Paul Nash - Istituto Pascal RE

advertisement

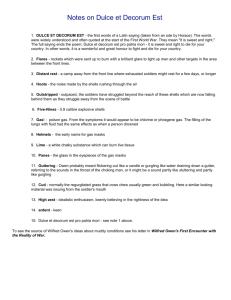

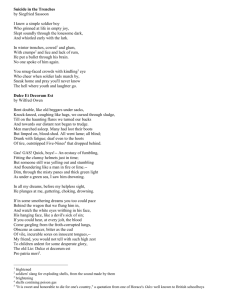

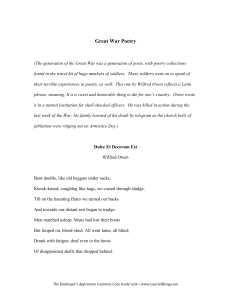

WAR POETS Textbook: pages 299 (historical background), 306-307 (Paul Nash), 317 (the War Poets), 382 (Wilfred Owen) MEDITATIO (1915) – Ezra Pound(1885-1992) When I carefully consider the curious habits of dogs I am compelled to conclude That man is the superior animal. When I consider the curious habits of man I confess, my friend, I am puzzled. THE SOLDIER (1915) – Rupert Brooke (1887-1915) If I should die, think only this of me: That there's some corner of a foreign field That is for ever England. There shall be In that rich earth a richer dust concealed; A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware, Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam, A body of England's, breathing English air, Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home. SUICIDE IN TRENCHES (1918) – Sigfried Sassoon (1886-1967) I KNEW a simple soldier boy Who grinned at life in empty joy, Slept soundly through the lonesome dark, And whistled early with the lark. 5 In winter trenches, cowed and glum, With crumps and lice and lack of rum, He put a bullet through his brain. No one spoke of him again. . . . . You smug-faced crowds with kindling eye Who cheer when soldier lads march by, Sneak home and pray you’ll never know The hell where youth and laughter go. 10 Dulce Et Decorum Est – Wilfred Owen (1883-1918) Bent double, like old beggars under sacks, Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge, Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs And towards our distant rest began to trudge. Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots 5 But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind; Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots Of disappointed shells that dropped behind. GAS! Gas! Quick, boys!-- An ecstasy of fumbling, Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time; But someone still was yelling out and stumbling And floundering like a man in fire or lime.-Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light As under a green sea, I saw him drowning. In all my dreams, before my helpless sight, He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning. If in some smothering dreams you too could pace Behind the wagon that we flung him in, And watch the white eyes writhing in his face, His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin; If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs, Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,-My friend, you would not tell with such high zest To children ardent for some desperate glory, The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est Pro patria mori. 10 15 20 25 FURTHER READING 1) November 9, 2003 Editorial Observer What World War I’s Greatest Poet Would Say About Hiding Our War Dead By ADAM COHEN When World War I broke out, the English saw going off to battle as a fine thing to do. They embraced the Latin poet Horace's dictum, "Dulce et decorum est, pro patria mori" — It is sweet and proper to die for one's country. But four years later, that romantic notion had been shattered by the grim reality of the mustard-gas-laced killing fields, and by the bitter words of Wilfred Owen, a British officer now recognized as the greatest poet of the Great War. Owen reported from the battlefields of France that, contrary to the prettified accounts being served up, the war he witnessed was full of blood "gargling" up from "froth-corrupted lungs" and "vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues." Owen's subject was, he declared, "war, and the pity of war." He expressed it through dark word portraits, in which dead and dying young men were stripped of any glory or sentimentality. Owen himself became one of these inglorious casualties when he was killed in action at the age of 25, just days before the war's end, 85 years ago this week. A revered figure in England, Owen found a large American following during the Vietnam War. He is often portrayed as antiwar, which he was not. What he stood for was seeing war clearly, which makes him especially relevant today. The Bush administration has been loudly attacking the news media for misreporting the Iraq conflict by leaving out good news. Owen would counter — in vivid, gripping images — that it is the White House, with its campaign to hide casualties from view, that is dangerously distorting reality. Owen was born in western England, near the Welsh border, to a middle-class family. When the clouds of war were gathering, he was embarking on a literary life. Like many young British men, he was caught up in war fever. As Dominic Hibberd, a leading Owen scholar, relates in a recent biography, Owen reacted to the German threat by writing a poem in which he approvingly cited Horace's dictum, adding that it was "sweeter still" to die in war "with brothers." He wrote to his mother, "I now do most intensely want to fight." Owen got his wish. He volunteered for the army in the fall of 1915, and was sent to France. Being there gave him a "fine heroic feeling," he wrote his mother a few months later. But before long, Owen was nearly killed by a German sniper. Then, while stumbling in the dark, he fell into a 15foot pit and ended up with a concussion. "I have suffered seventh hell," he wrote his mother. A large shell exploded near his head weeks later, throwing him into the air, and another, ghoulishly, exhumed a comrade, depositing