September 26, 2003

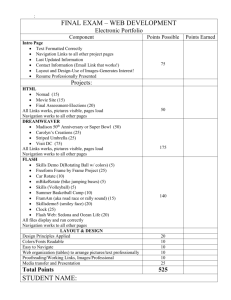

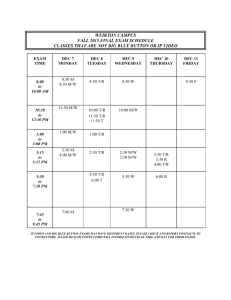

advertisement