NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit

advertisement

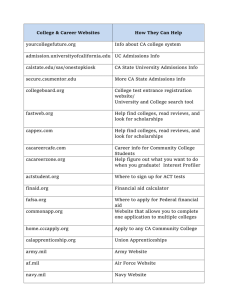

NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes Purpose: To improve safety across the NAVSEA Industrial Activities and drive safety hazards and mishaps to “As Low as Reasonably Achievable.” Location: Washington, DC Date: May 11 – 13, 2010. Enclosures: (1) Meeting Agenda (2) Attendance Roster (3) Bibliography Action Items: 1. Publish Meeting Minutes and a Plan of Action and Milestones for the NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit. Action: SEA 04R (Mr. Brice). Due: May21, 2010. 2. Add Supervisors of Shipbuilding, Conversion, and Repair to the Trouble Report distribution list. Action: SEA 04XQ (Mr. Mieszczanski). Due: May 21, 2010. 3. Contact the Naval Safety Center to discuss NAVSEA’s intention to complete a Trouble Report and a critique for a fatality in advance of the SIR. Action: SEA 00L (Ms. Zivnuska). Due: June 30, 2010. 4. Contact the fleet concerning how NAVSEA can provide input to the JFFM. Action: SEA 04RS (CDR Gelker). Due June 30, 2010. 5. Contact the fleet and the Naval Safety Center concerning addressing ship’s force unsafe practices not related to ship availability. Action: SEA 04RS (CDR Gelker). Due June 30, 2010. Key Points The Nuclear Navy’s Industrial Principles permeated the remarks of Troy Mueller (NAVSEA 08R): rising standards of excellence, technical self-sufficiency, facing facts, training, total responsibility, and capacity to learn from experience. A keystone principle of the Naval Reactors safety management approach is to “work hard on small problems today so that you don’t have to deal with big problems later.” 1 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes An underlying theme of many mishaps was that the people involved had either lost or never acquired the ability to “see” correctly, that is, to proactively identify deficiencies and precursors of mishaps, to address them, and to reduce the likelihood of mishaps occurring. The “safety” triangle and hierarchy of problems (number and severity) model the experience of accident investigators that most incidents and serious problems do not strike like a “bolt from the blue,” completely unexpected and hard to anticipate. On the contrary, [major problems or disasters] are typically preceded by a [large] number of [smaller] problems … that an organization has been tolerating for some time. By identifying, reducing and aggressively investigating 3rd order deficiencies, organizations “put pressure” on the triangle and push more problems lower (or prevent them in the first place) and build a broad population of questioning attitudes and awareness of deficiencies that will ultimately reduce the likelihood of 1st order incidents. Working hard on the small problems today through persistent questioning to determine why things did not go as planned enables members of the organization to remain vigilant and “see” the deficiencies that exist (Karl Weick calls this “preoccupation with failure” and “mindfulness”). [We need] two shifts in mindset: (1) going beyond the minimal requirements of the regulation (similar to VPP), and (2) to be really serious about something, it has to be personal, you have to have something meaningful to you at stake. High Risk Work Permits [used by Naval Reactors at their facilities] … [require] both a worker and his manager [to sign] that the high-risk work is warranted, that the formal work procedure has been engineered to provide necessary hazard mitigation to protect workers, that the workers are adequately trained, that the workers will be briefed before performing the high-risk work, and that arrangements have been made to provide field surveillance during the high-risk work. The High Risk Work Permit forces everyone concerned with the work to acknowledge that they cannot think of a better way of doing this work (guaranteed to make engineers uncomfortable), a very important source of “cognitive dissonance” that was a key to changing their approach A key lesson learned from the High-Risk Work Permit initiative is to spend more time on getting organizational buy-in for the approach as opposed to implementing them by … the “shock and awe” approach… people would have spent less time resisting the changes if they had understood what [NR] was trying to accomplish earlier. If achieving minimum requirements only is the accepted practice, then normal variability around the mean due to human performance factors will result in a 50% failure rate (i.e., the minimum standard is not achieved 50% of the time). As a result, a higher standard of excellence must be set to achieve a margin to minimum requirements. DuPont Route to ZERO (Injuries) model … has four levels, depicted as a progression that characterize the kinds of thinking that lead to improved safety performance. Level 1 is 2 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes Reactive – Survival Of The Fittest. Level 4 is Interdependent – We Are Responsible For the Safety Of Each Other (what the Navy calls “watch team back up”). VADM McCOy: “a problem well-defined is half-solved.” A shipyard can have accident-free days and go right to a pinnacle event because managers do not fully understand how the work is being accomplished. it [is] a mistake to focus on process first. Focus on people, their training, and their capability to do the work first. People who do not think with good engineering discipline write bad self assessments The group determined to assign four working groups, one from each shipyard to address one of the four high-risk areas, to address risk management and worker commitment to safety: 1. 2. 3. 4. PNSY (Code 950 2730/270), Electrical Safety. NNSY (Code 970 980/710), Fall Protection. PSNS&IMF (Code 920/250), Confined Space Entry. PHNSY&IMF (Code 960 2350/260), Energy Control/Lock Out – Tag Out (LOTO). Meeting Minutes Discussion Topics: Tuesday, May 11, 2010 Welcome and Opening Remarks (RADM Campbell). RADM Joseph Campbell, Deputy Commander, Logistics, Maintenance and Industrial Operations (SEA 04), opened the Safety Summit by welcoming the participants and reviewing his expectations for the meeting. He discussed his Four S guiding principles with the group – Service, Safety, Success, and Satisfaction. Service is why we exist (to provide Fleet Readiness), Safety is foremost and essential to mission success, Success equates to meeting cost, schedule, and quality standards, and Satisfaction is the cornerstone of employee morale and motivation. RADM Campbell challenged the group to improve safety dramatically in the Navy’s ship repair and maintenance business. RADM Campbell participated in the Summit through noon, and attended the out brief on Thursday morning. Opening Presentation (Mr. Brice). Mr. James Brice, Assistant Deputy Commander for Maintenance, Modernization, Environment/Safety (SEA 04R), opened the Safety Summit by presenting the meeting objectives and deliverables and a review of current safety performance in the Navy’s ship repair and maintenance business (i.e., Naval Shipyards, Regional Maintenance Centers, and Supervisors of Shipbuilding, Conversion, and Repair). He reviewed three recent, serious safety mishaps (fatality at NNSY from an engineer falling off a roof, the electrocution of a Navy Chief on CVN 76, and an arc flash caused by a Pearl 3 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes Harbor electrician that violated electrical safety rules with a non-approved tool working in the battery well of the USS CHEYENNE). He described Navy leadership concerns in the wake of these mishaps. Navy leadership concluded that the ship repair and maintenance business must (1) adopt a risk-based approach to safety by focusing on reducing hazards and the potential for serious injuries; (2) find and fix safety problems instead of them finding us; (3) take on a long-range vision of zero injuries; and (4) embrace and adopt proven Navy safety models (e.g., Nuclear Safety, Radiological Safety, and Crane Safety). He reviewed the Safety Pyramid (focusing and following up on lower level issues before they lead to bigger problems) and the As Low As Reasonably Achievable (ALARA) approaches to risk management. Given that two unrelated fatalities have recently occurred in the Navy’s ship repair and maintenance business, NAVSEA currently is defining its pinnacle safety event (i.e., the event that could shut down or seriously impact the business) as a single mishap involving multiple fatalities. The objective is to push the top of the pyramid (the pinnacle events) “down” over time by improving standards of work and safety performance so that the pinnacle event begins a transition to a single fatality, then a serious injury, then a minor injury, or As Low As Reasonably Achievable. He reviewed DuPont’s Route to Zero model for human behavior related to accidents and safety, which essentially posits that organizations become more safe and efficient when they transition from reactive approaches to safety (only taking actions after an accident) to interdependence among workers, work teams, and management such that an organization’s safety performance is a matter of pride for its workforce. Mr Brice also reviewed what he called the Voluntary Protection Program (VPP)+ concept, taking what is already working with the VPP currently embraced by many NAVSEA activities and taking