Pericles - CarnoGold

advertisement

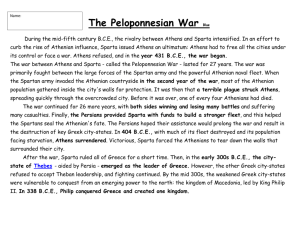

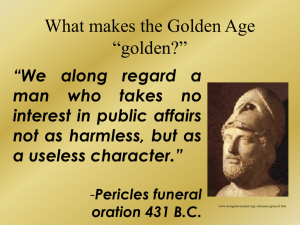

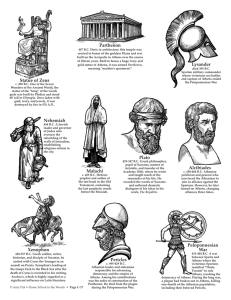

Pericles We call it the "Golden Age"—the period during the 5th century B.C. when the Greek city-state of Athens experienced a cultural flowering of extraordinary power and importance for Western culture. It is a period that still calls to us, still echoes, as we read the plays of Aeschylus, Sophocles, or Euripides; gaze at architectural wonders like the Parthenon; consider the wisdom passed down from Socrates and Plato; or, perhaps most of all, consider the origins of our own democracy. The Age of Pericles uses the career of the leading Athenian politician and general from c. 450–429 B.C. as a prism through which to view this brief but remarkable era, and to ask why that echo has persisted for so long. In the generation that followed Pericles’s appearance on the public stage shortly after the Persian wars, Athens rapidly transformed the alliance of Greek states—an alliance first created as a defense against the Persians—into a true Aegean empire, dominated by the Athenians and their mighty navy. But this dramatic increase in military power, cultural influence, and prestige was also accompanied by something unique: the growth of full participatory democracy. This course examines the daily workings of that democracy and the whole of Athenian culture, including: how Athenians were trained for citizenship what Athenian democracy actually meant in practice the profound role of religion in Athenian life. Were there Stains on the "Golden Age"? But in examining the lives of Athenian men and women, this course also confronts aspects of the "Golden Age" whose echoes are far less glorious. It asks, for example, what freedom and autonomy really meant to a society that relied on slaves and was ruthless in its treatment of its subjects. To answer this and other questions, the course constantly juxtaposes the striking accomplishments of Athenian culture in such fields as philosophy, tragedy, comedy, sculpture, and architecture with its equally striking flaws, including: the exclusion of women from public life Athenian reliance on slavery, including the abuse of those slaves the cruel treatment of other Greek populations. In following Athens from the height of its power to its defeat at the hands of the far different Greek city-state of Sparta, these lectures produce a portrait of a complex people and a complicated culture whose ties to our own civilization are not casual, but deeply meaningful. The Living Dialogue that is History Gandhi was once asked what he thought of Western civilization, notes Professor Jeremy McInerney. He replied that he thought it would be a ‘good idea.’ "In the world after September 11, we have come to realize that there are those who loathe and despise everything Western," says Professor McInerney. "If that is so, then it is worth asking, ‘What is valuable in Western culture?’ "The Greeks demand that we learn about our own history, the roots that connect us to the past, the avenues by which the past has become the present. If our culture has real meaning, and if notions of justice, freedom, and equality are to be a reality, then we cannot live in a vacuum in which history is forgotten. We have to be aware of the past and engage with the living dialogue that is history." The "Right" of Freedom? As he leads you through daily life in Athens, Professor McInerney not only weaves in the underlying beliefs that drove those daily events, but also draws analogies with contemporary ideas and events to reveal how we are both like and unlike those ancient Athenians. He reveals, for example, the origins of British common law in the archives of Athens as he explores some of the legal testimony left behind by the Athenians. He also compares our conception of the term freedom with what the Greeks understood it to be, including the role of their stunning victory over the Persians in helping to amplify that understanding. And if you are surprised to learn that the ancient Athenians— whom so many of us idealize as the spotless source of our ideas about democracy—considered freedom to be simply a status, and not a right at all, you’ll likely be even more surprised to learn what comes next, for one of the Athenians’ most important philosophical justifications for slavery was penned by, of all people, Aristotle. Equally troubling to our contemporary ears, though hardly unexpected in the ancient world, was the position occupied by women, no matter how high on the social ladder. Much of that becomes clear in Professor McInerney’s argument that Aspasia, the long-term mistress of Pericles—what we would consider his common-law wife—and mother of his son, was never a prostitute, as