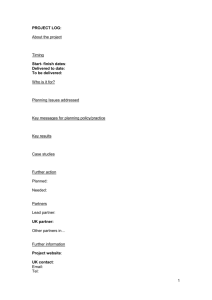

Chapter 9 - One.Tel's Financial Circumstances at

advertisement