some specific steps to improve the relationship between increased safety, quality performance, and increased worker productivity and efficiency. He concluded by reviewing the detailed agenda for the Safety Summit and reviewing NAVSEA leaders’ expectations for the meeting. Refer to Enclosure (1), Meeting Agenda for details. Mr. Brice challenged attendees to develop creative ways to achieve a culture change and get everyone’s commitment to safety. Refer to Enclosure (2), Attendance Roster. Safety Principles (Mr. Mueller). Mr. Troy Mueller, Naval Reactors (SEA 08R), explained the safety principles employed by SEA 08 to manage safety in the five joint DON/DOE facilities supporting the U.S. Naval Nuclear Propulsion Program (i.e., Knolls, Kesselring, Bettis, etc.). [Soule note: the Nuclear Navy’s Industrial Principles permeate these remarks. Briefly, they are: rising standards of excellence, technical self-sufficiency, facing facts, training, total responsibility, and capacity to learn from experience. For more information, see enclosure (4)] A keystone principle of the Naval Reactors safety management approach is “to work hard on small problems today so that you don’t have to deal with big problems later.” Mr. Mueller’s experience is also informed through participating in a number of mishap investigations, including collisions and groundings of submarines and mishandling of nuclear 4 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes weapons. An underlying theme to these mishaps was that the people involved had either lost or never acquired the ability to “see” correctly, that is, to proactively identify deficiencies and precursors of mishaps, to address them, and to reduce the likelihood of mishaps occurring. By way of setting context, Mr. Mueller reviewed how SEA 08 uses the safety pyramid in the nuclear propulsion radiological exposure controls (Figure 1. Safety Pyramid). Overexposure to radiation is what the Radiological Controls group at Naval Reactors defines as their pinnacle event. The Safety Pyramid is subdivided by three horizontal lines parallel to the base of the triangle. Level 1 problems, what NAVSEA 08 calls “incidents” are in the top section of the triangle with Levels 2 through 4 below that. Naval Reactors requires that Level 1 problems get reported to the Director Of Navy Nuclear Power in writing. These reports get a lot of review and will, by the nature of the interaction with Naval Reactors before and after they are sent, require the engagement of an organization’s senior leadership to understand the problems and be accountable for corrective action (thus driving future improvement because of their engagement with the details). SEA 08 has defined 17 items that constitute a prioritized list of Level 1 incidents, with overexposure being number one. SEA 08 has modified the criteria for incidents over time as organizations have improved to ensure the standard is consistently improving. This approach to improving the standard minimizes the tendency for organizations to become complacent about their performance and ensures there is a steady flow of problems for organizations to work. Level 2 problems are near misses (i.e., nearly incidents) that should be prosecuted by an organization the same way they would a Level 1 problem without the requirement to send a report to NAVSEA. Mr. Mueller characterized near misses as “gifts” because they provide the organization an opportunity to learn from them without causing any damage or injuries. The facilities define what constitutes a near miss. The facilities conduct critiques or appropriate level of fact finding on all Level 1 and 2 items. Level 3 and 4 deficiencies are deviations from standards that did not cause a significant event to occur. However, a trend in or series of lower level deficiencies can constitute a near miss and should be evaluated for a critique to learn lessons to arrest the trend. The triangle and hierarchy of problems (number and severity) model the experience of accident investigators that most incidents and serious problems do not strike like a “bolt from the blue,” completely unexpected and hard to anticipate. On the contrary, 1st order problems are typically preceded by a number of 2nd order problems and an even larger number of 3rd order problems that an organization has been tolerating for some time. In almost every case of an organizational accident like the loss of a Space Shuttle, the organization was tolerating and not correcting many 3rd order deficiencies. By identifying, reducing and aggressively investigating 3rd order deficiencies, organizations “put pressure” on the triangle and push more problems lower (or prevent them in the first place) and build a broad population of questioning attitudes and awareness of deficiencies that will ultimately reduce the likelihood of 1st order incidents. In this way, organizations can look closely at how they accomplish work and attempt to design processes to make second and first order problems exceedingly 5 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes Severity unlikely. The standard of performance is the same every day. Over time, there may be some variance in the number of critiques and problems experienced, but this tends to flatten (depicted as a sine wave in Figure 1) when these concepts are consistently practiced. This proactive approach of working hard on the small problems today through persistent questioning to determine why things did not go as planned enables members of the organization to remain vigilant and “see” the deficiencies that exist Number of Uncorrected Deficiencies (Karl Weick calls this “preoccupation with failure”). This proactive approach also is a form Figure 1. Safety Pyramid of continuous improvement (i.e., number of occurrences and severity of incidents, problems, and deficiencies shrinks). Everyone can share in Troy Mueller’s philosophy that “I reserve the right to be smarter tomorrow than I am today.” [Soule – this means one should continually try to improve one’s knowledge and learn from experience/others to be better tomorrow than today.] For more information on these High Reliability Organization practices, consult “Managing the Unexpected,” Weick and Sutcliff, “Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents,” Reason, and “Managing Maintenance Error,” Reason and Hobbs. Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 Lessons Learned (Mr. Mueller). Mr. Mueller reviewed lessons learned from SEA 08’s experience with Environment, Safety, and Health (ESH) oversight of the joint DON/DOE facilities. In the facilities, ESH inspections are combined with Radiological Control (RADCON) inspections since Mr. Mueller is responsible for both. Mr. Mueller discussed the differences between ESH and RADCON standards. In either case, the worker is exposed to hazards; the objective is to keep the worker safe and never take unnecessary risk. Safety has overtaken RADCON in terms of his current focus. SEA 08 conducted a safety summit of the DOE facilities and accomplished two objectives: (1) Definition of pinnacle event (i.e., What kind of problem could occur for which you would turn your badge (i.e., resign)?). (2) Definition of 1st order incident reporting criteria (i.e., fatality, injuries, near misses) for safety problems. The facilities set the pinnacle event to multiple fatalities initially, then subsequently changed the pinnacle event to a single fatality. The facilities identified 17 types of incidents requiring a critique. Prior to implementing this proactive approach, the facilities reported 10 to 15 incident reports a year. After adopting the new standards, each site issued 15 incident reports in two months, with many incidents identified by government representatives at the sites instead of the organization identifying them on their own. Underlying this approach are two shifts in mindset: (1) going beyond the minimal 6 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes requirements of the regulation (similar to VPP), and (2) to be really serious about something, it has to be personal, you have to have something meaningful to you (like your job) at stake. to improve your performance. High Risk Work Permits (Mr. Mueller). Mr. Mueller discussed the High Risk Work Permit recently introduced at SEA08 facilities. SEA 08 and the DON/DOE facilities defined what constituted high-risk work and a permitting process to perform high-risk work. Prior to implementing a High Risk Work Permit, many facilities managers were unaware of high-risk work being conducted in their facilities on a weekly basis. Appropriate engineering involvement was also absent in the High Risk work. The High Risk Work Permit corrected this condition by requiring both a worker and his manager’s signature authorization to perform the work. In signing the permit, the two affirm that the high-risk work is warranted, that the formal work procedure has been engineered to provide necessary hazard mitigation to protect workers, that the workers are adequately trained, that the workers will be briefed before performing the high-risk work, and that arrangements have been made to provide field surveillance during the high-risk work. The High Risk Work Permit also requires the engineer preparing the work procedure, the engineer’s supervisor, the safety organization, and the manager responsible for performing the high-risk work to sign a statement