Stuttering Treatment in Italy

advertisement

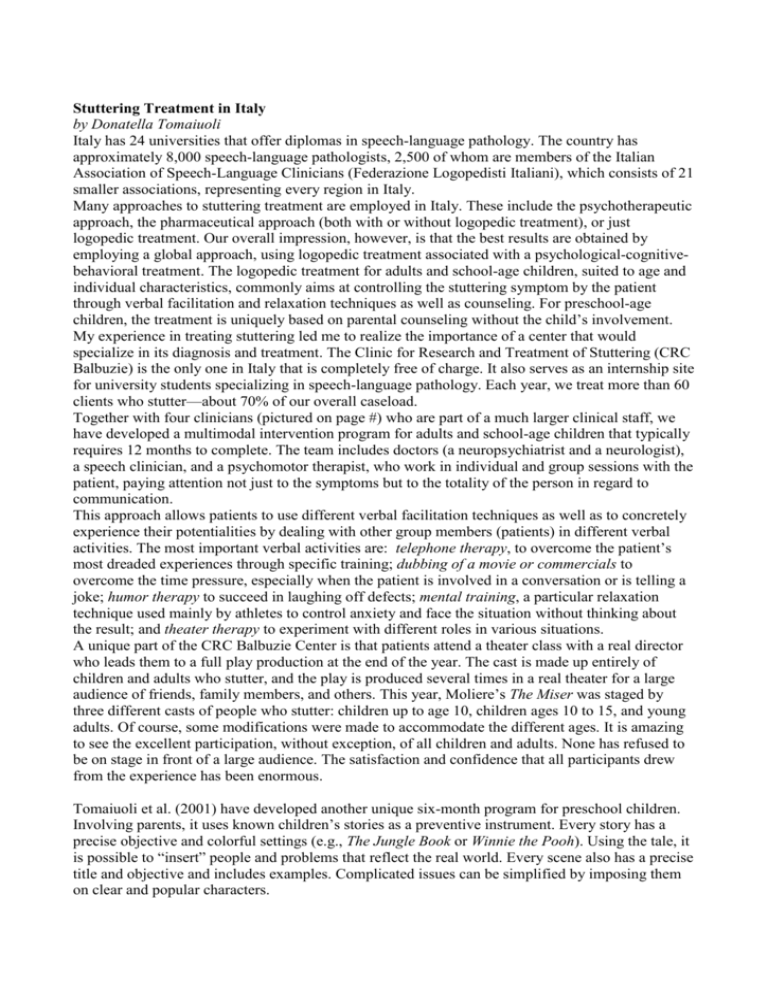

Stuttering Treatment in Italy by Donatella Tomaiuoli Italy has 24 universities that offer diplomas in speech-language pathology. The country has approximately 8,000 speech-language pathologists, 2,500 of whom are members of the Italian Association of Speech-Language Clinicians (Federazione Logopedisti Italiani), which consists of 21 smaller associations, representing every region in Italy. Many approaches to stuttering treatment are employed in Italy. These include the psychotherapeutic approach, the pharmaceutical approach (both with or without logopedic treatment), or just logopedic treatment. Our overall impression, however, is that the best results are obtained by employing a global approach, using logopedic treatment associated with a psychological-cognitivebehavioral treatment. The logopedic treatment for adults and school-age children, suited to age and individual characteristics, commonly aims at controlling the stuttering symptom by the patient through verbal facilitation and relaxation techniques as well as counseling. For preschool-age children, the treatment is uniquely based on parental counseling without the child’s involvement. My experience in treating stuttering led me to realize the importance of a center that would specialize in its diagnosis and treatment. The Clinic for Research and Treatment of Stuttering (CRC Balbuzie) is the only one in Italy that is completely free of charge. It also serves as an internship site for university students specializing in speech-language pathology. Each year, we treat more than 60 clients who stutter—about 70% of our overall caseload. Together with four clinicians (pictured on page #) who are part of a much larger clinical staff, we have developed a multimodal intervention program for adults and school-age children that typically requires 12 months to complete. The team includes doctors (a neuropsychiatrist and a neurologist), a speech clinician, and a psychomotor therapist, who work in individual and group sessions with the patient, paying attention not just to the symptoms but to the totality of the person in regard to communication. This approach allows patients to use different verbal facilitation techniques as well as to concretely experience their potentialities by dealing with other group members (patients) in different verbal activities. The most important verbal activities are: telephone therapy, to overcome the patient’s most dreaded experiences through specific training; dubbing of a movie or commercials to overcome the time pressure, especially when the patient is involved in a conversation or is telling a joke; humor therapy to succeed in laughing off defects; mental training, a particular relaxation technique used mainly by athletes to control anxiety and face the situation without thinking about the result; and theater therapy to experiment with different roles in various situations. A unique part of the CRC Balbuzie Center is that patients attend a theater class with a real director who leads them to a full play production at the end of the year. The cast is made up entirely of children and adults who stutter, and the play is produced several times in a real theater for a large audience of friends, family members, and others. This year, Moliere’s The Miser was staged by three different casts of people who stutter: children up to age 10, children ages 10 to 15, and young adults. Of course, some modifications were made to accommodate the different ages. It is amazing to see the excellent participation, without exception, of all children and adults. None has refused to be on stage in front of a large audience. The satisfaction and confidence that all participants drew from the experience has been enormous. Tomaiuoli et al. (2001) have