his corpse nearby. Owen was haunted by blood-soaked dreams and, after a diagnosis of shell shock, he was committed to a war hospital. He befriended a fellow patient, the poet Siegfried Sassoon, and embarked on his most prolific period of writing. For Owen, the romance of war was by now long gone. He wrote of one wounded soldier, "heavy like meat/And none of us could kick him to his feet." While convalescing, Owen wrote his greatest work, "Dulce et Decorum Est," in which he provided a biting new take on Horace's assessment of death in battle. The poem is an account of a gas attack, and of one soldier too slow to put on his "clumsy helmet" who ends up "guttering, choking, drowning." Owen concludes by caustically telling the reader that if he had been there, "you would not tell with such high zest/To children ardent for some desperate glory/ The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est/Pro patria mori." When he recovered, Owen was sent back to France to fight. Ordered to lead his troops across a canal into heavy enemy machine gun and mortar fire, he was killed in the crossing. His mother received a telegram reporting his death on Nov. 11, 1918, the day the war officially ended. Owen, who was commended posthumously for inflicting "considerable losses on the enemy," was no pacifist. He told his mother he had a dual mission: to lead his men "as well as an officer can" but also to watch their "sufferings that I may speak of them." Owen was right that an honorable approach to war requires both ably leading troops on the battlefield, and reporting honestly what occurs there. The Bush administration, however, is resisting this honorable approach. In its eagerness to convince the public that things are going well in Iraq, it is leading troops into battle, while trying its best to obscure what happens to them. President Bush is not attending soldier funerals, as previous presidents have, avoiding a television image that could sow doubts in viewers' minds. He avoids mentioning the American dead — and the injured, who are seven times as numerous. The Pentagon has sent out emphatic reminders that television and photographic coverage is not allowed of coffins returning to Dover Air Force Base. There are already signs of public unease. Representative George Nethercutt, a Republican running for the Senate in Washington, was criticized last month for saying the media were focusing on "losing a couple of soldiers every day" rather than the "better and more important" story of progress in Iraq. (Mr. Nethercutt later complained that some accounts left out that he said losing the soldiers "heaven forbid, is awful.") But Mr. Nethercutt's was just the sort of bland formulation that would have driven Owen wild. Americans are already considering the relative merits of staying the course in Iraq, putting in an international peacekeeping force, and even pulling out. It is a somber debate, with great consequences for this nation, and the world. We must enter into it with full information, without lapsing into what Owen trenchantly called "the old lie" — or new ones. 2) Paul Nash Paul Nash (1889-1946), the British landscape painter and wood engraver, was born in London on 11 May 1889, the son of a lawyer. Nash was educated at St. Paul's School and then Slade School of art (unlike his younger brother John, who became an artist without formal training). Nash's first one-man exhibition was shown in his final year at Slade, 1912. With a style said to be influenced variously by Cézanne and Blake, Nash's watercolours were nevertheless highly distinctive. During the First World War Nash enlisted in the Artists' Rifles in 1914, serving at Ypres on the Western Front. Nash continued to sketch in an unofficial capacity during this time, specialising in scenes of trench life. By 1916 Nash had reached the rank of lieutenant in the Hampshire Regiment. Invalided home in 1917 as a consequence of a non-military accident, Nash's artistic skills were put to use with his appointment as an official war artist following an exhibition of worked-up paintings of his earlier war sketches. His stark landscapes of the Western Front created a lasting impression; his paintings continue to be displayed today as representative of the reality of war, although Nash himself complained during the war of the restrictions placed upon his work by the requirements of the War Propaganda Bureau (WPB) managed by Charles Masterman. The primary work of the WPB was to represent the government's view in the form of pamphlets, articles, books, film - and in paintings. By the close of the war the WPB employed the services of more than 90 artists in this capacity. From 1928 onwards Nash was increasingly influenced by surrealism and abstract art, a potent combination with his stark landscapes. He also worked as an illustrator and designer. Employed once again as a war artist in 1940 during the Second World War, Nash chose this time to depict the air war. Paul Nash died in Boscombe, Hampshire on 11 July 1946. His collected writings were published posthumously in a single volume in 1949. 3) MEMENTO (1944) - (Stephen Spender) Remember the blackness of that flash Tarring the bones with a thin varnish Belsen Theresenstadt Buchenwald where Faces were a clenched despair Knocking at the bird-song-fretted air. Their eyes sunk jelled in their holes Were held up to the sun like begging bowls Their hands like rakes with finger-nalls of rust Scratched for a little kidness from the dust. To many, in its beak, no dove brought answer.