concurring with the work procedures developed to perform the high-risk work, including the hazard mitigation strategy to perform the work safely. The High Risk Work Permit includes a job briefing sign-off sheet for the workers performing the work. In essence, the High Risk Work Permit forces everyone concerned with the work to acknowledge that they cannot think of a better way of doing this work (guaranteed to make engineers uncomfortable). The process challenges the engineers and their managers to engineer the hazards out of high risk work to the maximum extent practicable (Soule – engineers hate to have to say that they cannot think of a better way to engineer work, a very important source of “cognitive dissonance” that was a key to changing their approach). In the first year of implementation, the facilities issued lots of High-Risk Work Permits. After three years, the facilities now issue one-tenth of the number previously issued. The managers changed their mindset to approaching the work and now engineer the work more safety and efficiently. Improved safety leads to improved worker efficiency and morale. A member of the audience asked for the return on investment from implementing improved engineering controls. Mr. Weishar (Naval Reactors) related an example of a facility installing scaffolding around a component. The scaffolding eliminated the need for the workers to wear fall protection equipment and required less time and fewer workers to complete the job (i.e., better planning and execution, improved efficiency). The return on investment also comes through the number of manyears saved from reduction of injuries and days away from work and the expenses associated with processing medical claims. Mr. Mueller said that a key lesson learned from the HighRisk Work Permit initiative is to spend more time on getting organizational buy-in for the 7 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes Mean Excellence Margin to Failure Standards approach as opposed to implementing them by management fiat (what he called the “shock and awe” approach). He believes that people would have spent less time resisting the changes if they had understood what he was trying to accomplish earlier. Minimum Requirements As Low As Reasonably Achievable (Mr. Mueller). Mr. Mueller elaborated on the ALARA concept. In radiological protection, a key objective is to keep the risk to workers of People cancer from radiation to a level lower than risks Figure 2. Margin to Failure encountered in everyday life (like driving a car or smoking). Workers generally accept the risk out of a patriotic duty they feel from service to their country. There is a benefit to our country from workers accepting this risk. SEA 08 has an unwritten contract with the workers to not expose them to unnecessary radiation. Unnecessary, wasted exposure is unacceptable. The correlation to safety is the concept of wasted risk. Mr. Mueller encouraged the group to look at safety risk differently than they have in the past (“it’s a cost of doing business), and to attack it differently. He encouraged the group to work on lower-level problems as a means of preventing higher-level incidents from occurring (Figure 1. Safety Pyramid). In the wake of the recent NNSY fatality, SEA 08 looked at safety during its most recently scheduled audit. SEA 08 auditors saw lots of safety risk at NNSY. As one example of wasted risk, six workers (with equipment) were found to be working on light-duty scaffolding, rated for only three workers. Another example was a lack of painted walkways with no place to walk. Dodging fork trucks driven by operators talking on cell phones (as Mr. Mueller had to do) is wasted risk. Wasted risk equals unnecessary risk. A key question is, “What are the best criteria for ALARA in safety?” The group addressed this question over the course of the summit meeting. Minimum Requirements Mentality (Mr. Mueller). Mr. Mueller addressed the need to exceed minimum requirements in safety so as to create a margin for failure to compensate for human performance factors (Figure 2. Margin to Failure). If achieving minimum requirements only is the accepted practice, then normal variability around the mean due to human performance factors will result in a 50% failure rate (i.e., the minimum standard is not achieved 50% of the time). As a result, a higher standard of excellence must be set to achieve a margin to minimum requirements. Another outcome of achieving minimum requirements only is rework (Figure 3. Rework). A higher standard of excellence must be set to achieve peak efficiency of workers and to minimize rework. However, a point can be reached when worker efficiency begins to drop as a result of investing in more controls than are necessary. 8 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes Excellence Efficiency Minimum Requirements Mr. Mueller said he does not believe the Mean of Investing Workers in more shipyards currently have enough controls than engineering controls in place for the work necessary they do. He said that systemic issues line up like switches in a circuit to close and create a failure even in the most unlikely Rework situations. The last switch is the easiest issue to find and address. He questioned why the shipyards spend so much time critiquing the last switch. He cautioned against blaming the worker for the failure. Standards The value of the critique is identifying the Figure 3. Rework preceding switches that should also be worked. He reiterated his sense that the shipyards do not have enough controls (actions that tend to keep switches “open”) in place (i.e., engineering controls). Mr. Mueller also expressed concern about implementing 17 1st order criteria at the same time since people may find the problems they identify overwhelming, given the likely population in each criterion. He recommended gradually increasing the standards associated with the criteria; otherwise, it could create a shock to the system. He recommended spending more time teaching people how to see the problems in front of them every day. Route to Zero (Mr. Mueller). Mr. Mueller discussed the DuPont Route to ZERO (Injuries) model. The model has four levels, depicted as a progression that characterize the kinds of thinking that lead to improved safety performance. Level 1 is Reactive – Survival Of The Fittest. Level 2 is Dependent – My Supervisor Is Responsible For My Safety. This level relies on fear and discipline. Level 3 is Independent – I Am Responsible For My Safety. This level aims to train the workers to be responsible for their own safety [Soule – this should be familiar to anyone involved in the Navy Nuclear Power Program]. Level 4 is Interdependent – We Are Responsible For the Safety Of Each Other (what the Navy calls “watch team back up”). Each of these levels is present in the Navy ship repair and maintenance business, with the mean behavior probably resting on Level 2 (Dependent). The group noted that critiques often blame the worker for the failure. An objective is to create a culture of openness, with no fear of reprisal for bringing up uncomfortable, but accurate, information in critques and fact finding meetings. In “Managing the Risks of Organizational Failure,” James Reason identified four sub-cultures necessary to support a Safety Culture: a Reporting Culture, a Just Culture, a Flexible Culture, and a Learning Culture. Mr. Mueller discussed the concept of a Just Culture. A just culture protects people’s honest mistakes from being seen as culpable. The goal is interdependence, or actively caring for the people around you. The group discussed whether the Route to ZERO model is a series progression 9 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes (does an organization have to pass through each of the stages?). DuPont might say it is a progression because DuPont passed through each progression in developing the model. However, because industry learned DuPont’s lessons, it may be possible to work on achieving Interdependence without going through all of the progressions [Soule – this seems terribly naïve. Workers are not just going to “get it” because you explain something well to them or show them a fancy diagram. They have to internalize new ways of thinking and behaviors so it would seem very unrealistic to think an organization could be composed of some advanced form of human that could skip stages in this developmental process for their thinking.]