdala have different functions in appetitive conditioning.[7] Memory modulation The amygdalae also are involved in the modulation of memory consolidation. Following any learning event, the long-term memory for the event is not instantaneously formed. Rather, information regarding the event is slowly assimilated into long-term storage over time (the duration of longterm memory storage can be life-long), a process referred to as memory consolidation, until it reaches a relatively permanent state. During the consolidation period, the memory can be modulated. In particular, it appears that emotional arousal following the learning event influences the strength of the subsequent memory for that event. Greater emotional arousal following a learning event enhances a person's retention of that event. Experiments have shown [1] that administration of stress hormones to mice immediately after they learn something enhances their retention when they are tested two days later. The amygdalae, especially the basolateral nuclei, are involved in mediating the effects of emotional arousal on the strength of the memory for the event, as shown by many laboratories including that of James McGaugh. These laboratories have trained animals on a variety of learning tasks and found that drugs injected into the amygdala after training affect the animals' subsequent retention of the task. These tasks include basic classical conditioning tasks such as inhibitory avoidance, where a rat learns to associate a mild footshock with a particular compartment of an apparatus, and more complex tasks such as spatial or cued water maze, where a rat learns to swim to a platform to escape the water. If a drug that activates the amygdalae is injected into the amygdalae, the animals had better memory for the training in the task.[8] If a drug that inactivates the amygdalae is injected, the animals had impaired memory for the task. Despite the importance of the amygdalae in modulating memory consolidation, however, learning can occur without it, though such learning 36 appears to be impaired, as in fear conditioning impairments following amygdalar damage.[9] Evidence from work with humans indicates that the amygdala plays a similar role. Amygdala activity at the time of encoding information correlates with retention for that information. However, this correlation depends on the relative "emotionalness" of the information. More emotionally-arousing information increases amygdalar activity, and that activity correlates with retention.[citation needed] Neuropsychological correlates of amygdala activity Early research on primates provided explanations as to the functions of the amygdala, as well as a basis for further research. As early as 1888, rhesus monkeys with a lesioned temporal cortex (including the amygdala) were observed to have significant social and emotional deficits.[10] Heinrich Klüver and Paul Bucy later expanded upon this same observation by showing that large lesions to the anterior temporal lobe produced noticeable changes, including overreaction to all objects, hypoemotionality, loss of fear, hypersexuality, and hyperorality, a condition in which inappropriate objects are placed in the mouth. Some monkeys also displayed an inability to recognize familiar objects and would approach animate and inanimate objects indiscriminately, exhibiting a loss of fear towards the experimenters. This behavioral disorder was later named Klüver-Bucy syndrome accordingly.[11] Later studies served to focus on the amygdala specifically, as the temporal cortex encompasses a broad set of brain structures, making it difficult to find which ones specifically may have correlated with certain symptoms. Monkey mothers who had amygdala damage showed a reduction in maternal behaviors towards their infants, often physically abusing or neglecting them.[12] In 1981, researchers found that selective radio frequency lesions of the whole amygdala caused Klüver-Bucy Syndrome.[13] With advances in neuroimaging technology such as MRI, neuroscientists have made significant findings concerning the amygdala in the human brain. Consensus of data shows the amygdala has a substantial role in mental states, and is related to many psychological disorders. In a 2003 study, subjects with Borderline Personality Disorder showed significantly greater left amygdala activity than normal control subjects. Some borderline patients 37 even had difficulties classifying neutral faces or saw them as threatening.[14] In 2006, researchers observed hyperactivity in the amygdala when patients were shown threatening faces or confronted with frightening situations. Patients with more severe social phobia showed a correlation with increased response in the amygdala.[15] Similarly, depressed patients showed exaggerated left amygdala activity when interpreting emotions for all faces, and especially for fearful faces. Interestingly, this hyperactivity was normalized when patients went on antidepressants.[16] By contrast, the amygdala has been observed to relate differently in people with Bipolar Disorder. A 2003 study found that adult and adolescent bipolar patients tended to have considerably smaller amygdala volumes and somewhat smaller hippocampal volumes.[17] Many studies have focused on the connections between the amygdala and autism.[18] Studies in 2004 and 2006 showed that normal subjects exposed to images of frightened faces or faces of people from another race will show increased activity of the amygdala, even if that exposure is subliminal.[19][20] Recent research suggests that parasites, in particular toxoplasma, form cysts in the brain, often taking up residence in the amygdala. This may provide clues as to how specific parasites manipulate behavior and may contribute to the development of disorders, including paranoia.[21] See also 38