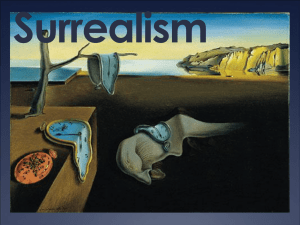

Surrealism jeudi 13 mars 2008 10:42 The Origins of Surrealist Art

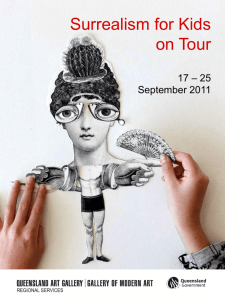

advertisement