. Mr. Mueller recommended cultivating openness of workers in critiques. He talked about the pilot project SEA08 has undertaken with conducting worker-led critiques, with assistance from a facilitator, followed by a management summary meeting. This approach would empower the workforce to own the problems identified. Mr. Mueller also recommended cultivating a Reporting Culture. There is value in writing down problems and reporting them, both personally and organizationally. Problems that are written down are more likely to be fixed. Mr. Mueller recommended several books to the group that present insights discussed herein. Refer to Enclosure (3), Bibliography. NAVSEA Leadership Perspective (VADM McCoy). VADM Kevin McCoy, Commander, Naval Sea Systems Command (SEA 00), gave the group his perspective on improving safety performance in the Navy’s ship repair and maintenance business. He said that he is very concerned about safety performance. Current performance is unsatisfactory, with two fatalities occurring in the past year. The investigation of the first fatality at Norfolk Naval Shipyard indicated that managers do not understand what is happening on the deck plates. The investigation of the second fatality in USS RONALD REAGAN (CVN 76) indicated neglect on the part of shipyard workers to prevent the fatality of a Sailor. The Voluntary Protection Program has focused lots of attention on small things to reduce injury rates, yet the corporation has experienced two pinnacle events in a brief time frame. VPP principles have not penetrated the culture or they may be insufficiently understood and practiced. NAVSEA leadership will accept some number of strains and sprains, but industrial activities must prevent pinnacle events. The investigation of the arc flash mishap in USS CHEYENNE (SSN 773) documented that the worker received a job briefing before starting the job. This fact raises the question, “What was in the job briefing?” The chain of events leading to more serious incidents is happening every day. By luck, a switch is open, thereby preventing a life-altering event from occurring. Lower-level indicators in safety are not being monitored to prevent the more serious incidents. VADM McCoy asked the group to take extra time to define the problems they see well. He believes that a problem well-defined is half-solved. He asked the group to consider a series of questions: What is the problem? Have we become safety-blind because of the risks we are routinely accepting? How are we really going to manage risk? What messages are we sending? How is life going to be different after this 10 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes meeting? High risk events need to be identified and managed. Managers must know how the work is being done. The group discussed various aspects of the problem, in both the public- and private sector shipyards. He agreed that the Program Executive Officers (PEOs) are not looking at safety. He agreed that the RMCs have been neglected. However, VADM McCoy questioned whether the problem has been properly defined. He noted that a shipyard can have accident-free days and go right to a pinnacle event because managers do not fully understand how the work is being accomplished. There are two at-risk groups in the workforce – the least experienced workers and the most experienced workers. He advised the group to pick a reasonable number of things to work on, figure out what to do differently, and go and do. He said that we are flying blind because we don’t track the precursors to pinnacle events. He suggested that we do not know what the problem is because we do not have the knowledge base. Mainstreaming Safety (Mr. Brice). After lunch, Mr. Brice reviewed key points from the morning’s discussions: 1. It is personal – compared to RADCON, have a long way to go 2. Leaders set the example – need a communication plan 3. Learn how to see – ownership aspect 4. Define the problem – what is the problem? 5. Meter out how to work on this – need to focus on the critical few, but end state is VPP+ 6. Understand how work is done – how is work really being executed, cited AIM disconnect 7. Visibility of levels 8. Higher standards versus minimum requirements 9. Adequate resources 10. Reach the contractors 11. Creacte a culture of openness 12. Ship’s force interface must be considered (they are not maintenance experts) 13. Margin to the pinnacle event 14. Interdependence (Route to Zero) Mr. Brice reviewed feedback received from the industrial activities in response to NAVSEA data calls. He presented the findings from the investigation of the fatality in USS RONALD REAGAN as a series of switches which lined up and resulted in the fatality [Soule – While the “switch theory” approach to understanding accident causality is instructive, it tends to be misleading because it is contaminated by the brilliance of hindsight – after the accident, having studied it in near infinite detail, it appears “obvious” what the errors were and observers are left wondering, “How could they have been so stupid?” In most cases, the parties involved were doing the best they could consistent with their training with the 11 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes knowledge they had at the time]. Studying Safety injuries is not the answer. It is better to Quality Engineering understand the switches that are closed. He reviewed four conclusions: (1) need more of a risk based approach focused on reducing hazards and potential for serious injuries; (2) need to find and fix safety problems instead of Worker Supervision them finding us; (3) we need a long range Training vision of zero injuries [Soule – this is of dubious value since human variability in attention and other cognitive processes make it exceedingly unlikely that everyone is always Figure 4. Work Model going to follow all procedures or that no equipment will ever fail to operate as designed]; and (4) need to embrace and adopt proven models – Nuclear Safety, Radiological Safety, Crane Safety, DuPont Route to Zero, High Reliability Organization theory, etc. Mr. Brice reviewed the Route to ZERO (Injuries) progression. He asked the group to characterize the average state in the Route to Zero progression in their organization. The group identified the public-sector shipyards as being largely Reactive (Natural Instincts) to Dependent (Supervision). The group identified the private sector new construction shipyards as being slightly more advanced than the publicsector shipyards (i.e., possibly Independent). They identified the private sector maintenance shipyards as being largely Reactive (Natural Instincts). The group reviewed the elements of the VPP+ model. The agenda for the remainder of the Safety Summit is based on working to achieve the VPP+ end state. The group discussed the leadership role of unions. Mr. Mueller said that the OSHE Offices (Code 106) are not viewing themselves as the regulator of safety. He asked the question, “What does it mean for Code 300 (Operations) and Code 900 (Resources) to own safety?” He reviewed the nuclear work model, comprised of Engineering, Supervision, and Training (Figure 4. Work Model). The group concluded that the production departments require more safety training to be able to own safety. The objective is to enable the production departments to engineer safety into work planning and to ask the OSHE Office if it is sufficient. The OSHE Office will tell the production departments what they think and walk away. Codes 105, 106, and 130 oversee production (Figure 4. Work Model). The group endorsed the Safety Pyramid, ALARA, and Route to ZERO concepts and the VPP+ model. Mainstreaming Safety should move everyone to the Interdependent state. RADCON Production Projects Level 1 and 2 Safety Problems (Ms. Gochenouer). Ms. Lyrita Gochenouer, PHNSY&IMF (Code 106) led a discussion to define criteria for Level 1 incidents and Level 2 problems, based on work completed by PHSNY&IMF to adapt SEA 08’s 17 criteria to ship repair and 12 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes maintenance work following the USS CHEYENNE arc flash incident. The group agreed on four high-risk areas (i.e., work that could immediately affect life or health): (1) Electrical Safety, (2) Fall Protection, (3) Confined Space Entry, and (4) Energy Control. The group agreed on the definition of Level 1 incidents as comprising events requiring Trouble Reports (sent outside the organization). The group agreed on the definition of Level 2 incidents as comprising events requiring a Critique (remaining inside the organization). Using the PHNSY&IMF list, Ms. Gochenouer led the group through a discussion of Level 1 criteria in the four high-risk areas, followed by a discussion of Level 2 criteria. The group produced a draft list of Level 1/2 Criteria. Ms. Gochenouer noted that PHNSY has conducted 10 times more critiques since implementing the new Level 1/2 criteria. Trouble Report Documentation (CAPT Soule). CAPT Soule (SUPSHIP NN) reviewed what he believes are best practices for improving the quality of Trouble Reports and Incident Reports. The purpose of the Trouble Report or Incident Report is to share information about an incident or problem and what an organization learned to do differently. He recommended answering seven questions: (1) What happened? (2) Why was it significant? (3) What principles were violated (i.e., key errors)? (4) Can I (or anyone else) use this incident for training? (5) What corrective actions were taken? (6) If we were to do it over again, what would we do differently? (7) Who is the point of contact (i.e., for more information concerning the incident)? CAPT Soule recommended listing key errors in chronological sequence, calling them out specifically in the text with a label like “Error One), and extending the chronology as far back in time as necessary to capture appropriate corrective actions. He recommended incorporating comments received/provided of Trouble Reports and Incident Reports in organizational self-assessments. CAPT Soule provided several example Trouble Reports and Incident Reports he wrote to illustrate his points. He recommended reading a newly published book, The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right by Atul Gawande, because it could help organizations produce checklists for writing better Trouble/Incident