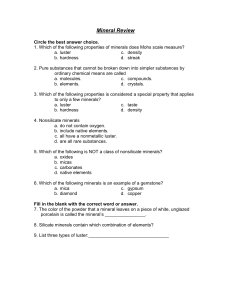

2010_MohsScale

advertisement

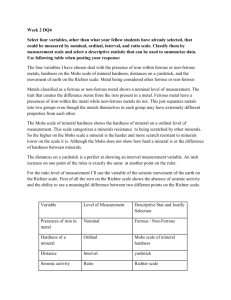

The Mohs scale was devised by Friedrich Mohs in 1812 (and therefore it's never spelled "Moh's"). You use the Mohs scale by testing your unknown mineral against one of these standard minerals. Whichever one scratches the other is harder, and if both scratch each other they are both the same hardness. The Scale ranges from 1 (softest) to 10 (Hardest) The Mohs scale is strictly a relative scale, but that's all that anyone needs. In terms of absolute hardness, diamond (hardness 10) actually is 4 times harder than corundum (hardness 9) and 6 times harder than topaz (hardness 8). Because it isn't made for that kind of precision, the Mohs scale uses half-numbers for in-between hardnesses. For instance, dolomite, which scratches calcite but not fluorite, has a Mohs hardness of 3½ or 3.5. There are a few handy objects that also fit in the Mohs scale. Fingernail: 2.5 Penny (actually any current US coin): about 3 (just under) Glass: 5.5 Good steel file: 6.5 Garnet paper: 7.5 Sandpaper (artificial corundum): 9 Mohs hardness is just one aspect of identifying minerals. Along with Mohs hardness, you need to consider luster, cleavage, crystalline form, color, and rock type to zero in on an exact identification. Minerals and hardness scale: Talc: 1 Gypsum: 2 Calcite: 3 Fluorite: 4 Apatite: 5 Feldspar: 6 Quartz: 7 Topaz: 8 Corundum: 9 Diamond: 10 Talc: Hardness 1 Talc is Mg3Si4O10(OH)2, always found in metamorphic settings. Talc is the softest mineral, the standard for hardness grade 1 in the Mohs scale. Your fingernail will easily scratch it. Talc has a greasy feel and a translucent, soapy look. Talc is very useful, and not just because it can be ground into talcum powder—it's a common filler in paints, rubber and plastics too. Other less precise names for talc are steatite or soapstone, but those are rocks containing impure talc rather than the pure mineral. Gypsum: Hardness 2 Gypsum is a soft mineral, hydrous calcium sulfate or CaSO4·2H2O. Gypsum is the standard for hardness degree 2 on the Mohs mineral hardness scale. (more below) Photo (c) 2009 Andrew Alden, licensed to About.com Your fingernail will scratch this clear, white to gold or brown mineral— that's the simplest way to identify gypsum. It's the most common sulfate mineral. Gypsum forms where seawater grows concentrated from evaporation, and it's associated with rock salt and anhydrite in evaporite rocks. Gypsum also occurs in a massive form called alabaster, a silky mass of thin crystals called satin spar, and in clear crystals called selenite. CALCITE: Hardness 3 Calcite, CaCO3, is the foremost of the carbonate minerals. It makes up most limestone and occurs in many other settings. FLUORITE: Hardness 4 Fluorite, calcium fluoride or CaF2, belongs to the halide mineral group. Fluorite isn't the most common halide—common salt or halite takes that title—but you'll find it in every rockhound's collection. Fluorite (be careful not to spell it "flourite") forms at shallow depths and relatively cool conditions where deep fluorine-bearing fluids, like the last juices of plutonic intrusions or the strong brines that deposit ores, invade sedimentary rocks with lots of calcium, like limestone. Thus fluorite is not an evaporite mineral. Mineral collectors prize fluorite for its very wide range of colors, but it's best known for purple. It also often shows different fluorescent colors under ultraviolet light. And some fluorite specimens display thermoluminescence, emitting light as they are heated. APATITE: Hardness 5 Apatite (Ca5(PO4)3F) is a key part of the phosphorus cycle. It is widespread but uncommon in igneous and metamorphic rocks. Apatite is a family of minerals centered around fluorapatite, or calcium phosphate with a bit of fluorine, with the formula Ca5(PO4)3F. Apatite also makes up sedimentary beds of phosphate rock. There it is a white or brownish earthy mass, and the mineral must be detected by chemical tests. FELDSPARS: Hardness 6 Feldspars are a group of closely related silicate minerals that together make up the majority of the Earth's crust. The compositions of the various feldspars all blend together smoothly. If the feldspars can be considered a single, variable mineral, then feldspar is the most common mineral on Earth. QUARTZ: Hardness 7 Quartz (SiO2) is a silicate mineral and the most common mineral of the continental crust. Quartz occurs as clear or cloudy crystals in a range of colors. It's also found as massive veins in igneous and metamorphic rocks. This double-ended crystal is known as a Herkimer diamond, after its occurrence in a limestone in Herkimer County, New York. TOPAZ: Hardness 8 Topaz, Al2SiO4(F,OH)2 Topaz is the hardest silicate mineral, along with beryl. It is usually found in high-temperature tin-bearing veins, in granites, in gas pockets in rhyolite, and in pegmatites. Topaz is tough enough to endure the pounding of streams, where topaz pebbles can occasionally be found. Its hardness, clarity, and beauty make topaz a popular gemstone, and its well-formed crystals make topaz a favorite of mineral collectors. Most pink topazes, especially in jewelry, are heated to create that color. CORUNDUM: Hardness 9 Corundum is aluminum oxide, the natural form of alumina (Al2O3). It is extremely hard, second only to diamond. Pure corundum is a clear mineral. Various impurities give it brown, yellow, red, blue and violet colors. In gem-quality stones, all of these except for red are called sapphire. Red corundum is called ruby. That's why you cannot buy a red sapphire! Corundum, in the form of industrial alumina, is an important commodity. Alumina grit is the working ingredient of sandpaper, and sapphire plates and rods are used in many high-tech applications. However, all of these uses, as well as most corundum jewelry, employ manufactured rather than natural corundum today. DIAMOND: Hardness 10 Diamond is a form of native carbon, the element C, in which the carbon atoms are stacked in a rigid three-dimensional framework. Diamonds form at great depth, well below the crust. Normal geologic processes bring diamonds to the surface too slowly to avoid retrograde metamorphism, which turns diamonds into graphite. They're able to reach the surface only in peculiar eruptions that explode into the air, leaving behind bottomless pipes of mantle rocks called kimberlites. Diamonds occur in a range of forms, from nearly perfect crystals to rough grains like this one to warty black lumps known as bort. All forms of diamond are valuable, either as gems or as superhard grinding and cutting grit. Gem diamonds are used for their hardness and transparency in the diamond anvil cell, an apparatus that puts mineral samples under high pressures and temperatures. (These pages come from About.com)