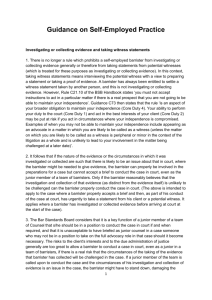

Public Access Consultation Paper – review of rule 2(i) and rule 3(1

advertisement