Reports. Refer to Enclosure (3) Bibliography. Capt Soule provided a suggested checklist for writing incident reports: Summary no more than one to two paragraphs. Three to four sentences would be ideal. Summary briefly explains What happened Problem clearly stated Why significant Key errors with a little context that ties to them to the problem Errors are called out in the chronology with enough text to make it clear what the error was, not merely “Error 1” (e.g., the operator failed to ..., personnel approved the procedure without adequte experience to identify the risk, etc.). Don't mince words about what was done wrong. Use clear, brief language (“the engineer failed” A junior employee, not involved in the incident, can read the summary and corrective actions and 13 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes explain what went wrong and why. They can also explain how it applies to the work they do. There is a brief explanation of each error, separate from the chronology, that shows how the errors tied to fundamental practices. There is a brief section that explains how the work would be done differently next time (this is where the real learning is demonstrated). Minimize use of passive voice (since it obscures who did what). A Point of Contact is identified for follow up. Wednesday, May 12, 2010 Case for Change (Mr. Brice). Mr. Brice opened the second day of the Safety Summit by reviewing the Case for Change: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Fatalities are unacceptable in the work we do Need hazard focus – understand and keep “switches” open Learn to “see” Our attitudes need to be “It is personal” Understand how work is actually done, not the way you imagine it should be done. The group revisited the Mainstreaming Safety topic, discussing the leadership role of the unions, the work model (and the shared ownership for safety by engineering and production), worker training, safety drills, reporting culture, customer support, and the overarching need for the right standards USS BATAAN Incident (Mr. Pristou). Mr. Walt Pristou, Norfolk Naval Shipyard (Code 106), briefly related news of an incident that occurred in USS BATAAN (LHD 5) the previous day, while undergoing repair and maintenance at BAE Systems Ship Repair in Norfolk, Virginia. Six non-BAE contractors were nearly overcome by carbon monoxide poisoning while conducting sandblasting operations. Several of the workers were treated for carbon monoxide poisoning in hyperbaric chambers at a Norfolk hospital. Details of the incident were still under investigation. The group noted that except for one or more open switches, this incident could have been the multiple fatality pinnacle event discussed the previous day. Engineering for Reduced Risk (Mr. Brice). Mr. Brice led a discussion on engineering for reduced risk. He reviewed the findings from the investigation of the fatality in USS RONALD REAGAN as a series of switches again. Investigations concluding that problems included ship’s force training and shipyard supervision and technical control were inadequate. The crew did not understand how NSTM 300 applied. The crew did not question doing work in an energized condition. The division prioritized maintenance efficiency over maintenance safety. The Work Authorization Form (WAF) was not 14 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes adequate, in that the shipyard did not clearly specify ship’s force and shipyard responsibilities. A shipyard electrician was the team leader, but he did not provide supervision to ship’s force personnel because he thought it was not his place to do so. The shipyard allowed work with no briefing and did not stop the work when a problem occurred. In conclusion, the shipyard is the maintenance expert and must provide technical control. Ship’s force and shipyard personnel must work to the same standards. The shipyard must examine who performs the work and evaluate their capability to do so safely. It is not right to assign energized work to ship’s force personnel because they have different requirements. The group discussed how the lessons learned from the USS RONALD REAGAN fatality apply across the board (i.e., new construction shipyards, MSMO shipyards, etc.). The group noted that the capability of ship’s force personnel to perform maintenance may have dropped significantly over the past ten years with the downsizing of the Ship Intermediate Maintenance Activities. However, in the case of the USS RONALD REAGAN fatality, the group noted that the mishap victim was nuclear-qualified and a skilled electrician. In the case of new construction or carrier Refueling Complex Overhauls (RCOHs), the SUPSHIP, as the Naval Supervising Authority (NSA), does not oversee ship’s force personnel or manage the work. The SUPSHIP is not the regulator for ship’s force; the Type Commander is. However, SUPSHIP personnel should not walk past a problem they recognize. Likewise, the Multi-Ship, Multi-Option (MSMO) ship repair contractors utilize the WAF process. The Port Engineer brokers availability work packages to the private-sector shipyard and to ship’s force. The private-sector shipyard provides no oversight of ship’s force in this circumstance. The group acknowledged that during an availability, the ship’s force does little that is not related to the availability. High Risk Work in Naval Reactors Field Activities (Mr. Weishar). The group returned to the discussion of controlling high-risk work. SEA 08 developed a permitting process for highrisk work (described previously by Mr. Mueller). The proposal is that SEA 04 adopt this practice. Mr. Tom Weishar (Naval Reactors) reviewed SEA 08’s High Risk Work Permit process. He distributed a copy of Section 6 (High Risk Work) from the Safety Requirements Manual (S9213-55-MAN-000/(U), ACN 1, May 2010. This chapter included the definition of high-risk work (Article 601 – High Risk Work) and the process to authorize high-risk work (Article 602 – Authorization to Perform High Risk Work). Focus is placed on assuring that managers are aware of planned high-risk work and authorize it, that the workers understand the risks before executing the work, and ultimately, that engineers develop appropriate controls to eliminate or minimize the risk. Another element is developing appropriate precautions in technical work documents (Article 603 – High Risk Work Controls in Formal Work Procedures) and specifying the knowledge requirements of engineers to write technical work documents (Article 604 – Knowledge Requirements for 15 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes Preparation of Formal Work Procedures with High Risk Work Controls). The High Risk Work Permit process has yielded a number of benefits in the five joint DON/DOE facilities supporting the U.S. Naval Nuclear Propulsion Program. Senior managers review high risk work for the coming week. Senior managers question why high risk work needs to be performed (e.g., work on energized components). The process drives managers and workers to think about the work and eliminate wasted risk. In response to questions from the group, Mr. Weishar noted that the facilities have limited work involving diving operations. The facilities rely on the diving program controls to assure safe diving operations. The facilities also have limited confined space entry work (i.e., less than 12 times at a year at all five facilities). High Risk Work in Ship Repair and Maintenance (Mr.MacGinnis). Mr. John MacGinnis, PNSY, led a discussion of how to apply SEA 08’s High Risk Work Permit process to the ship repair and maintenance business. He synopsized the group’s discussion: 1. Define high risk work items: a. SYs, RMCs, SUPSHIP Reps. b. Start with 08 List. c. Compare to NAVSEA / OSHA requirements. 2. Assess Current Processes: a. WAFs, Briefs, JHAs, etc. b. Define problems – lack of management visibility. c. Worker knowledge and commitment. 3. Recommend HRWP or how to integrate into existing process (WAF). 4. Recommend how to improve engineered controls for safety. 5. Fall protection, electrical safety, ER, Nuclear, Non-Nuclear. 