her origins are commonly portrayed. Dr. McInerney uses the famous case of a woman named Neaera to show how many different forces (particularly the concerns of property and citizenship, including Pericles’s own role in redefining the latter) combined to sharply limit the role of women in ancient Athens. One of the most striking examples of that came in the famous funeral oration given by Pericles to honor the fallen of the first year of the Peloponnesian War against Sparta. In an address otherwise remembered as an expression of the ideal of moderation—and perhaps the closest thing we have to a statement of the ideology of classical Athens—Pericles also reveals that for Athenian men, a public image was a source of pride, while for women such an image was cause for shame, as it went against the idea that women should be only in the background. A Window on Ancient Athens This well-rounded portrait of almost every aspect of Athenian life during the Golden Age includes: The different ways Athens and Sparta raised their children. Including the Spartan practice of giving girls only the lightest of garments, the idea being to inure them to the cold to make them healthy and vigorous enough to raise the next generation of Spartans. The fate of Athenian girls as mothers and managers of the household. Their figures on pottery have lighter skin— evidence of a life properly spent indoors—while Athenian boys received an intensely rich education. Young Pericles's role in bringing Aeschylus’s masterpiece, The Persians, to the stage, what it meant to his own career, and what it said about the obligations of the very rich in Athens Why did Spartans reject the aid of Athens in putting down a slave revolt? The public humiliation over the rejection later led to the 10-year banishment of Cimon, the leading politician in Athens. Solon, the Athenian lawgiver, introduced reforms including an important shift to wealth—which could be acquired—rather than birth as the determining factor of one’s place in Athenian society. Examining Thucydides’s terrifying description of the Plague’s physical and social impact on Athens—including the death of Pericles—and its possible role in the ultimate defeat of Athens by Sparta. Athenians organized their busy lives around two distinct calendars, secular and religious; discover the Panathenaea, an extraordinary festival and procession that honored Athena. As one scholar has described that special day, "The city would have been resounding to the bellowing of cattle being dragged off to their slaughter. The acropolis, by the end of the day, would have been drenched in blood, flowing all over the rock, from the animals that had had their throats cut." An Obsession with Property The Athenians were obsessed with protecting the value of a family’s property, and laws about marriage and inheritance created constant legal manoeuvring. Professor McInerney outlines the detailed record of a legal case that gives us a glimpse of the actual property and real goods of a well-to-do Athenian family, and the role of slavery in sustaining those families in their wealth. He also describes Greek ideas about death and the way to honor both ordinary citizens and fallen heroes, including mourning processions that became so overwhelming that laws had to be passed to limit their size and cost; terracotta tubes leading into a burial mound to permit blood libations to be offered to the spirits; and the possibility that the bones brought back to Athens by Cimon—which he claimed to be those of Theseus, slayer of the Minotaur—might have been those of a dinosaur. Art in the Age of Pericles You examine the details of how some of the greatest plays of the Athenian stage were brought to life, such as: Prometheus hurling defiance at the gods after giving fire to mankind in Aeschylus’s Prometheus Bound the surprising interpretation Professor McInerney gives to Euripides’s Medea, revealing deeper meanings than those of the traditional reading of "Hell hath no fury" the vigour and openness of Athenian comedy, in which no subject and no person, no matter how powerful, was above criticism and the most pointed satire imaginable. A "Complex, Complicated Civilization" The Age of Pericles tells the story of a time and people to whom we are inextricably bound. As Professor McInerney notes, "the Greeks established democracy, valued the rule of law, and articulated definitions of freedom and virtue. At the same time they owned slaves, denied women a public voice, and asserted their racial superiority. "They were a complex, complicated civilization, and we are their descendants. These lectures examine that relationship, exploring much that was good and bad in the Golden Age of Pericles. By engaging with the Greeks, we may come to understand our own world more fully."