developed another unique six-month program for preschool children. Involving parents, it uses known children’s stories as a preventive instrument. Every story has a precise objective and colorful settings (e.g., The Jungle Book or Winnie the Pooh). Using the tale, it is possible to “insert” people and problems that reflect the real world. Every scene also has a precise title and objective and includes examples. Complicated issues can be simplified by imposing them on clear and popular characters. For example, Jack Panther and the Woodland Friends are employed to work on interpersonal relationships or assertiveness training. In the first scene, Jack, who lives in the forest, loses his friends. All, including him, escaped the big fire and move to different forests. Jack, now alone in a new forest, must make new friends and be accepted into a new group. He must experiment with various approaches, including performing roles he does not like, to finally succeed. Skittle, the baby elephant, is used to work on reducing fear of others’ judgment. In the last scene, Skittle experiences difficulties with precise movement because of his size and is often clumsy in the presence of friends. Negative judgments by others make him shy and produce inferiority feeling. To change the situation, he will try to show other aspects of his personality, as well as overcome his handicap, transforming it to a point of strength. In this way the child finds himself in a near-real world that is less intimidating than his real world. The child is instructed to act in different roles within the same tale. The clinician also actively participates, playing a role that either facilitates or hinders communication. Additionally, family members become involved. Whereas early in the program they serve primarily as spectators, later they become active participants, taking several roles that allow assertiveness training. In this phase, the clinician becomes an important verbal and behavioral model for the parents. In my view, the different tales allow children to play and interact with different personalities, and through these they realize what the optimal behavior is, including assertiveness, to achieve the objective. The child also realizes the importance of non-verbal communication, learns to identify basic elements of the verbal communication (voice tone, accentuation, rhythm, and pauses), and experiences the reinforcement of communication (handshakes, cheers, embraces). Thus, although the program does not attempt to deal directly with stuttered speech, it is aimed at helping the child cope better with the stuttering problem, improve self-awareness, adjust, and function well in school and society. Such gains eventually also result in a significant reduction in dysfluency. Some results have been reported by us (Tomaiuoli et al., 2001; also summarized in Yairi & Ambrose, 2005). Finally, in the past seven years two international conferences on stuttering were organized in Rome. The CRC Balbuzie, in cooperation with “La Sapienza” University, is now planning another conference to be held in Rome in May of 2007. Donatella Tomaiuoli is a psychopedagogist and SLP specializing in stuttering. She is the director of the Clinic for Research and Treatment of Stuttering (CRC Balbuzie), Rome, and a professor in the Department of Speech Therapy, La Sapienza University, Rome. She developed a multimodal intervention program for adults and school-age children who stutter and a preventive “play” program for pre-school-age children. Contact her at crc.balbuzie@tiscali.it. Sidebar References Tomaiuoli, D., Del Gado, A, Lucchini, E., Lattuca, S., Spinetti, M. (2001). The fantastic world of the tales. Presented at the Second International Symposium on Stuttering. Rome, Italy. Yairi, E. & Ambrose, N. (2005). Early childhood stuttering. Austin, TX: Pro Ed.