6. Timeframe: 6-month project. Shipboard 1. WAF (JFFM) SY/SF (TUM) a. SY/SF 2. Tagouts 2-valve SY/SF/CO 3. Elec. Safety NSTM 300/Ch 230 4. Haz Evol (TS 099) SY/SF/LTE 5. Haz Evol (?) SY/SF/LTE 6. (ITPAM) Prerequisites (PRL) Briefings Dry Runs Readiness Reviews Table tops Mock-ups Training HRWP Management Oversight Direct Worker Participation TWD/FWP Formal Work Package Requirements Testing LTE 16 Facility LOTO – OSH Manual Dry Dock LOTO – MILSTD-1625 Comm Spec EM-385-1-1 NFPA-70E NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes 7. High Risk (6010) SY/SF/SSC 8. Radiography RASP) 9. Hot Work UIPI CFR Lifts P-307 10. Complex 11. (JFFM) SOS MIL SY/SF Figure 5. High Risk Work in Ship Repair and Maintenance The group discussed reviewing ship’s force personnel safety requirements, especially electrical safety requirements. Refer to Figure 5. High Risk Work in Ship Repair and Maintenance. The group discussed the High Risk Work Permit process in relationship to the Industrial Ship Safety Manual for Submarines, S9002-AK-CCM-010/6010 and the Ship Safety Council. The group discussed integrating the High Risk Work Permit process with the WAF process. Mr. Weishar said that the WAF would not accomplish the objective of the High Risk Work Permit process. The High Risk Work Permit asks the workers, engineers, and managers to be directly involved in planning the work and making it safer. The High Risk Work Permit includes an evaluation and decision to do the work in a specific way and to accept the risk. The High Risk Work Permit includes worker involvement and buy-in. The group discussed the process for authorizing and performing energized electrical work shipboard. In the current process, the ship’s Commanding Officer endorses accomplishing this high-risk work, but the Shipyard Commander does not participate in the process. The current process does not provide the second-level review asking, “Do we really have to do the work this way?” The current process provides a framework, but management oversight and direct worker participation may not be adequate. The group determined to form a working group to review the matter. PNSY agreed to lead the working group. The working group will address public-sector shipyard, ship repair and maintenance work as a starting point. This initiative will be expanded to private sector shipyards and facility repair and maintenance work later. The working group will determine if provisional measures should be put in place in the interim (e.g., electrical safety or fall protection). The working group will address changing behavior and culture. The working group will address specifying safety precautions in technical work documents. Risk Management and Worker Commitment to Safety (Mr. Wheeler). Mr. Ted Wheeler, PSNS&IMF (Code 900S), led a discussion of risk management practices and worker commitment to safety initiatives at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. He said that PSNS&IMF is revitalizing the Voluntary Protection Program initiative. He believes the shipyard has advanced beyond the Dependent stage of the Route to ZERO model. Workers recognize risk and do something about it, but the shipyard is not yet at the Interdependent stage. 17 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes - - - Response to Hazards and Mental Checklist. New employees receive 40 hours of indoctrination training, which is all inclusive, and then they are assigned to a work crew. Thereafter, they complete annual safety training through a computer-based training course. The annual safety training addresses workplace hazards. All other safety training is informal, conducted on the job. When do workers receive training in hazard recognition and control? Schedule is the priority. Developing a mental safety checklist without having the requisite knowledge and experience is problematic. PSNS&IMF has issued work readiness instructions. Code 950 workers and supervisors are conducting a dry run. The objective is to change the culture and encourage worker ownership for safety. The shipyard has rules in place, but the workers are not following the rules consistently. The work readiness instructions help workers to understand the work, safety and quality. The work readiness instructions provide a mechanism to take off schedule pressure (i.e., rushing to do a job). The group discussed how a supervisor of a multi-trade work crew provides job briefings to other trades. Supervisors ask workers to identify safety requirements and encourage interactive dialog. Also, supervisors understand the work packages well enough from experience to supervisor multi-trade crews. Operational Risk Management. PSNS&IMF has developed an Operational Risk Management Process Card. The worker must ask and answer three questions: (1) What’s going to hurt me (or those around me)? (2) What am I going to do about it? (3) If I can’t do anything, who do I tell? The worker writes concerns on the reverse side of the card and notifies the supervisor. The card forces the supervisor and employee to interact. PSNS&IMF is rolling out a High Hazard Checklist. PSNS&IMF is capturing Level 3 data in the Quality Performance System (QPS). The shipyard has added appropriate codes to QPS for tracking and trending. Prior to the recent SEA 08 audit, supervisors had to identify and report fall protection hazards (or other kinds of hazards) every day for a week. Active Participation in Safety Critiques. PSNS&IMF is training critique chairpersons to include safety in all of the critiques. Horizontal Enforcement of Safety Requirements. What makes a worker challenge a coworker to wear PPE? Workers do not challenge co-workers because there is no consequence for failing to do it. There should a consequence for not confronting a coworker about unsafe behavior. Does a twenty year old employee confront a fifty-five year old employee about unsafe behavior? PSNS&IMF is exploring ways to improve horizontal enforcement of safety requirements. PSNS&IMF has also undertaken initiatives to improve Personal Protective Equipment options and worker comfort while wearing PPE. The group commented that lack of comfort is not the reason workers do not wear PPE. 18 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes - - Behavior-Based Safety. Why do workers tolerate unsafe behavior in the workplace? It has to do with, “Let’s get it done!” Managers place the priority on schedule, along with cost and quality. What are the consequences of unsafe behavior? PSNS&IMF is exploring ways to improve safe behavior. Safety Observer. PSNS&IMF is exploring ways to utilize employee safety observers. The unions do not want employees reporting on other employees, leading to disciplinary action. Shops and codes need to accept the role of safety observer. Can the safety observer role be filled by Code 106 as part of the regulator role? Problems Ideas: 1. Workers not recognize hazards: 1. Improve training – OSHA 10 hr / 30 hr: a. Weak training. a. Safety training specific. b. Not surveilling. b. Skill – apprentice training. 2. Environment Poor: c. High-risk areas. a. Too many safety deficiencies. 2. Worker surveillances – employee-based. b. Management not correcting / standards. 3. Interactive briefs – worker led. c. No consequences. 4. Improve Environment! Fix Deficiencies. 3. Brief – one way/not interactive. 5. Management surveillances. 4. Critiques – need safety focus: 6. Union leadership too! d. Too much on employee error. 7. Recognition of good behavior and self5. Not backing each other up! reporting, reward / positive. 6. Too much emphasis on schedule / cost! 8. Safety Observer. 7. Resources? Figure 6 – Risk Management and Worker Commitment to Safety After lunch, the group developed a summary of problems and ideas from the risk management discussion (Figure 6 – Risk Management and Worker Commitment to Safety). The group discussed how well apprentice programs train workers in the safety requirements associated with the trades. Safety training varies from trade to trade. The group discussed the need for safety observers to function in a manner comparable to RADCON monitors. Some shipyards utilize safety observers for high-risk operations identified in the Industrial Ship Safety Manual for Submarines. To some of the participants, the concept of a designated safety observer runs counter to mainstreaming safety and giving ownership for safety to the worker. The group determined to assign four working groups, one from each shipyard to address one of the four high-risk areas, to address risk management and worker commitment to safety: 5. 6. 7. 8. PNSY (Code 950 2730/270), Electrical Safety. NNSY (Code 970 980/710), Fall Protection. PSNS&IMF (Code 920/250), Confined Space Entry. PHNSY&IMF (Code 960 2350/260), Energy Control/LOTO. 19 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes Safety Metrics (Ms. Hubby). Ms. Kim Hubby, PNSY (Code 106), led a discussion of safety performance metrics. She provided examples of how PNSY continually assesses the Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) Program through surveillance. The shipyards have surveillance checklists, but surveillances cannot be based on checklists alone. The checker must also observe what’s going on with the work and ask open-ended questions. All of the shipyards are conducting surveillances; however, none of the shipyards currently is performing effective trend analysis after the data are collected. Additionally, the group must define criteria for Level 1 through 4 events in order to collect data consistently at each level and implement the Safety Pyramid and ALARA concepts (i.e., a robust Level 3/4 surveillance program driving down Level 1/2 events). The group defined a set of safety metrics to report corporately. The group determined to continue to report OSHA TCIR and DART (lagging indicators) and to add reporting the number of Level 1 incidents and Level 2 problems. The group determined not to track injury-free days, as it might inhibit reporting. 1. Continue OSHA TCIR and DART: a. Report organization-level quarterly. b. Project level monthly. 