Table of Contents - Supreme Court

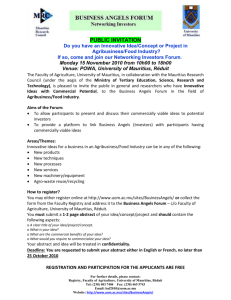

advertisement