2. Add Level 1 and 2 Problems – Number a. Report organization-level quarterly. b. Project level monthly. Improving Hazard Awareness and Abatement (Mr. Medrano). Mr. Jeffrey Medrano, NNSY (Code 106), led a discussion on improving hazard awareness and abatement. The focus is on collecting and analyzing Level 3 surveillance and inspection data to prevent Level 1 incidents and Level 2 problems from occurring. The Radiological Deficiency Report (RDR) system is a model for this approach. The shipyards currently employ various checklists, but not all of the checklists are aligned with the high-risk areas. In some cases, defined inspections are not being completed. No specific hazard recognition training is in place. Hazard recognition training is needed to increase the involvement of many people across the organization to identify deficiencies (i.e., learn to see). Reporting culture (i.e., self-reporting) is weak. Information systems currently in use include HDA and ODR for workplace deficiencies and QPS for surveillances. Some systems can track deficiencies from cradle to grave. Lots of data are collected, but analysis is performed at a high level only. As an example, PHNSY&IMF conducts 300 workplace inspections per quarter, identifying 600 to 700 deficiencies per quarter. The shipyards currently are not getting a lot of value from analyzing the data. Standard attributes for high risk areas are not defined to support meaningful analyses. The shipyards should know where they stand on a daily basis (i.e., better finding of deficiencies, better trending, and better fixing, plus more dynamic looks at behavior). The RMCs are using ESAMS to track workplace deficiencies from cradle to 20 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes grave. The RMCs are not conducting surveillances. The SUPSHIP organizations use a deficiency tracking system, called TSME, funded by PMS 400. The group determined to form a working group to improve hazard awareness and abatement, with a focus on finding and fixing Level 3 deficiencies before they become Level 1 incidents and Level 2 problems. This project will include a gap analysis of the RDR process. PSNS&IMF will lead the working group. Opportunities for improvement include: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Improve Safety Deficiency Reports (SDRs). Better focus on finding L3 hazards to prevent L1 and L2. Integrate safety issues associated with work. Standard Attributes (High Risk), align L3 with L1 and L2. Hazard Awareness and Training (“Learn to See”). Start with focus on High Risk. Consider the RDR process. Start with the four naval shipyards. RMCs participate. Self Assessments (Mr. Ueda). Mr. Herb Ueda, PNSY (Code 106) reviewed the OSH Program Assessment Process. This self assessment process is aligned with UIPI 0090-002 (SelfAssessment) and OPNAVINST 5100.23, Chapter 5 (Prevention and Control of Workplace Hazards). The self-assessment process is an ongoing, year-round process. Significant findings are elevated immediately. Data are reviewed at least monthly. Training is included in the self-assessment. Mr. Ueda reviewed programs currently being assessed. Mr. Ueda discussed issues with the self-assessment process. For example, it is difficult to get customers to accept action items from the self assessment and complete them. Briefing self assessment results in an appropriate management forum, such as the OSH Policy Council, helps to direct attention to correcting findings of the assessment. Mr. Kim Taylor, SEA 04RS, provided NAVSEA feedback concerning the shipyards’ self-assessment processes. He noted that recent SEA 08 and SEA 04 inspections identified significant issues that were not identified in the self-assessments. Self assessments must be performed under the OSHE Office lead, but with participation from other shipyard departments. Functional self assessments for safety are not just an OSHE Office responsibility, but a shipyard-wide responsibility. The standard for self assessments must come up. Self assessments must identify significant issues. The expectation is that the shipyards are finding problems in high-risk areas, addressing the problems, and preventing Level 1/2 events from occurring. Mr. Taylor briefed the group on a Chief of Naval Operations message CNO 121425Z FEB10 (Subj: SECNAV / SECDEF Reduction Goal). This message requires field activities to identify the top-five safety concerns, along with safety program deficiencies, weaknesses, successes, and roadblocks to successful mishap prevention efforts. The first assessment under this new guidance is due to NAVSEA by March 1, 2011, for Calendar Year 2010. 21 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes Safety Summit Wrap-Up (Mr. Brice). Mr. Brice led a wrap-up of the Safety Summit. The group briefly returned to the criteria for Level 1 and 2 events. Rather than attempt to complete the list in the time remaining, Mr. Brice said that SEA 04R, the shipyard OSHE Offices, the RMCs, and the SUPSHIP organizations would take the lead with other codes to complete the list during the following week. This working group will align the accident/injury language in several of the criteria with the Navy’s Class A and B language. The plan then is to update the Trouble Report instruction with the Level 1 criteria and the Critique UIPI with the Level 2 criteria. Members of the group questioned why a Trouble Report and critique are required in the case of a fatality when a SIR is required. The Trouble Report and critique need to be completed to distribute the lessons learned from the incident quickly. The SIR necessarily takes time to complete. Mary Anne Zivnuska (SEA 00L) said that she would contact the Naval Safety Center to discuss NAVSEA’s intention to complete a Trouble Report and a critique for a fatality in advance of the SIR. Finally, the group discussed the idea to develop a ship repair and maintenance safety manual, patterned after SEA 08’s safety manual for the joint DON/DOE facilities. An advantage of such a safety manual is that it could be invoked in ship repair and maintenance contracts. Thursday, May 13, 2010 Safety Summit Out-Brief Preparations (Mr. Brice). Mr. Brice led the group through a review of the draft out-brief presentation to RADM Campbell. The group recommended minor edits to individual slides in the PowerPoint presentation. The group discussed two issues that require follow-up after the meeting. The first issue concerns the ability of NAVSEA to provide input to the Joint Fleet Maintenance Manual (JFFM) since it is not a NAVSEA document. SEA 04R will follow up with the fleet concerning how NAVSEA can provide input to the JFFM. The second issue concerns addressing ship’s force unsafe practices occurring in shipyards that have nothing to do with the ship’s availability. SEA 04R will follow up with the fleet and the Naval Safety Center concerning addressing ship’s force unsafe practices not related to a ship availability. Safety Summit Out-Brief (RADM Campbell). CDR Gelker, assisted by designated members of the group, briefed RADM Campbell and Mr. Mueller on the results of the Safety Summit meeting using a PowerPoint presentation *(reference outbrief presentation). Concerning the review of the USS RONALD REAGAN fatality, RADM Campbell asked how the corporation will assure that the shipyards and ship’s force personnel will work to the same standards. He questioned whether it is clear who should be doing work on energized equipment. He asked who will review the decision to work energized before taking the work package to the shipyard’s Project Superintendent and ship’s Commanding Officer. A change 22 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit May 11 – 13, 2010 Meeting Minutes is required, and the working group for High Risk Work must address this issue, including determining the need for interim controls. Concerning the Trouble Report for the USS BATAAN incident, RADM Campbell asked if this Trouble Report was distributed to everyone in the group. There may be a problem with distribution of the reports to SUPSHIP organizations. Mr. Paul Mieszczanski (SEA 04XQ) will make sure the SUPSHIP organizations are on the distribution list. Mr. Mueller noted that the Headquarters regulator has to concur with three parts of the Trouble Report. Trouble reports must be evaluated. Approximately 25% of nuclear-related Trouble Reports are rejected. Concerning Engineering for Reduced Risk, Mr Mueller asked who decides how high-risk work items are accomplished. His view is the answer should be that Engineering decides. In the Work Model (Figure 4), Engineering is on top because Engineering they drive the technical control of the work we do. The shipyard’s Project Superintendent and ship’s Commanding Officer can approve, but Engineering decides. Concerning Risk Management and Worker Commitment, Mr. Mueller asked why the supervisor is not being held accountable for a worker committing an unsafe act. Concerning Self Assessments, Mr. Mueller asked how the SUPSHIP organizations and the RMCs perform self assessments. The SUPSHIP organizations’ self assessment process is not as in-depth as the shipyards’ process. The RMC’s use ESAMS to conduct self assessment. Mr. Mueller said that it was a mistake to focus on process first. Focus on people, their training, and their capability to do the work first. People who do not think with good engineering discipline write bad self assessments. Concerning the Plan of Action and Milestones, RADM Campbell asked if a strategic communication plan is required to help the workforce understand these safety initiatives. The group must determine how to explain the initiatives to the workforce. Finally, several members of the group expressed concern for resources to address these initiatives and current workload. Mr. Mueller said that the shipyards, RMCs, and SUPSHIP organizations are not being asked to do extra work. The two fatalities we have had this year indicate that they are already not meeting the requirements. RADM Campbell asked if the group understands what the problem is yet. He asked the group to consider if what the corporation is doing with safety will enable or inhibit the core business. If it enables the core business, then resources will take care of themselves. If it inhibits the core business, then additional resources will be required. RADM Campbell thanked the members of the group for their efforts. The meeting adjourned. 23 NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit Agenda 1. Date: 11-13 May 2010 2. Time: 0800 – 1700 (T&W) and 0800-1200 (Th) 3. Location: 1100 New Jersey Ave, Washington DC 20003 Room: 850 4. Participants: SUPSHIP, RMC and Shipyard Code 106/ESH Managers NSY Code 300 and 900 Other SUPSHIP/RMC Reps 5. Purpose: To improve safety across the NAVSEA Industrial Activities and drive safety hazards and mishaps to “As Low as Reasonable Achievable” 6. Objectives: a. Achieve alignment on Case for Change to raise standards, drive injuries to zero, and significantly reduce risks for serious mishaps. b. Mainstream safety into the entire organization where work is engineered for reduced risk, all hazards are reduced to ALARA, and workers mature from compliance mode to commitment with interdependency (backup). c. Develop Safety Pyramid and VPP+ model to achieve these objectives. Specific deliverables are as follows: (1) Definition of Level 1 and Level 2 safety problems. (2) Update guidance to require Critiques and Trouble Reports for these problems. (3) Develop guidance for High Risk Work Permit program. (4) Operational Risk Management (ORM) by workers in execution of work. (5) Update metrics for projects/availabilities in addition to current metrics. (6) Update Training programs for high risk programs to require practicals, annual refreshers, and level of knowledge examinations. (7) Develop new guidance for surveillances and standardize documentation in Safety Deficiency Reports (SDRs). (8) Develop action to improve self-assessments. 7. Agenda: Tuesday, 11 May 2010 1 Enclosure (1) NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit Agenda 0800-0900 Introduction & Welcome (SEA 04R – Jim Brice) • Summit Goals & Objectives • Around the Room Expectations 0900-1000 Safety at Naval Reactors Facilities (SEA 08R – Troy Mueller) • Fundamentals of Safety • Mainstreaming Safety • ALARA and Dupont Road to Zero • Risk Approach – Switch Theory • Safety Ownership – Total Workforce 1000-1015 Break 1015-1100 Safety at Naval Reactors Facilities (SEA 08R – Troy Mueller) – continued 1100-1200 NAVSEA Leadership Perspective (SEA 00 – VADM McCoy) • Interactive Session • Participants be prepared to discuss biggest challenges in achieving a step improvement in safety. 1200-1230 Lunch 1230-1400 Mainstreaming Safety (SEA 04R – Jim Brice) • Case for Change - Alignment • Review of Assessment Findings • VPP+ • Safety Ownership – 106 Role 1400-1530 Definition of Level 1 and Level 2 Safety Problems (Pearl Harbor NSY – Lyrita Gochenouer) • Objectives • Break • Breakout Sessions to define Level 1 & 2 Problems 1530-1630 Level 1/2 Problem Group Discussion and Way Ahead (Pearl Harbor NSY – Lyrita Gochenouer) 1630-1700 Improving Trouble Report Documentation (CO, SUPSHIP NNS - CAPT Soule) 2 Enclosure (1) NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit Agenda Wednesday, 12 May 2010 0800-0945 Engineering for Reduced Risk (SEA 04R – Jim Brice, SEA 08R – Tom Weishar, Portsmouth NSY - Rep) • Technical Control Procedures and Processes • Interactions with Ship’s Force • Control/Coordination of Contractors • Use of High Risk Work Permits 0945-1000 Break 1000-1100 Risk Management and Worker Commitment to Safety (Puget Sound NSY – Ted Wheeler) • Response to Hazards and Mental Checklists • Active Participation in Critiques • Horizontal Enforcement • Behavior-based Safety • Safety Observer • Follow-on Discussion in 300/900 Meeting 1100-1200 Safety Metrics (Portsmouth NSY – Kim Hubby) • Leading Indicators • Organization and Availability Metrics 1200-1300 Lunch - (Code 300 and 900 dismissed for their meeting) 1300-1445 Improving Hazard Awareness & Abatement (Norfolk NSY – Jeff Medrano) • Surveillances & SDR Process • Data Collection and Analysis • How do I improve to Mirror RDR Process? 1445-1500 Break 1500-1600 Safety Training Lessons Learned (SEA 04RS – CDR Gelker) • Review of Assessments • High Voltage Electrical • Fall Protection Trainer • OSHA 10-hour and 30-hour course • Supervisor and Risk Management 3 Enclosure (1) NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit Agenda 1600-1700 Self-Assessments (SEA 04RS – Kim Taylor, Portsmouth NSY – Herb Ueda) Thursday, 13 May 2010 0800-0930 Electrical Safety – Feedback on Effectiveness of Improvement Actions (SERMC – Joey Cartwright) • Deep Dive Responses • (Entire Group Reconvene and discuss) 0930-1000 Finalize products and POA&M 1000-1200 Group Presentation/Question and Answer with SEA 04 and 04B 8. Agreements: TBD 9. Action Items: TBD Notes: Refreshments including lunch will be provided on Tuesday and Wednesday for a refreshment fee of $25. Morning refreshments will also be provided on Thursday. VTC capabilities are not available for this meeting. Will be computer, projector, and screen. Checking webinar capabilities. 4 Enclosure (1) NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit Attendance Roster Name Stewart Adams Chuck Almond Rich Anderson Marc Baillargeon Andrew Blanco Larry Blevins Geno Borelli Marc Boutin Jim Brice CAPT Mark Bridenstine Tim Brorson Roger Brown Luis Campos Joey Cartwright Russell Chantry Leslie Cole Darrilyn Cranney Robert Fogel Frank Dodderer Bill Docalovich CDR Garrett Farman Tony Frey CDR Jennifer Gelker Lyrita Gochenouer CAPT William Greene Jose Gutierrez James Holdman Kim Hubby Tim Hughes Michael Tim Jacks Penny Jones Troy Kaichen David Kopack CAPT Dean Krestos Jeff Lawrence Rich Luke John MacGinnis Rick Marvin Jeffrey Medrano Activity NAVSEA 04RE NAVSAFECEN PHNSY&IMF PNSY SEA 04RS NNSY SUPSHIP BA PNSY NAVSEA 04R NNSY PSNS&IMF PSNS&IMF SWRMC SERMC NNSY PSNS&IMF ODASN (Safety) PHNSY&IMF SERMC NGSB Newport News SRF-JRMC PSNS&IMF NAVSEA 04RS PHNSY&IMF PSNS&IMF SEA 04Y SWRMC PNSY SUPSHIP GC NNSY PSNS&IMF PNSY SEA 04RE SUPSHIP BA SERMC 2A2 NAVSEA PNSY PNSY Naval Reactors NNSY 1 E-Mail Address stewart.d.adams@navy.mil charles.almond@navy.mil richard.w.anderson@navy.mil marc.baillargeon@navy.mil andrew.blanco@navy.mil larry.d.blevins@navy.mil eugene.borelli@supshipba.navy.mil marc.boutin@navy.mil james.brice@navy.mil mark.bridenstine@navy.mil timothy.brorson@navy.mil alvah.brown@navy.mil luis.c.campos@navy.mil joey.c.cartwright@navy.mil russell.chantry@navy.mil leslie.cole@navy.mil darrilyn.cranney@navy.mil robert.fogel.@navy.mil francis.dodderer@navy.mil bill.docalovich@ngc.com garrett.farman@srf.navy.mil anthony.frey2@navy.mil jennifer.gelker@navy.mil lyrita.gochenouer@navy.mil william.c.greene@navy.mil jose.i.gutierrez@navy.mil james.holdman@navy.mil kimberly.hubby@navy.mil timothy.hughes@supshipgc.navy.mil michael.jacks@navy.mi penny.jones@navy.mil troy.kaichen@navy.mil david.kopack@navy.mil jeffrey.m.lawrence@navy.mil richard.luke@navy.mil john.a.macginnis@navy.mil richard.d.marvin@navy.mil jeffrey.medrano@navy.mil Enclosure (2) NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit Attendance Roster Name Bill Miller Mike Monju Aaron Moore Troy Mueller Don Noyes Raphael Okimoto-Rive Steve Perkins Jerry Phillips Walt Pristou Bill Qualls Andres Quinones Andrew Ramsey Michael Rice Dennis Rickabaugh Anthony Ruiz Nick Smith Jenifer Solomon CAPT Ralph Soule Sheril Sprague Kim Taylor Gerald Thomas Randy Toole Benjamin Toyama Herb Ueda Ted Wheeler Thomas Weishar Bob Wright Mary Anne Zivnuska Activity SUPSHIP GR SUPSHIP GC SERMC Naval Reactors NAVSEA 04RS PHNSY&IMF NAVSEA 04XR SUPSHIP NN NNSY CACI SWRMC SUPSHIP GR NNSY PSNS&IMF SWRMC NNSY NGSB Newport News SUPSHIP NN PNSY NAVSEA 04RS PNSY PNSY PHNSY&IMF PNSY PSNS&IMF Naval Reactors SERMC NAVSEA 00L 2 E-Mail Address william.miller@supshipgr.navy.mil michael.monju@supshipgc.navy.mil aaron.e.moore@navy.mil troy.mueller@navy.mil don.noyes@navy.mil raphael.okimoto-rive@navy.mil steven.perkins@navy.mil jerry.phillips@supshipnn.navy.mil walter.pristou@navy.mil bqualls@caci.com andres.quinones@navy.mil andrew.ramsey@supshipgr.navy.mil michael.a.rice1@navy.mil dennis.rickabaugh@navy.mil anthony.ruiz1@navy.mil nick.a.smith@navy.mil jl.solomon@ngc.com ralph.soule@supshipnn.navy.mil sheril.sprague@navy.mil david.taylor8@navy.mil gerald.l.thomas3@navy.mil randy.toole@navy.mil benjamin.toyama@navy.mil herbert.ueda@navy.mil theodore.wheeler@navy.mil thomas.weisher@navy.mil robert.j.wright@navy.mil mary.zivnuska@navy.mil Enclosure (2) NAVSEA Industrial Activity Safety Summit Bibliography Dekker, Sidney. Just Culture: Balancing Safety and Accountability. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2007. Dekker, Sidney. The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2006. Gawande, Atul. The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books, 2009. Reason, James T. and Alan Hobbs. Managing Maintenance Error: A Practical Guide. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2003. Senge, Peter M. The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of The Learning Organization. New York, NY: Currency Doubleday, 2006. Weick, Karl and Sutcliff, Kathleen. Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty. Jossey-Bass; 2 edition, 2007. 1 Enclosure (3)